Is Baseball 90% pitching?

Can baseball survive the decline of the starting pitcher?

With baseball season gearing up again, the New York Times Magazine runs a long article about the decline of the starting pitcher. If starters aren’t allowed to throw more than 100 pitches per game, how can they achieve traditional superstar pitcher statistics such as 20 wins per season? How can this be good for baseball?

How Analytics Marginalized Baseball’s Superstar Pitchers

Why has pro baseball made it so hard for today’s pitchers to achieve greatness?

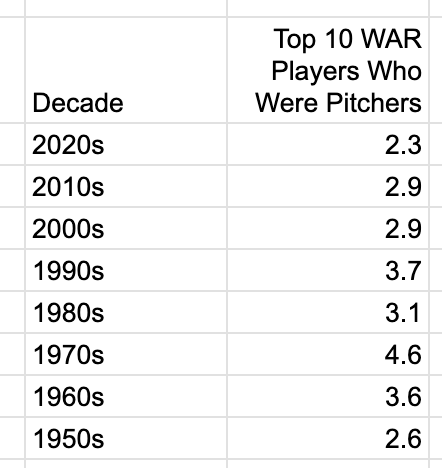

For example, 2024 was the first year since 1961 when none of the top ten players in major league baseball were pitchers, according to the synthetic Wins Above Replacement statistic of all-around value:

Since 1950, pitchers peaked in star value in the 1970s due to the huge number of innings the best pitchers threw at the end of the four-man rotation era.

(By the way, for 2021-2023, I listed two-way superstar Shohei Ohtani as 0.5 pitcher per year.)

So far, the 2020s have had lousy starting pitchers, but not much worse than the 1950s. People who grew up during the 1970s, the great era of starting pitchers, are probably most likely to be dissatisfied with current baseball.

By Bruce Schoenfeld

Mr. Schoenfeld is a frequent contributor to the magazine and the author of ‘‘Game of Edges: The Analytics Revolution and the Future of Professional Sports.’’

March 26, 2025

… Starting pitchers were traditionally taught to conserve strength so they could last deep into games. Throwing 300 innings in a season was once commonplace; in 1969 alone, nine pitchers did it.

Here’s a graph of league leaders in innings pitched from 1950-2024:

Paywall here:

If you go back to first two decades of the the 20th Century, pitchers threw as many as 400 innings in a season because nobody hit homers, so pitchers could throw batting practice fastballs until a baserunner reached scoring position (second base).

After Babe Ruth invented home run slugging in 1919, pitchers had to work harder. But there wasn’t as much emphasis on a regular rotation in the mid-century, so pitchers often didn’t start quite as regularly.

Then in 1961-62, league-leading innings pitched started to rise. Reasons? The season expanded from 154 to 162 games, newer stadiums had more distant outfield fences, the strike zone expanded, the fashionable Los Angeles Dodgers emphasized 300 innings per year from Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax (burning both out by their early 30s in the process, but never mind), and Casey Stengel got fired as manager of the dominant New York Yankees after losing the 1960 World Series while only starting his ace Whitey Ford twice. Stengel saw himself as having artistic insight into when to start and when to sit his pitchers. (Judging by how successful he was, maybe he did.) Stengel was replaced by Ralph Houk, who stuck to a strict schedule for his starters to maximize their innings.

League leading innings pitched peaked in the American League in the early 1970s with Mickey Lolich pitching 376 innings in 1971 and knuckleballer Wilbur Wood matching that in 1972.

But once again, the Dodgers innovated, introducing a five man rotation in 1972-1973, going back to a 4-man rotation in 1974-1975, then permanently returning to the 5-man in 1976. (Although who knows how big their rotation will be this year if boutique starters Shohei Ohtani and Clayton Kershaw ever return. A seven-man rotation?)

Sooner or later, nobody was still using the 4-man rotation. Hence, the last 300 innings season was Steve Carlton in 1980.

The league leading marks for innings pitched then dropped steadily in the 1980s into the mid-2010s. One reason was the increase in the number of batters with home run power meant that pitchers had to work harder to more hitters to keep them from homering.

Then in the late 2010s, this trend toward fewer innings pitched accelerated, when the current jump in velocity and decline in innings pitch grew.

But at some definable point in each game, the data came to reveal, a relief pitcher becomes a more effective option than the starter, even if that starter is Sandy Koufax or Tom Seaver — or Paul Skenes.

That moment usually comes in the sixth or seventh inning, once hitters have had several opportunities to size up the pitches that the starter is throwing. Waiting in the bullpen these days are a cadre of specialists with fresh, powerful arms. …

This has become a problem for Major League Baseball, which needs all the stars it can find. In 1968, Bob Gibson started 34 games for the St. Louis Cardinals and finished 28 of them. In the process, he became a national celebrity. Last season, no pitcher managed more than two complete games.

On the other hand, Carl Yastrzemski leading the American League with a .301 batting average was kind of depressing, so rules were changed for 1969 to encourage hitting. Attendance grew quite a bit in the 1970s and 1980s and then soared in the 1990s due to new ballparks and steroids boosting offense. Fans like slugging more than pitching.

Are great pitchers good for interest in baseball? Great pitchers are pretty to watch on TV, but less so in the ballpark unless you are sitting in a seat that cost three figures.

What fans like in pitching, besides winning pitchers, are heroic pitchers, Sandy Koufax pitching the seventh game of the 1965 World Series on two-days rest, Fernando Valenzuela overcoming the improbability of his own tubbiness, Jack Morris pitching the 10th inning of the seventh game of the 1991 World Series,

Madison Bumgarner coming out of the bullpen in the 2014 World Series, etc…

On the other hand, as the author suggests, the worst combination for fan interest are highly competent but anonymous one-inning relievers.

