Changes in Altitudes, Changes in Aptitudes?

Can you think harder at high or low elevation?

Jimmy Buffet opined:

It's those changes in latitudes, changes in attitudes

Nothing remains quite the same

Is it true that attitude correlates with latitude?

I don’t know, but it’s interesting to think about.

What about changes in altitudes, changes in aptitudes?

Back in the 1990s, an in-law started up an ambitious software firm in Albuquerque, NM. I asked him why he didn’t pick Santa Fe, which seemed more fashionable.

He replied that he found that the difference in altitude between Albuquerque (elevation 5,300 feet) versus Santa Fe (elevation 7,000 feet) made it easier to get hard mental work done in the lower city.

Is that true?

I’ve been wondering about that ever since.

Clearly, high altitude hurts physical endurance. The 1968 Summer Olympics at Mexico City (7,300 feet) saw record times in the sprints due to less wind resistance on sprinters, but slower times in the long races. (It wasn’t due to lack of acclimation: the US Olympic team held their track trials outside of Lake Tahoe at 7,400 feet the previous month, and then stuck around to train at altitude.)

What about cognitive performance?

A 2022 meta-analysis in Brain Science suggests people can think better at high altitude:

Brain Sci. 2022 Dec 19;12(12):1736. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12121736

Cognition and Neuropsychological Changes at Altitude—A Systematic Review of Literature

Kathrin Bliemsrieder, Elisabeth Margarete Weiss, Rainald Fischer, Hermann Bruggee, Barbara Sperner-Unterweger, Katharina Hüfner

Editor: Adriana Salatino

Abstract

High-altitude (HA) exposure affects cognitive functions, but studies have found inconsistent results. The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the effects of HA exposure on cognitive functions in healthy subjects. A structural overview of the applied neuropsychological tests was provided with a classification of superordinate cognitive domains. A literature search was performed using PubMed up to October 2021 according to PRISMA guidelines. Eligibility criteria included a healthy human cohort exposed to altitude in the field (at minimum 2440 m [8000 ft]) or in a hypoxic environment in a laboratory, and an assessment of cognitive domains. The literature search identified 52 studies (29 of these were field studies; altitude range: 2440 m–8848 m [8000–29,029 ft]). Researchers applied 112 different neuropsychological tests. Attentional capacity, concentration, and executive functions were the most frequently studied. In the laboratory, the ratio of altitude-induced impairments (64.7%) was twice as high compared to results showing no change or improved results (35.3%), but altitudes studied were similar in the chamber compared to field studies. In the field, the opposite results were found (66.4 % no change or improvements, 33.6% impairments). Since better acclimatization can be assumed in the field studies, the findings support the hypothesis that sufficient acclimatization has beneficial effects on cognitive functions at HA. However, it also becomes apparent that research in this area would benefit most if a consensus could be reached on a standardized framework of freely available neurocognitive tests.

Perhaps, but self-selection seems like an issue.

Paywall here.

The Manhattan Project got a lot of hard work done at Los Alamos’ 7,300 feet. On the other hand, they were using legendary theoretical physicists as engineers.

The ectomorphic Robert Oppenheimer had loved Los Alamos since boyhood, which is why he chose this rather random location. But some of the other famous physicists were not as happy campers. The young Richard Feynman, hardly a lazy tub of lard, found the altitude hard on “flatlanders” like himself, and Fermi and Teller were not enthusiasts for the location either. (I don’t believe the aging Einstein ever visited Los Alamos.)

Say you wanted to study the Great Books at one of the two St. Johns Colleges. Would you learn more in Annapolis at sea level or at Santa Fe (7300 feet)?

Or say that, for reasons, you really want to move to Peru. If so, should you move to Lima (sea level) or Cusco (11,200 feet)?

On Scott Alexander’s Substack, I recently suggested that some people might find Cusco’s altitude difficult. And that made some other people angry and they spent a couple of days calling me a racist for questioning the idea of moving to Cusco rather than Lima.

