How to keep the human race from dying out

The abortion rate in the United States tended to decline after the the first couple of decadent decades of legalized abortion following the Roe decision on January 22, 1973. According to the pro-abortion Guttmacher Institute, the number of abortions fell by almost 50% from 1990 to the mid-2010s. Here’s a 2024 graph from Pew about different measures of the number of abortions.

In popular culture, choosing abortion was not popular in songs like Madonna’s “Papa Don’t Preach,” or in films like the late Adrienne Shelly’s Waitress (which is now a Broadway musical) and Diablo Cody’s Juno.

I don’t write about abortion much, but it’s basically grotesque to think about. So it’s a lot more heartwarming to wrap up the plot with a baby’s first cry. Hollywood sound editors long said the two most emotionally impactful stock sound clips they owned were a baby’s first cry and Wagner’s Wedding March.

(What happens after that is of course another question, which is why Dobbs has proven a political loser for the GOP.)

But then the number of abortions started to creep upwards during the moral decline years of the Great Awokening.

I don’t know what has happened statistically since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs’ decision a couple of years ago, but definitely the prestige press has been trying hard lately to make abortion more fashionable. That’s a challenge when you stop to think about what goes into aborting an unborn child, but they’re working on it.

On the New York Times op-ed page, however, two leftist lady philosophy professors write a good piece about how progressive women are increasingly defaulting to letting sterility happen to them in the name of choice:

The Success Narratives of Liberal Life Leave Little Room for Having Children

June 10, 2024

By Anastasia Berg and Rachel Wiseman

Dr. Berg and Ms. Wiseman are the authors of the forthcoming book “What Are Children For?: On Ambivalence and Choice.”

… For progressives, waiting to have children has also become a kind of ethical imperative. Gender equality and female empowerment demand that women’s self-advancement not be sacrificed on the altar of motherhood. Securing female autonomy means that under no circumstances should a woman be rushed into a reproductive decision — whether by an eager partner or tone-deaf chatter about ticking biological clocks. Unreserved enthusiasm for having children can come across as essentially reactionary.

Over the past four years, we’ve conducted interviews and surveys with hundreds of young Americans about their attitudes toward having children. These conversations revealed that the success narratives of modern liberal life leave little room for having a family. Women who want kids often come to that realization belatedly, at some point in their early 30s — the so-called panic years. …

In this way, the logic of postponement that has been promoted by liberals and progressives — and bolstered by overblown optimism about reproductive technologies — robs young people of their agency. How many children they have, and even whether they have them at all, is increasingly a decision made for them by circumstance and cultural convention. …

… our fellow progressives need to stop thinking of having children as a conservative hobbyhorse and reclaim it for what it is: a fundamental human concern.

The family — recognized as the seat of customs and traditional values — has long been central to the appeal of conservatism. Yet it wasn’t that long ago that Republicans and Democrats fought over who could rightfully claim to be the party of “family values.” …

But in time, liberals and progressives came to shy away from publicly embracing the American family as a symbol and an ideal. After Mr. Clinton was impeached in the wake of his own family-values hypocrisy and George W. Bush was elected with the help of energized evangelical voters, family-friendly rhetoric became anathema to liberals — perceived as phony, intrusive and toxic. (The notable exception was gay marriage, whose legalization was won with the help of arguments that promoted the virtues of families.) Today, the left proudly defends the sacrosanct right to abortion and reproductive justice while almost entirely sidestepping the question of whether having children is a worthy project to begin with.

That was my psephological discovery immediately after the 2004 Presidential election: red states tend to be ones where white women are more likely to be married, and the more legitimate children they have, the better Republicans do in that state as the Family Values Party.

The stark polarization of today’s public discourse has only heightened the left’s wariness of children, both privately and politically. Progressive policy defeats are often met with anti-natalist grandstanding. …

The Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, which overturned the constitutional right to abortion in 2022, has also made liberals and progressives more uneasy with the idea of starting a family. A year after Dobbs, the reproductive-rights journalist Andrea González-Ramírez wrote that she had been contemplating having children in her early 30s, before the Supreme Court’s decision put an end to all that: “I have never been sure that I desire to be a mom, let alone that I desire it enough to assume the risks. These days, however, that door is shut. I choose myself.”

