America's former Greatest Intellectual takes a risk

Some centrist Jewish intellectuals with complex but supportive ideas about Israel might finally notice Ta-Nehisi Coates isn't all that bright.

From Longreads:

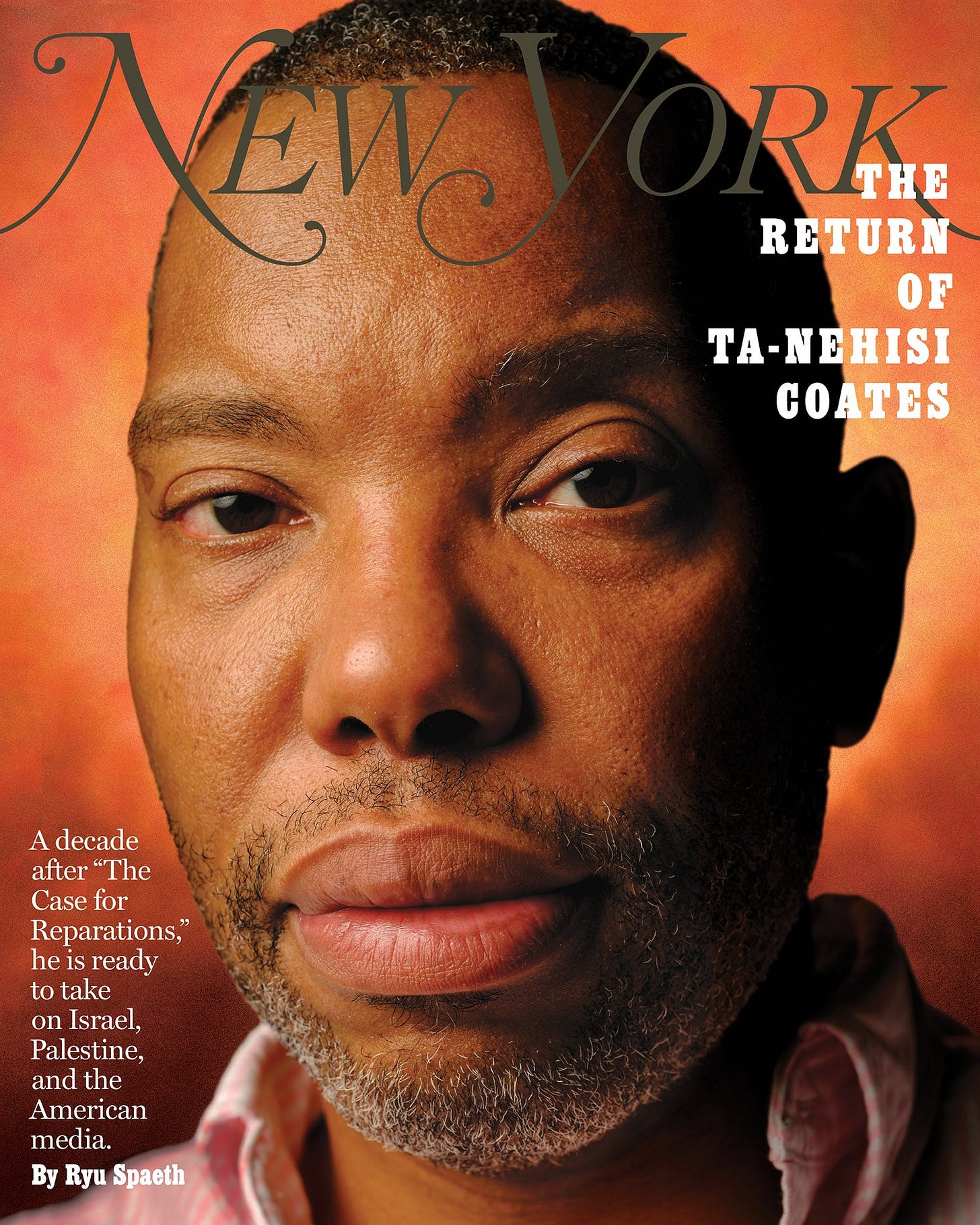

The Return of Ta-Nehisi Coates

Ryu Spaeth | New York | September 23, 2024 | 7,165 words

by Seyward Darby

September 23, 2024

Once among the most prolific political and social commentators in the US, Ta-Nehisi Coates has been relatively quiet for the last decade. (Emphasis on the relatively: Coates has written a best-selling novel and several comic books; guest-edited an issue of Vanity Fair about race, violence, and protest; and dipped his toe into screenwriting.) Next week, he’s turning up the volume once again with the release of his new book, The Message.