(I haven’t been to Cusco in 47 years. Apparently, there’s a big expat community there now. The hallucinogen ayahuasca seems to be a big draw, so I’m not sure how much work the Cusco expats really want to get done. Another part of the appeal of Cusco is that more of the locals speak Quechua rather than Spanish, so the expats stick together more in Cusco than in Lima, where they might be tempted to start hanging out with the Spanish-speaking locals.)

Personally, I’ve been obsessed with the effects of high altitude at least since I became a Boy Scout at age 11. My father was a Swiss-American, whose siblings were really into backpacking.

At that age, my uncle gave me his collection of U.S. topographical maps. Besides much of California, my uncle’s topo map trove included his Greatest Hits of 25 topo maps of some of the wilder geology in the U.S. I’ve enjoyed the pleasure of looking out an airliner window decades later and recognizing, “Hey, look, that’s Capitol Reef on my uncle’s map.” (How come Google Maps doesn’t do topography? I devoted much of my adolescence to getting pretty good at interpreting the difficulty of a proposed hike from topo maps at a glance, something that contemporary online maps seldom allow you to do.)

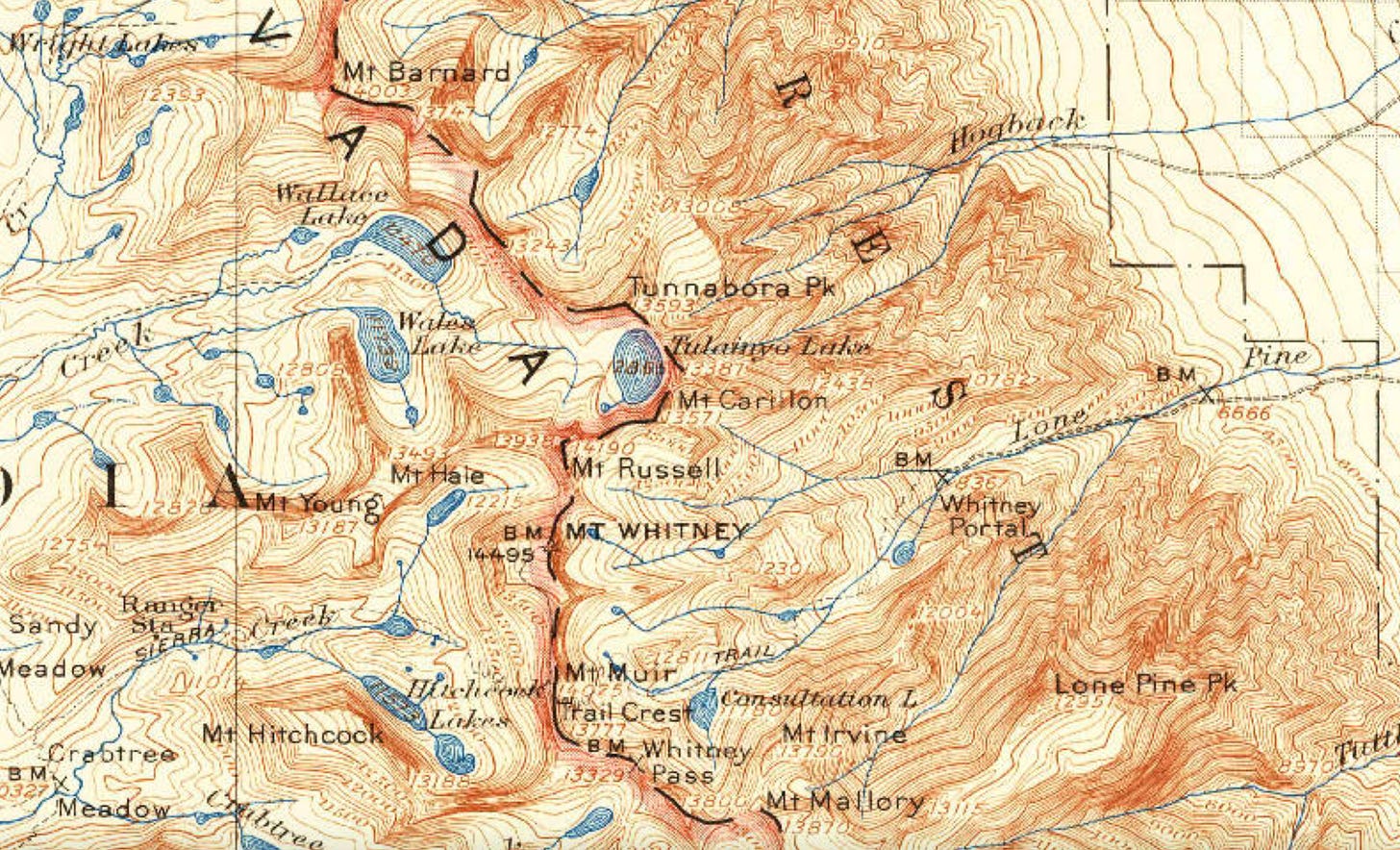

Here’s Mt. Whitney, the highest U.S. mountain outside of Alaska, which I hiked to the top of in 1977. I did pretty well at 14,500 feet, being the only one in my group of five to not pass out immediately upon reaching the summit.

Strikingly, my father, who had a much more rugged constitution than I did below 10,000 feet, had failed to summit Whitney at age 25 in 1942. He hiked from the trailhead at Whitney Portal at 8,367 feet and camped overnight at extraordinary Trail Crest pass, the notch in the Sierra crest, at 13,777.

But the next day he couldn’t get out of his sleeping bag while his friend ascended the last 700 feet to the peak, finally getting up in the afternoon to trudge back down defeated by the thinness of the air.

That my father, who enjoyed hearty health until the last year before his death at age 95, was never able to deal well with extreme altitudes persuaded me in my teen years that altitude aptitude wasn’t just a product of a general factor of fitness or character, but also seemed to vary among individuals.

This notion that you should be sensitive to other people’s altitude aptitude seems to remain controversial.