That choice is not uncommon. In a recent study, 34 percent of women ages 18 to 39 reported that they or someone they know had “decided not to get pregnant due to concerns about managing pregnancy-related medical emergencies.” That might sound like a worry about abortion access, but the study suggested that Dobbs intensified ambivalence about having children more generally. Indeed, of the women who said they were forgoing having children because of the Dobbs ruling, about half lived in states where abortion rights were still protected.

One can’t help noting the irony: In permitting the conservative movement to alienate them from the question of whether they want to have and raise children, these liberals and progressives are allowing the right to shape their reproductive agendas in yet another way.

But the partisan framing of the issue is flawed at a more fundamental level. The question of children ultimately transcends politics. In deciding whether to have children, we confront a philosophical challenge: Is life, however imperfect and however challenging — however fraught with political disagreement and disaster — worth living?

To be sure, having children is not the only way to address this question. But having children remains the most basic and accessible way for most of us to affirm the value of our lives and that of others.

… Children are too important to allow them to fall victim to the culture wars.

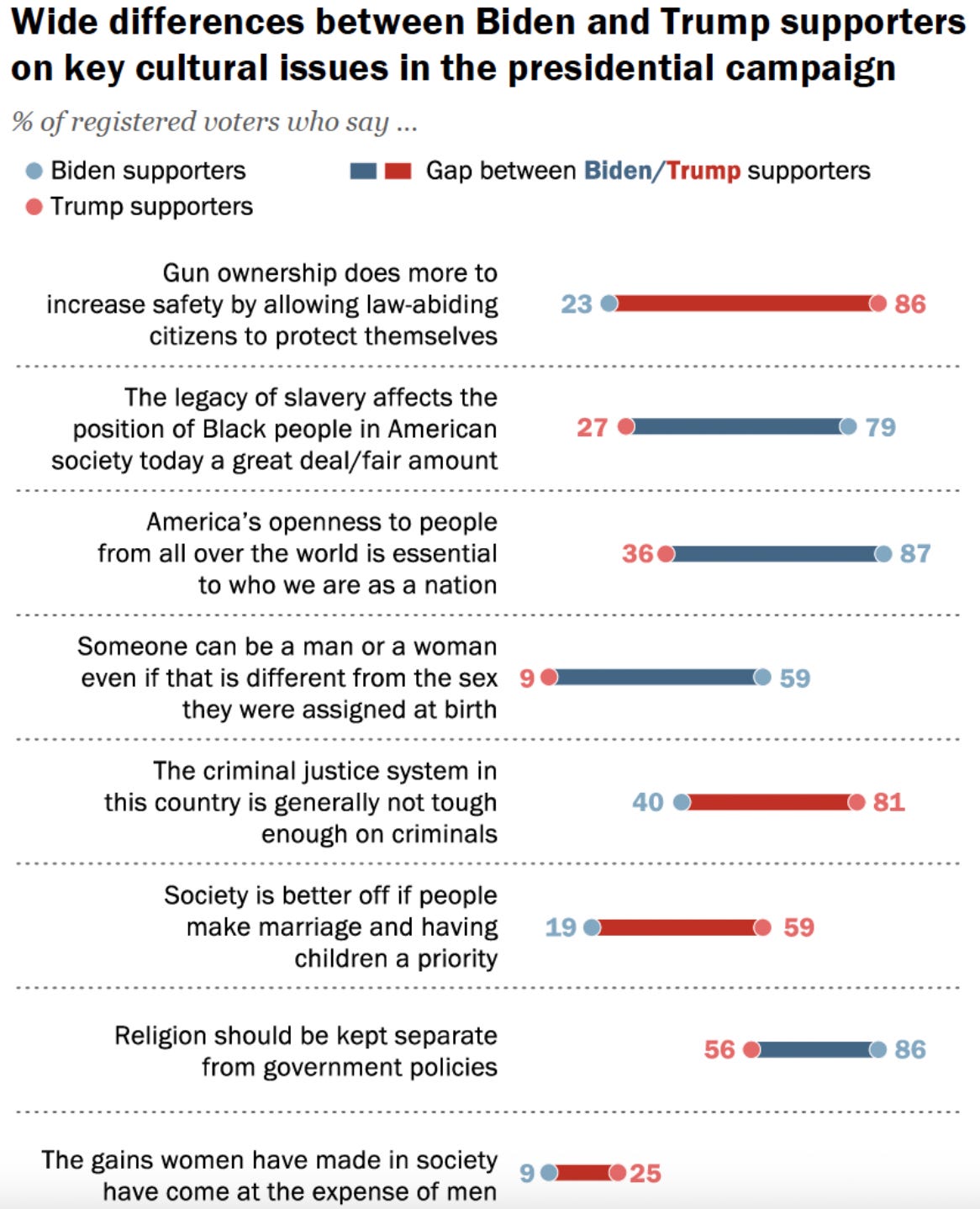

A recent Pew poll found that only 19% of Biden supporters believe “Society is better off if people make marriage and having children a priority.”

Wow, that’s nuts.

What can be done about this trend toward the human race dying out, or at least its 3-digit IQ fraction?

Well, one thing we can do is that older professionals, such as tenured college professors, can cut back on exploiting their underlings so hard that their fertility window is shut by the time they have tenure.

University of Chicago economist John Cochrane in his Grumpy Economist stack was struck by a tweet calling for egg-freezing as a fringe benefit:

It’s worse than Chen thinks. The current standard career track then goes on to 1-2 years as a postdoc, 6-10 years assistant/associate professor, often with “delay the clock” visits to other institutions or “restart the clock” lateral moves. And the current ethic strongly pressures women to delay child-bearing until tenure. It’s also hard to have children when your job lasts 1-2 years so you know you will have to move. That all adds up to a lot closer to 40 than early 30s. And freezing eggs is not magic. Fertility treatment is not guaranteed. Many women who counted on technology discover in their late 30s that biology will not cooperate.