Six times, pitchers were pulled from games after the seventh inning when they had no-hitters underway. .

M.L.B. can hardly afford to marginalize some of its biggest names by putting them on the field, as [Paul] Skenes was last season, only about 5 percent of the time, and almost never when a game’s outcome was in doubt.

For the importance of marquee starters to be revived, baseball’s executives must somehow persuade managers to act in a way that, the data tell them, is contrary to their teams’ best interests. …

The average length of a pitching start these days is around five innings. It’s hard to base a decision to attend a game on a player who is going to participate in only half of it.

This doesn’t happen in other sports. If you’re at an N.F.L. game and the score is close as it nears the end, you’ll see the star quarterback leading his team down the field. …

On the other hand, American football became much more popular after it stopped requiring players to play both offense and defense. Having separate offensive and defensive platoons was adopted on an unlimited basis by the NFL for 1950 and the NCAA in 1964. Nobody cares that Tom Brady never played a defensive down in the NFL.

Soccer fans no doubt consider that deplorable, but, then again, few care that Lionel Messi makes little defensive effort, saving himself to put goals on the scoreboard.

To be sure, neither football nor basketball has a position so demanding that it requires players to skip games as part of a scheduled routine. “There’s already some inherent acceptance in our game that a starting pitcher is physically incapable of handling beyond a certain workload,” says Mike Fitzgerald, who oversees data analysis for the Arizona Diamondbacks. “But it’s debatable exactly what that workload is.”

What’s not debatable is that the workload used to be far higher. “They’re trying to get you out of the game as quick as they can,” Lance Lynn, who pitched for St. Louis last season, says of the data analysts. “It doesn’t matter what kind of effort you put in. They already have it planned.” The diminished status of the modern starter has put the traditional markers of excellence out of reach. Twenty-four pitchers in baseball history have won 300 games, for example, but nobody else will; the outcomes of too many games are decided from the sixth inning onward, when the starters are already out.

Among active pitchers, Justin Verlander is way out in front with 262 wins, followed by Max Scherzer with 216, and Clayton Kershaw with 212. After that, a big drop down to Gerrit Cole with 153 (and he’s out for the season with an injury). Will anybody ever get to 200 wins again?

In fact, 150 wins is starting to look like 300 wins back in the Don Sutton era. The most wins by anybody under age 30 is 29-year-old Dylan Cease with 57.

“I can’t stand the direction of the game, with all the analytics legislating that you can’t go three times through the lineup,” says Max Scherzer, who pitches for the Toronto Blue Jays, and, at 40, is nearing the end of a glorious career. In 2018, Scherzer struck out 300 batters, one of only 19 pitchers since 1901 to achieve that feat in a season. There is not likely to be another.

Cole struck out 326 in 2019 and Spencer Strider struck out 288 in 2023, so current trends suggest that 300 is still within reach due to the very high rate of strikeouts. Of course, strikeouts require more pitches than groundball outs so they are more debilitating to throwing arms. Greg Maddux won 355 games around the turn of the century by inducing a huge number of outs by his defense. He completed 31 games with under 100 pitches, including a famous 78 pitch gem in 1997.

On the other hand, do we really want pitchers to strike out 1.5 batters per inning? Isn’t it more fun when the ball is put into play?

The loss to baseball transcends the statistical. Starting pitchers are now rarely involved in situations of high drama. “I’m saddened by it,” says Jack Morris, a Hall of Famer whose epic 10-inning shutout won the World Series for the Minnesota Twins in 1991. “Really saddened, in my soul. Will we ever see greatness again? I don’t think we will, because pitchers are not allowed to be great.” …

[Scherzer] offered his solution, a combination of sticks and carrots: If a starter doesn’t throw 100 pitches, go six innings or allow four runs, his team loses the designated hitter for the rest of the game.

On the other other hand, forcing relief specialists to bat sounds boring. Presumably, teams would carry fewer relievers and more pinch-hitters in that case, which would be an improvement.

For recalcitrant teams, Scherzer would also remove the runner who automatically starts each inning after the ninth in scoring position on second base, creating a significant handicap. Once the starter qualifies, his team gets a free substitution, such as the ability to pinch-run for a catcher who still gets to stay in the lineup.

Another idea is that if the starter doesn’t go five innings (assuming he’s not being wrecked by the hitters), he goes on the ten-day disabled list (i.e., he misses his next start).

Still, how important have star pitchers been? A generation ago, Bill James wrote about the old cliche that “Baseball is 90% pitching.” He concluded baseball was about 30% pitching based on evidence such as that teams carried 9 or 10 pitchers on their 25 man roster. He figured baseball was maybe 30% pitching.

Today, teams carry 12 or 13 pitchers on their 26 man roster, and rotate pitchers out of the minor leagues to to start an occasional game more often than they bring up position players. So pitching is getting closer to 50% of baseball.

I looked up the top 500 players in MLB history back into the 19th century on Baseball Reference and 35% were position players. So baseball stardom appears to be about 35% pitching.

This is also part of larger trend across all sports to reduce the risk of injury and fatigue. Nobody in the NBA averages even close to 40 minutes a game anymore, and fans have been complaining about "load management" for years. We may never see another NHL goalie play 70 games in a season. The NFL is on its way to full-time flag football. Sports franchises are now worth billions of dollars, and even middling baseball and basketball players have eight-figure salaries, so there's a bigger investment to protect.

I’m still upset about this newfangled “designated hitter” innovation. Drysdale could hit; Newcombe could hit. Ohtani certainly can hit.

Let’s make pitchers play baseball, not throwball.

If every reliever who entered the game was also obliged to enter the batting order, it might slightly or significantly reduce the number of pitchers used.