Most people find it difficult to get really serious work done on a laptop on an airliner. To avoid stressing their aluminum fuselages, airliners are pressurized to the equivalent of 8,000 feet altitude. That’s a major reason Boeing spent a fortune developing its 787 with a carbon fiber fuselage, which is pressurized at 6,000 feet equivalent.

Generally, people acclimate to higher altitudes over a few days or a few weeks. On the other hand, if you have to travel frequently on business, how long does it take you to get back to full speed after returning from the lowlands?

And even if you are fine with high altitude, how do you know you will be in the future? Or somebody close to you in the future?

This is important in retirement planning. There are a lot of nice places to retire to in the American west. Some are at higher altitudes than others.

My uncle built his retirement dream home at 8,900 feet in the Sierra Nevadas, but by the time he was ready to retire, my aunt couldn’t handle the altitude.

That was very sad.

Carrying a child to term at very high altitude can be challenging to those whose ancestors didn’t evolve under such conditions. Pregnant women in Leadville, CO, the highest town in America at 10,100 feet, often spend their third trimester in Denver (5,280 feet) or similar locations. Infants often need oxygen.

On the other hand, you might like the company of the kind of people who self-select for high altitude living, such as the CEO class who have third homes in Aspen, CO (7,900 feet) or Jackson Hole, WY (a less strenuous 6,200 feet). David Brooks wrote in his 2011 book The Social Animal:

Indeed.

On the other hand, I can recall working for a tech startup that was running into major difficulties. The founder decided we’d all get together at his mansion above Aspen for a conference, do some whitewater rafting, maybe go for a 4 WD ride, and then sit down and figure out how to solve all our problems.

Aspen was great!

Except for the part about figuring out how to solve all our problems.

Oh, well …

Looking at that map made me nostalgic for real maps, topographic and road maps. I sometimes want to dump all maps from my phones and buy some real ones. Then I can figure out how to get lost on my own, but at least it will be more aesthetically pleasing.

My company hired a guy who worked remotely from Leadville, CO during Covid. He was a very, very serious ultra marathoner and he told me there were quite a few very, very serious runners who lived in Leadville for the training opportunities.