This is a great paradox. In my time as an economist, starting in the mid 1980s, the profession has made great strides to include women. From a faintly hostile and frankly sexist view, most institutions are now bending over backwards to admit, hire, promote, and mentor women. (If you think it’s still bad now, you may be right, but you’re too young to know how much worse it was back then!)

Yet this lengthening of the apprenticeship period, and its effect on women, has gotten a lot worse. In the 1980s, an economists’ career was straightforward: 4 years undergrad, 4 years maximum grad school, 6 years assistant professor, and a pretty good chance of tenure at the first job.

This slowdown, together with the widespread norm that women will wait until tenure before starting families, is particularly difficult for women who wish to have children. As the tweet expresses. Not all women want to have children, of course. And some women may be happy delaying childbirth. But if you want more women, it helps to have more women of all types. If you can include women who want children in something like the natural biological window for doing so, you’ll get more women. If economics departments really did say, on entry to Ph.D. programs, “to all the women, it will be impossible for you to have children before you get tenure, so we have a lovely program that will freeze eggs for you,” I suspect there would be a stampede out, not in. …

the answer is pretty simple: We need to make it possible, acceptable, and normal to begin having children in graduate school. …

Speeding up the career track would help. Given limited demand, that means being more ruthless at each step, weeding out who is really good and talented by means other than an accumulation of degrees, letters, and numbers of publications. But economics has gone exactly in the other direction. Graduate admissions either don’t ask for GREs, or place less emphasis on them. They value pre-doc, masters, letters, and other time intensive preparatory and certification activities instead. The tweet I started with is instructive. Now even pre-doc programs are adding certifications! (I gather that admissions committees are starting to value predocs less. They have seen a few too many letters about the best student ever.) Once in grad school, grades and tests have disappeared. Classes used to require long hard problem sets, hard final exams, and there were first-year comprehensive exams and second year qualifying exams. People actually flunked out of grad school. All that has gone by the wayside.

Another thing that would help would be if full professors didn’t stay in their jobs into their eighties.

Update: On Twitter, @CandideIII points out that the Pew question was worded differently:

Stances on abortion are just vibes about whether you like children or not.

People have always worked, moved, had kids - I don't know what's changed. Yes, it's hard.