According to the publisher’s description, Coates’s book “is about the urgent need to untangle ourselves from the destructive myths that shape our world—and our own souls—and embrace the liberating power of even the most difficult truths.” Central among those truths is Israel’s violent, decades-long subjugation of Palestinians, and US institutions’ complicity in sustaining what Coates sees as a system akin to the Jim Crow South. As Ryu Spaeth explains in this wise, probing profile, many of those same institutions have championed Coates, which positions The Message as a professional risk. But Coates is more concerned with morality than he is with power, something that far too few people in media can rightfully claim to be:

In August, at the exuberant apex of Kamala Harris’s campaign for the presidency, Coates attended the Democratic National Convention in Chicago as a reporter for Vanity Fair. He was impressed by the diversity of the speakers. “We’re dying, having a ball,” he said of his friends on the group chat. “And Steve Kerr comes up and somebody’s like, ‘Oh, this convention is so Black they had to get a basketball coach to be the white dude!’” He went on, “Everybody’s getting a chance,” referring to the Native Americans and Latino Americans and Jewish Americans and gay Americans who stood up to speak. “I mean, everybody’s there, right?” But by the end of the first day, he learned that the Uncommitted movement, named after people who voted “uncommitted” in the Democratic primary in protest of the Biden administration’s support of the war in Gaza and the Israeli regime, couldn’t get a Palestinian American added to the program. DNC organizers had rejected a substantial list of names of potential speakers. “I saw people invoke Fannie Lou Hamer, and I saw people invoke Shirley Chisholm, and I saw a tribute to Jesse Jackson,” he said. “And then I would be outside, with these Palestinian Americans and sympathizers to Palestinian Americans, and I would see that they had no place.”

In his dispatch for Vanity Fair, Coates drew attention to this failing, referring for the first time in writing to the current military assault in Gaza as a “genocide.”

Personally, I believe that what’s been going on in the Holy Land beginning October 7, 2023 is horrible, and I wish it would stop. But I don’t have any solutions. I encourage those who feel that they do know the right thing to do, including Ta-Nehisi Coates, to debate the subject in public.

I suspect, however, that TNC will soon discover just how sacralized and off-limits to criticism he had been a decade ago when he was almost universally lauded in the Prestige Press for his racist anti-white writings. Back then, nobody was supposed to mention that he’s not at all very bright for a famous public intellectual, because his hate-warped racist nonsense was considered a Good Thing because he was just demonizing whites.

Now, however, TNC’s gotten his courage up to punch more or less sideways, black vs. Jew, rather than straight down, black vs. white, so we shall see whether he gets as shamefully universally ecstatic of a reception now as he did early in the Great Awokening.

Of course, back then, I mentioned TNC’s dimness, repeatedly. Here are my reviews from Taki’s Magazine of Coates’ two celebrated books:

But first:

By the way: I’m doing book tour appearances in Chicago next week to promote my anthology Noticing: dinner on Thursday evening September 26th downtown and a speaking event on Friday night September 27th on Chicago’s north lakefront. See Passage Press’s website for tickets.

The First Rule of White Club

July 29, 2015

I have found that, in the African-American oral tradition, if the words are enunciated eloquently enough, no one examines the meaning for definitive truth.

—Biracial novelist Mat Johnson, Loving Day, 2015

America’s foremost public intellectual, Ta-Nehisi Coates, has published a new best-selling minibook, Between the World and Me, that’s interesting for what it reveals about a forbidden subject: the psychological damage done by pervasive black violence to soft, sensitive, bookish souls such as Coates. The Atlantic writer’s black radical parents forced the frightened child to grow up in Baltimore’s black community, where he lived in constant terror of the other boys. Any white person who wrote as intensely about how blacks scared him would be career-crucified out of his job, so it’s striking to read Coates recounting at length how horrible it is to live around poor blacks if you are a timid, retiring sort.

