Another Pretendian

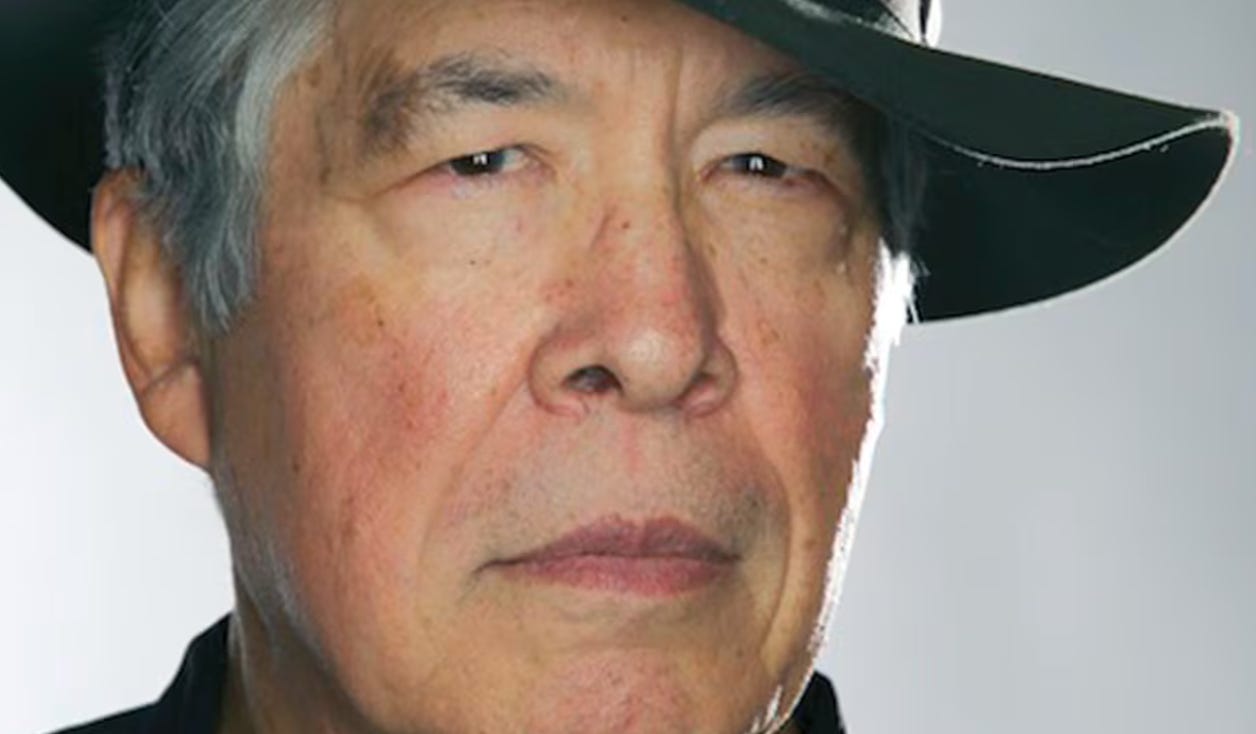

Canada's top First Nations writer, Thomas King, reveals he isn't Cherokee.

It’s rare in the United States to hear of white men pretending to be black despite the affirmative action benefits. But whites, especially academics and writers, frequently claim an American Indian identity. Much the same is true in Canada, where, for example, folk singer Buffy St. Marie was exposed as a Pretendian a few years ago.

Similarly, Canada’s top Native writer and a long-time Native Studies academic, 82-year-old American-born Thomas King, just announced that it had been proven to him by a genealogist that he had no Cherokee ancestry. Personally, I’d never heard of the guy, but he’s apparently a big deal in Canada where there’s a hunger for verbally adept, sober First Nations representatives, similar to how Australian media is always celebrating their First Aboriginal Quantum Theorist or whatever and then showing you a picture of somebody who looks 15/16th Scottish.

The difference between Australia and Canada is that it’s against the law to publicly question just how indigenous somebody is down under, while it’s a popular sport in Canada.

King at least looks part non-white, although probably more East Asian than Amerindian.

He was born in California in 1943. His Oklahoma-born father ran off when he was three. King writes in the Opinion section of the Toronto Globe and Mail:

At 82, I feel as though I’ve been ripped in half, a one-legged man in a two-legged story. Not the Indian I had in mind. Not an Indian at all

Thomas King

The Globe and Mail

Published November 24, 2025

… So, he [my father] wasn’t a part of my life. But he came back into focus, when I was about 11 or 12.

My brother and I didn’t look like the rest of the family. We were much darker. I have a family picture from the period, and the difference between the two of us and our cousins is marked. Secondly, I looked somewhat Asian.

The Second World War had ended in 1945, two years after I was born. The Korean War had wrapped up in 1953. So, imagine my amusement, when some of the kids in the neighbourhood decided that, given the times and my appearance, I must be “a Jap.”

I took the matter to my mother. No, she told me, you’re not Japanese. Your father is part Cherokee. That’s what the kids are seeing.

My mother never talked about my father. Why would she? The son of a bitch had deserted her. Still, I was curious about the man. So, I probed. And by the time I was in my late teens, I had compiled an intriguing if somewhat fractured story.

My father grew up in Oklahoma. When he was in his mid-to-late teens, he discovered that the man who was his father of record, William King, was not his biological father. According to oral family history, his biological father was a man named Elvin Hunt. From what my mother could gather, my father was not pleased with this turn of events. He liked King, disliked Hunt, and he was even less pleased because Hunt was part Cherokee.

So if his illegitimate grandfather Elvin Hunt was, say, half Cherokee, then his father would be one quarter, and he’d be one-eighth Cherokee.

Years later, when I was in my late 60s, my brother and I located our father’s oldest sister. …

And she told us the same story my mother had told me. Yes, Elvin Hunt was really our father’s father. Yes, he was part Cherokee. But the detail that most intrigued her, and that she touched on several times, as she arranged the photographs on the table, was that he “was very, very dark.” Knowing a little of the history of the Freemen among the Cherokee, I asked her if he could have been part Black as well. She just kept moving the pictures around and repeating that he “was very, very dark.” …

While I have had my fair share of run-ins with smiling bigots and sympathetic racists, I have also benefitted from being considered Native American, and if I were a journalist covering this story, I would ask the following questions:

Mr. King, did you benefit from grants earmarked for Native scholars?

Did you benefit from being Native in the job market?

Do you think your Nativeness gave you unwarranted access to publishing, radio, television, and other artistic avenues that you would not have had as a non-Native?

Would the perception and reception of your writing have been different had you not identified as Native?

Do you think the publication of your work prevented the publication of similar work by a Native author?

And then there will be the harder question, the question that will be on many people’s lips as they read this: Did you know that you weren’t Cherokee all along and simply perpetrate and maintain a fraud throughout your professional life for fame and profit?

While the answers to the other questions are problematic, the answer to this last one is a simple, hard, no.

Not that this will keep people from believing what they will. Human nature loves blood in the water. …

Mind you, going forward is going to be difficult, if not impossible. Will I try to step sideways into the sphere of the Tony Hillermans, the Evan S. Connells, the William Eastlakes, non-Natives who wrote about Natives? The Helen Hunt Jacksons and the Dee Browns of the world?

Why no mention of DNA testing?

Paywall here.