Ancient Civilizations?

Have archeologists ignored evidence for earlier technological development?

The TV show Ancient Civilizations presents a fun case for the theory that fairly advanced civilizations existed before orthodox scholars imagine. Representative tagline:

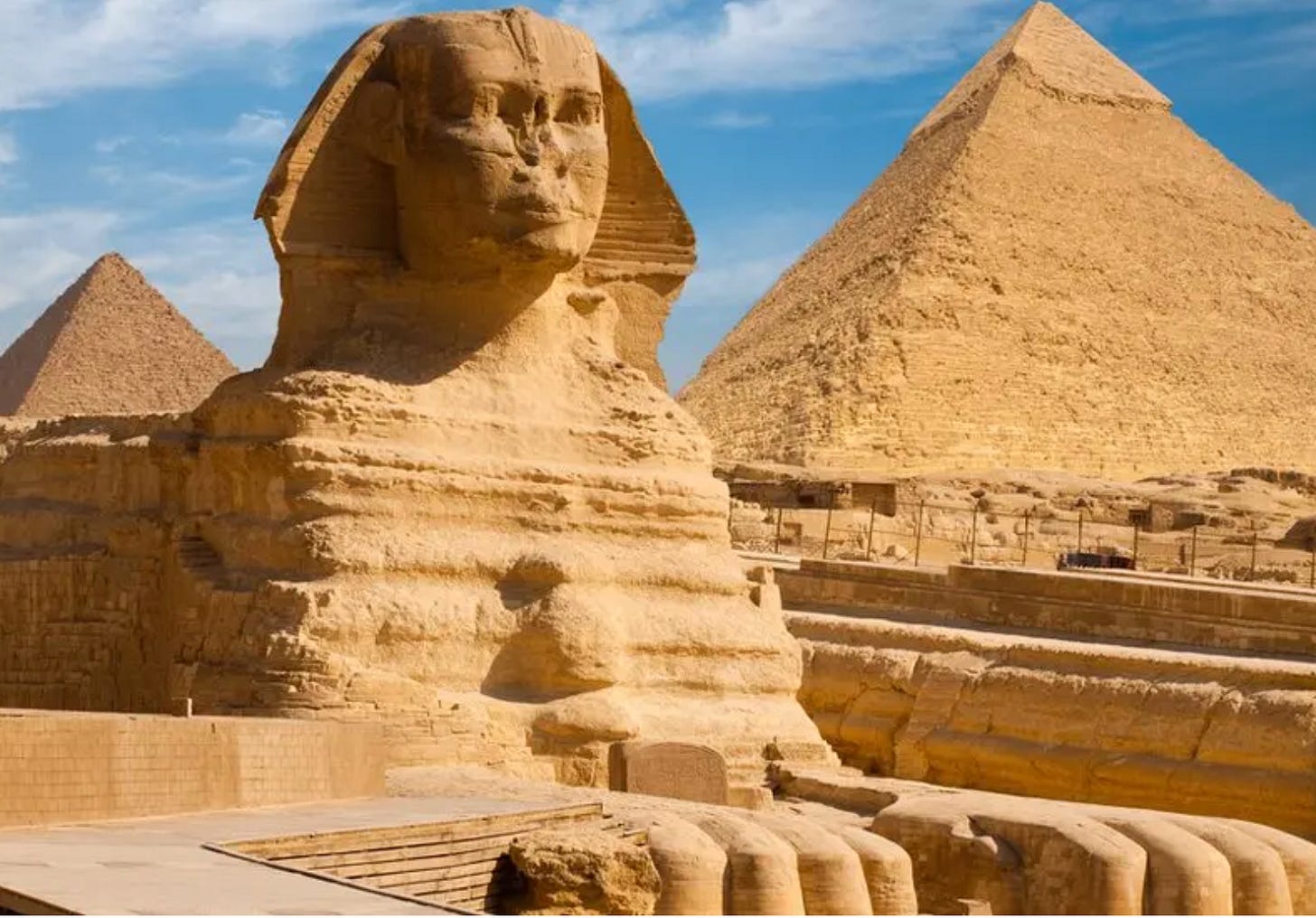

The great sphinx of Giza, the oldest known monument from the ancient Egyptian world, stands as a symbol of the arcane mysteries still waiting to be unearthed.

U. of Iowa paleoanthropologist John Hawks doesn’t think much of the specifics of these theories. But he is sympathetic to the notion and/or conspiracy theory that archaeologists long overlooked evidence of technological advancement in not just ancient humans but even in hominins (e.g., Neanderthals) in general. Hawks writes on his Substack:

I ran across this question on my social feed today. Someone claimed that in as few as 10,000 years, nature would erase all traces of human existence.

You hear this idea every so often, and the people who bring it up usually have an ulterior motive. If our civilization could be erased in a short time, they say, then maybe today’s archaeologists have missed subtle traces of lost cultures far more advanced than our own. If we can imagine future archaeologists oblivious to today’s cities, something equally huge may be waiting for us to discover from past times.

