How Should Colleges Respond to the Asian Inundation?

Can we continue to rely upon admission procedures developed for WASPs during Henry Luce's American Century during our own Asian Century?

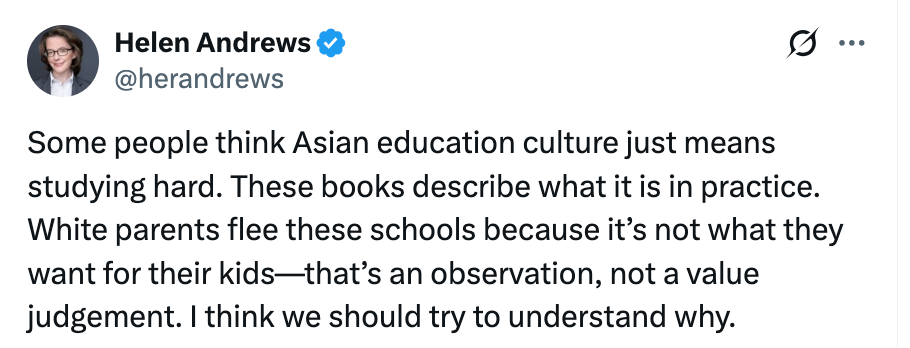

Helen Andrews, who wrote a very nice profile of me three years ago, continues to be a leader of online discussion:

This inspired a large number of Asians to respond that she’s just saying that because whites are racist and inferior.

But the New York Times keep running news articles making Helen’s case for her:

Students Are Finding New Ways to Cheat on the SAT

Sites in China are selling test questions, and online forums offer software that can bypass test protections, according to tutors and testing experts raising alarms.

By Stephanie Saul

Jan. 28, 2026

Three years ago, after nearly a century of testing on paper, the College Board rolled out a new digital SAT.

Students who had long relied on No. 2 pencils to take the exam would instead use their laptops. One advantage, the College Board said, was a reduced chance of cheating, in part because delivering the test online meant the questions would vary for each student.

Now, however, worries are growing that the College Board’s security isn’t fail safe. Fueling the concerns are what appear to be copies of recently administered digital SAT questions that have been posted on the internet — on social media sites as well as websites primarily housed in China.

The SAT leaks dominated the conversation in November at an international education conference in Seville, Spain, according to Angel B. Peréz, the head of the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

“It was the talk of cocktail parties at the international high school conference,” Dr. Peréz said in an interview. “I had a few counselors come up to me to say, ‘we are very concerned.’”

The College Board was alerted to the cheating efforts by an SAT tutor, according to emails obtained by The New York Times. “This is not a matter of one compromised form. It is a multiyear breach of active test material, accessible on a global scale,” the tutor wrote to the College Board in November, according to the emails. …

The SAT is administered seven to eight times a year, and the College Board says its network includes 1,700 testing sites in 187 countries. Students take the test at an SAT-approved site, but they are permitted to use their own laptops. While some colleges, including the Ivy League, made standardized admissions tests optional during the pandemic, many top schools have since reinstated a requirement that applicants submit a standardized test score.

One of the sites — bluebook.plus, an apparent knockoff of the official College Board platform, Bluebook, used to administer the actual test — posts what it says are practice tests that students can pay to access. But some of the questions appear to be real, possibly providing questions that ultimately may appear on a student’s actual exam.

In November, bluebook.plus, which appears from domain name searches to be based in China, had 875,000 visitors, according to an analysis by the web traffic site Similarweb.

The bluebook.plus site did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

Concerns about the security of the digital SAT follow breaches involving other digital tests, including the Law School Admissions Test and Graduate Record Examination.

The College Board said in written statements that SAT cheating is rare, affecting only a fraction of 1 percent of its test scores, and noted that overall test scores have remained steady after the transition to digital tests. “However, some students will always be tempted to cheat on high-stakes assessment, and bad actors are persistent. We stay hypervigilant,” it wrote.

The College Board also acknowledged that, “in certain international markets, bad actors have long made concerted efforts to access and share test content (as well as fabricate content) in order to take advantage of anxious students and parents.”

And today:

In South Korea, Questions About Cram Schools, Success and Happiness

Academic pressure has become so intense that even preschoolers are taking private extracurricular classes, raising worries about children’s rights.

By Max Kim Photographs by Jean Chung

Reporting from Seoul

Feb. 4, 2026

For years, Lee Kyong Min’s life revolved around shuttling her two daughters from school to cram schools to home.

It was a routine followed by nearly every other parent she knew, all sharing the same goal: making sure their children got into South Korea’s best universities. The decisive element was their choice of hagwons, or private cram schools where students take extracurricular classes in math, Korean and English to prepare for the country’s infamously competitive college admissions exam.

Ms. Lee, a former advertising professional, and her husband, who works in finance, had enrolled their children in the best they could find. Seven days a week, she waited for them late into the night at cafes packed with other parents doing the same. Sometimes, she saw little children with schedules so packed that they juggled homework and dinner in those cafes before hurrying off to their next class.

Extracurricular education, which expanded alongside the demand for university degrees as the country shifted to a white-collar economy in the 1990s, is now omnipresent in South Korea. It is also at the center of long-running debates about the consequences of unchecked academic competition. Many parents wonder what alternatives, if any, exist.

When Ms. Lee’s daughters questioned why they had to spend so much time studying outside school, she told them it was necessary because academic achievement equaled opportunity, which meant a happy life.

But her belief in this idea began to fracture when her eldest, then around 8, asked: “Mom, were you a bad student?”

“I realized she saw me as unhappy,” said Ms. Lee, 46. “I felt like I’d been hit in the head.”

Now she wondered: What vision of life and happiness was she presenting to her daughters? It is a question more parents in South Korea are confronting.

South Korea is an amazingly successful country, except for the part about South Koreans dying out.

Eighty percent of South Korean school-aged students now receive some form of private extracurricular education, according to government data. While the schooling-age population has been shrinking for decades, this market grew to a record $20.3 billion in 2024.

Children are entering cram schools at younger ages. In some districts in Seoul, the capital, children as young as 4 take entrance exams for English-language preschools. Others enter medical school prep tracks in elementary school.

Even in a country long inured to intense academic competition, these developments have provoked alarm. South Korea’s human rights commission has said that subjecting preschoolers to such high-stakes testing is a violation of their rights. Lawmakers, blaming hagwons for an adolescent mental health crisis, have vowed to intervene.

The first exam for hiring Mandarins in China was supposedly implemented in the year AD 605, so probably the first test prep centers opened in AD 606.

Note that Asian-Americans are less culturally extreme about test prep and the like than Asians. But still …

As I’ve been pointing out for many years, Harvard notoriously maintains a thumb on its admissions scale against Asians (both Asian-American and foreign) to keep Harvard from …

Paywall here