Coates’ lack of physical courage is a common and perfectly reasonable trait, although writers typically cover it up. For example, Hunter S. Thompson transmuted his recurrent paranoia about impending carnage (which beset him even in venues as family-friendly as the Circus-Circus casino) into hallucinatory comedy in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Coates, however, is humorless. Worse, his fans have encouraged him to believe he is the second coming of James Baldwin, egging him on to indulge in a prophetic-hysteric-postmodern style that is easier to parody (e.g., just repeat endlessly the phrase “black bodies“ and the distractingly stupid formulation “people who believe they are white”) than it is to endure over even the course of Coates’ very short second autobiography. (As with the president, both of Coates’ books are memoirs.)

White writers have seldom had the courage to confess their fear of black violence so fully, at least not since 1963, when Norman Podhoretz responded to the hullabaloo over James Baldwin with an essay about growing up in Brooklyn in the 1930s and 1940s:

And so for a long time I was puzzled to think that…Negroes were supposed to be persecuted when it was the Negroes who were doing the only persecuting I knew about — and doing it, moreover, to me…. A city boy’s world is contained within three or four square blocks, and in my world it was the whites, the Italians and Jews, who feared the Negroes, not the other way around. The Negroes were tougher than we were, more ruthless, and on the whole they were better athletes…. Yet my sister’s opinions, like print, were sacred, and when she told me about exploitation and economic forces I believed her. I believed her, but I was still afraid of Negroes.

In the 52 years since Podhoretz’s “‘ My Negro Problem’ And Ours,” overwhelming evidence has piled up validating the prescience of his boyhood traumas at the hands of black juvenile delinquents. But it’s precisely because the scale of black violence over the past half century is so blatantly obvious that white intellectuals have been largely self-silenced on the topic — even as the most cunning minds among today’s liberal whites plot to reverse the mistake their grandparents made in fearfully ceding much of the best urban turf to black criminality.

The central real estate question of this century has become: How can big cities drop their hot potato of poor urban blacks in the laps of naive suburbs and small towns? That helps explain the unhinged reaction among elites to Donald Trump publicly pointing out that Mexico isn’t sending us its highest-quality citizens to be our illegal aliens. The unspoken plan is to continue to use the more docile Hispanics newcomers to shove the more dangerous African-American citizens out of desirable cities; thus, only a class traitor like Trump would dare allude to the unfortunate side effects suffered by the rest of the country.

Despite all the violence Coates has suffered at the hands of other blacks, his racial loyalty remains admirably adamantine. Thus, his ploy, as psychologically transparent as it is popular with liberal whites, is to blame his lifelong petrified unhappiness on the white suburbanites he envied for being able to live far from black thugs.

Unfortunately for Coates’ persuasiveness, white people, unlike blacks, have never actually done anything terribly bad to him. The worst memory he can dredge up is the time an Upper West Side white woman pushed his 4-year-old son to get the dawdling kid to stop clogging an escalator exit. She even had the racist nerve to say, “Come on!”

Coates reacted as unreasonably as a guest star on Seinfeld would. Ever since this Escalator Incident, he’s been dwelling on how, while it might have looked like yet another example of blacks behaving badly, it was, when you stop to think about slavery and Crow (not to mention redlining), really all the fault of whites.

The central event in Between the World and Me is the fatal shooting in 2000 of an acquaintance from Howard U. by an undercover deputy from Prince George County, the country’s most affluent black-majority county. Coates refers to this tragedy repeatedly as proof of America’s demonic drive to destroy black bodies. (The dead man’s family, I found, was eventually awarded $3.7 million in their wrongful-death suit, much like the $3 million awarded to the parents of a teen gunned down by an undercover Obama Administration agent in a shooting that I investigated in 2010. You have never heard of my local police blotter item, though, because the victim was white.)

Since I’m a horrible person, my immediate response to Coates’ tale was…okay…black-run county, affirmative-action hiring, and poor police decision-making…you know, I bet the shooter cop was black.