Ten thousand years is far too short a time to erase some of the signs of civilization. Pyramids and kurgans have lasted nearly five thousand years already.

A hundred thousand years hence, colossal wrecks of debris will mark where Phoenix, Las Vegas, Riyadh, Johannesburg, and hundreds of smaller cities stand today—all places where rainfall is sparse and off-floodplain land surfaces are stable.

The tallest building in Las Vegas is either, depending upon how you define “building,” either the 1,149 foot Strat tower or the recent 737 foot Fontainebleau hotel.

Buildings will crumble, but fragments of float glass, ceramic tile, exotic stone and xeriscaping quartzite imported from thousands of miles away will make the legacy of human presence obvious.

Depending upon whether or not they get covered by blown sand and dust.

Still, modern buildings can so colossal that even if they collapse, they’d be unlikely to be covered up, just as the 4500 year old pyramids of Giza aren’t close to being inundated in sand.

More subtle effects of our presence will be less apparent to the eyes but will yield easily to scientific analysis. Cores taken from lake bottoms contain pulses of heavy metals settled from the atmosphere after our burning of coal. The common dandelion, the black rat, the zebra mussel, the cane toad, and thousands of other species live today in places far from their biogeographic origins—impossible to explain without our global transport networks.

Future archaeologists won’t lack for evidence of our existence, even if they have come from interstellar space.

Ancient traditions overlooked

Still, that doesn’t actually answer the question of what past cultures archaeologists may be missing today. Consider what has emerged within the past few years as a result of archaeological detective work:

Wooden structures. A half-million-year-old structure made from shaped and notched logs preserved at Kalambo Falls, Zambia. The preservation of wood is very rare across such long time periods. But archaeologists have added more and more evidence of the diversity and craftsmanship of wooden tools from older and older sites. In light of this kind of evidence, I think it’s fair to say that archaeologists have long underestimated the technological abilities of many hominin species.

“Fat factory”. The site of Neumark-Nord, Germany, a 125,000-year-old lakeshore where Neanderthals hunted and had their behavior captured by sediment deposition, has a massive scatter of bone fragments from more than a hundred large mammals. The pattern of breakage of the bones shows that Neanderthals were boiling these in water to extract the bone grease, one of the big energy and nutrition-rich parts of a skeleton. The scale of the Neumark-Nord evidence is massive, suggesting it was part of a long tradition of culinary extraction—comparable in scale to some of the intensive foraging societies of the last 10,000 years. Archaeologists like John Speth had long speculated that Neanderthals might have boiled water and degreased bones in perishable containers like skins or birch, but these suggestions rooted in ethnographic descriptions of historic foragers were generally politely ignored when it came to Neanderthals.

Landscape engineering. Neumark-Nord also has provided some strong evidence for Neanderthal use of fire to shape landscapes. Burning forested areas and refreshing grasslands is a common strategy for attracting game among recent foraging peoples. The practice has also been demonstrated in Malawi where the pattern of charcoal production from landscape burning increased markedly during MSA times from at least 85,000 years ago. A decade ago, many archaeologists were arguing that Neanderthals could not even reliably control fire; now it is clear that fire was used for intentional landscape ecology across continents.

Tree management. Ancient people were shaping ecology by spreading seeds and possibly cultivating trees long before agriculture appeared. One of the most evocative examples is in Australia, where boab trees (Adansonia gregorii) were subject to intentional human dispersal by foraging peoples.

Water transport. Just over twenty years ago, archaeologists commonly argued that dispersal of hominins across deep water barriers was impossible before around 50,000 years ago—despite 1950s-era reports of older stone tools on Flores, the Philippines, and other islands. The 2005 reporting of the Liang Bua, Flores, finds including Homo floresiensis transformed thinking about hominin dispersal. Subsequent work established Middle Pleistocene hominin presence on Sulawesi and Luzon. Some artifacts hint that Neanderthals may have reached some Mediterranean islands.

Every one of these examples has been exciting to see. Not one is a discovery of a unique event; every one of them demonstrates that one or more populations sustained traditions over a long time.

Together the implications of such discoveries are profound: Cultural traditions that spanned millennia were not merely overlooked; in many cases archaeologists had argued strongly against the evidence, based on the idea that such traditions were beyond the capabilities of our Pleistocene relatives.

Granted, boiling off bone grease isn’t as cool as building the Sphinx, but still …

Gobeleki Tepi, the Sphinx and the pyramids suggest that there was some sort of a civilation that was destroyed prior to the Younger Dryas. It may have been largely maritime in nature leaving all traces of it submerged by the rising ocean. Underwater archeology is notoriously difficult. What we know will always be just a fraction of what we don't.

Comment on X: "guy 10,000 years from now putting lead and plastic in his food for the "Anthropocene Diet", eaten by his ancestors who built the Bass Pro Shops Pyramids and the Great Underwater City of Miami".