And sure enough, the Carlton Jones who shot Prince Jones turned out to be black. Coates eventually gets around to briefly admitting that awkward fact, but only after seven pages of purple prose about people who believe they are whites destroying black bodies.

In fact, I discovered Coates himself had written about this tragedy before. Seven years ago he explained in The Atlantic in a poorly proofread but less pompous prose style:

I am going to try to be fair about this. The cop was in an unmarked car, and wasn’t wearing a uniform. According to his own testimony, he basically cornered Prince’s car pulled out a gun — but no badge — and IDed himself as an officer. Prince. whose vehicle was hemmed in, rammed the cops car. The cop shot him Prince and he died. The officer was presumably in pursuit of a “suspect.” But the suspect looked nothing like Prince, except that they were both black. All I could think when that happened was about what I would have done. The way we come up, if a black dude with dreads (which is how officer Carlton Jones looked) is following you and then he corners you, pulls a gun, but doesn’t have a badge, you don’t assume he’s cop. You assume he’s trying to rob you.

In other words, the two black men racially profiled each other as dangerous criminals and then violently attacked each other.

Why did the two blacks profile each other?

Oh, sorry, I forgot: because white people.

Wait, my mistake: because people who believe they are white.

Occam’s razor suggests that the reason blacks tend to fear violence from one another is because they tend to be violent.

But you are forgetting something: The first rule of White Club is: You do blame White Club. The second rule of White Club is: You do blame White Club.

Coates has thus elaborated a theory of history in which everything bad ever done by blacks is the fault of American whites (whom he describes — metaphorically, I hope — as “cannibals”).

Unfortunately, Coates, a 39-year-old Howard U. dropout, doesn’t actually know much about history because, even though he frequently reads history books, he lacks a retentive mind. He reminds me of another autodidact who is always amazed by whatever he is currently reading: Glenn Beck.

Coates is unable to keep in his head a coherent timeline of the past, which means he is frequently clueless about what could possibly have caused what. For example, when recounting his arrival at Howard U. around 1993, he complains that outside his HBCU “black beauty was never celebrated in movies, in television…” Personally, I watched a lot of television in 1993, and my recollection is that the beauty of Michael Jordan’s black body was rather often celebrated. But who can expect the New James Baldwin to remember 1993?

The intellectual limitations that have helped Coates achieve his level of conventional wisdomhood include his lack of interest in races other than blacks and whites. The country has 55 million Hispanics, 17 million Asians, and 4 million American Indians, yet Coates has barely deigned to notice their existence, much less ask himself why they have their own problems, which are on average quite different from black problems.

History, for Coates, began in 1619 with the first blacks to arrive in America. He has no interest in what blacks brought with them from their tens of thousands of years of evolution in Africa. (He appears wholly ignorant of science.)

And history sort of peters out for Coates and his admirers about 50 years ago, when liberals took charge of race in America. For instance, Coates is convinced that redlining by the FDR Administration explains why the West Side of Chicago is like it is. But he had no interest in learning from, say, Alyssa Katz’s 2009 book Our Lot, which documents how Chicago’s once crime-free Austin neighborhood (from which my wife’s family was driven in 1970 after the third felony committed against the children by blacks) was destroyed by the liberal 1968 Fair Housing Act.

There are tens of millions of Americans who remember being shoved out of formerly functioning urban communities by black criminality. But who speaks for them? Will they ever be allowed to publicly commemorate the injustice that was done to them?

And two years later, I reviewed Coates’ next book in Taki’s Magazine:

Ta-Nehisi Coates: “All Is Fog”

October 25, 2017

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Source: Eduardo Montes-Bradley

Which trait most accounts for the spectacular career of Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Atlantic’s race blogger–turned–intellectual superstar?

Coates, widely assumed to be America’s foremost public thinker, has published yet another best-seller: We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy. In his new $28 book, Coates reprints his old magazine articles that The Atlantic had given away for free, sandwiched between what he enticingly labels “extended blog posts” about what kind of mood he was in when he wrote each article.

A couple of years ago, Coates was awarded a MacArthur Foundation genius grant of $625,000 for his best-selling micro-memoir Between the World and Me, in which he recounted not just one but two anecdotes about people he knew who were the victims of white racist oppression.

In one, a black guy whom Coates had vaguely known in college was gunned down by a policeman.

Eventually, Coates admits the shooter cop was black too, which you might think wrecks the moral of his tale. But that’s not the point; the point is that, no matter what blacks inflict upon one another, white people are to blame.

And that’s not all Coates could remember from his first forty years of life. His memoir also included the celebrated story of how Coates let his little boy dawdle upon an escalator and then a white woman about to crash into the lad said, “Come on,” which is racist.

These two thrilling yarns have rocketed Coates to near the top of the college speaker circuit, where he makes up to $1,000 per minute on the nights when he can’t think of enough to say about White Supremacy to fulfill his contractual minimum speech length of 75 minutes.

What exactly is the secret of Ta-Nehisi’s success? Why has he vaulted over more talented black intellectuals such as John McWhorter and Thomas Chatterton Williams (who have both been unloading on Coates lately)?

It’s definitely not his erudition. McWhorter scoffed recently:

The elevation of that dorm-lounge performance art as serious thought is a kind of soft bigotry, which is as nauseating as it is unintended.

Nor is it that Coates has a charismatic personality. He has zero sense of humor and a sententious prose style. He’s a soft, timid comic-book nerd who emits hilariously white sentences like:

But whereas his forebears carried whiteness like an ancestral talisman, Trump cracked the glowing amulet open, releasing its eldritch energies.

Coates grew up physically scared of other blacks, which is one reason he has so few interesting stories from his 42 years of life: He didn’t go out much.

So what has made this rather pathetic person so immensely popular with whites?

The secret behind Coates’ appeal to white liberals is that he’s not very smart. He’s not likely to bring up awkward facts that don’t fit The Narrative. Why not? Because he can’t remember them.

Coates’ lifelong worries about his lack of mental retentiveness are a recurrent theme in We Were Eight Years in Power:

…the classroom had always been the site of my most indelible failures and losses…. I wondered then if something was wrong with me, if there was some sort of brain damage…. And like almost every other lesson administered to me in a classroom, I don’t remember a single thing said that day.

Coates sums up:

I’d felt like a failure all of my life—stumbling out of middle school, kicked out of high school, dropping out of college.

His failure to graduate from Howard U. ate away at him for most of the next decade:

…my chief identity, to my mind, was not writer but college dropout…

Fortunately, a loyal girlfriend supported him into his 30s as he failed in various ill-paid journalism jobs:

Kenyatta and I had been together for nine years, and during that time I had never been able to consistently contribute a significant income.

Kenyatta believed in him as a writer, despite his deficiencies of style and substance:

And so I derived great meaning from the work of writing. But I could not pay the rent with “great meaning.” I could not buy groceries with “great meaning.” With “great meaning” I overdrew accounts. With “great meaning” I burned through credits cards and summoned the IRS.

Coates has a hard time remembering much besides his feelings. For example, the last three words of his account of a seventh-grade trip to Gettysburg reveal a repeated theme in Coates’ rise to best-selling memoirist:

Given this near-totemic reverence for black history, my trip to Gettysburg…should cut like a lighthouse beam across the sea of memory. But when I look back on those years…all is fog.

This is not to say that Coates’ memory is worse than average, just that as a professional memoirist he’s not exactly Vladimir Nabokov penning Speak, Memory. Moreover, Coates doesn’t remember much of what has been in the news in recent decades, which is a little odd for a journalist.

Mr. Sailer is assuming the role of Tom Wolfe in interpreting these New York status games for our generation.

It's worth pointing out, as Steve did in one of these essays, how much people like Coates work hard to get away from other black people and their output is a sort of perverted deflection. When flush with book advance money he didn't snag a brownstone in Harlem but in hipster Brooklyn. I read an account years ago from someone who happened to be at some gathering of the connected at which TNC was an honored guest and it was remarked upon how it was like 90% white and smattering of everyone else but he seemed at home in that environment. I think at some level he recognizes this in himself and hates it, since so much of his childhood revolved around his fear of *real* blackness.