No Vibe Shift Visible in the Pulitzer Prizes

Evan Vucci, who took the news photo of the decade, is denied his Pulitzer.

The Pulitzer Prizes were announced today, and they still look much like prize lists from the Racial Reckoning. As I’ve been documenting, in the great marble halls of American prestige culture, there’s not much evidence that the fever dreams of June 2020 have yet passed.

Plus, the anti-Trump resistance seems to be re-organizing. For example, obviously the most historic on-the-spot news photo of last year was AP photographer Evan Vucci’s:

But that photo helped get Trump re-elected, so no Pulitzer for Vucci.

The Pulitzer Prize instead went to NYT photographer Doug Mills for taking the second greatest picture on July 13, 2024, showing a bullet whizzing by Trump’s head:

My guess is that Vucci was denied the Pulitzer because his best shot makes Trump look more heroic-looking.

This is not to say anything against Mills. Both veteran photographers risked their lives to get their memorable pictures. Splitting the prize between them would have been fair and fitting. But reasonable compromises like that are not yet back in fashion among the culturally powerful.

The biography category also caught my eye. Five of the last seven winners have been of blacks (six of seven if you give credence to Gore Vidal’s gossip that everybody who was anybody in Washington knew that J. Edgar Hoover was a black man passing as white).

This year, the winner, Every Living Thing: The Great and Deadly Race to Know All Life by Jason Roberts, dared portray two Dead White European Males, the 18th naturalists Linnaeus and Buffon.

But the book was recognized because of its efforts to have Linnaeus cancelled for not believing in today’s Race Does Not Exist conventional wisdom. From the New York Times’ review:

Paywall here. Post-paywall I recount Buffon’s theory of American Degeneracy and Thomas Jefferson’s Stuffed Moose Rebuttal.

The Two Men Who Wanted to Categorize ‘Every Living Thing’ on Earth

Jason Roberts tells the story of the scholars who tried to taxonomize the world.

By Deborah Blum

Deborah Blum, the director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at M.I.T., is the author of “The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the Twentieth Century.”

April 8, 2024

… If this sketch of Linnaeus causes you to view the man as ruthless, a little unhinged and a lot meanspirited, well, that’s the point here. Jason Roberts, the author of “Every Living Thing,” is not a fan of the founding father of taxonomy, whom he rather hilariously describes as “a Swedish doctor with a diploma-mill medical degree and a flair for self-promotion.” But the snark is not merely entertainment — the portrait is central to the main thesis of Roberts’s engaging and thought-provoking book, one focused on the theatrical politics and often deeply troubling science that shape our definitions of life on Earth.

Roberts’s exploration centers on the competing work of Linnaeus and another scientific pioneer, the French mathematician and naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon. Of the two, Linnaeus is far better known today.

That’s because he invented the taxonomical system that’s still used in, for example, the Endangered Species Act.

Of course, Roberts notes, the Frenchman did not pursue fame as ardently as did his Swedish rival. Linnaeus cultivated admiration to a near-religious degree; he liked to describe even obscure students like Rolander as “apostles.”

Linnaeus inspired a large number of young scientists to risk their lives exploring the earth to discover its species. Buffon was far less enterprising at creating new knowledge, which proved embarrassing to Buffon in his disputes with Franklin and Jefferson over his anti-New World prejudices.

… But perhaps their most important difference — one that forms the central question of Roberts’s book — can be found in their sharply opposing ideas on how to best impose order on the planet’s tangle of species.

Linnaeus is justly given credit for applying logic and order to science, standardizing the names, definitions and classifications of research. But his directives were based on an often uncharitable and deeply biased worldview. He saw species, including humans, as needing to be ranked according to European values. Thus, Linnaeus is also credited with establishing racial categories for people.

He placed white Europeans firmly at the top. Homo sapiens Europaeus, as he called it, was blond, blue-eyed, “gentle, acute, inventive.” By contrast, Homo sapiens Afer was dark and, in Linnaeus’s definition, “slow, sly and careless”; Homo sapiens Americanus was red-skinned and short-tempered.

Buffon, far more generous by nature, rejected this racial hierarchy. “The dissimilarities are merely external,”

That’s why 21st Century DNA tests aren’t able to distinguish people of different races.

Oh, wait …

he wrote in 1758, “the alterations of nature but superficial.” Living things were adaptable, he insisted, shaped by the environment. Charles Darwin, who pioneered the theory of evolution, would later call Buffon’s ideas, posed more than a century before the 1859 publication of “On the Origin of Species,” “laughably like my own.”

After all, everybody knows Darwin was as anti-racist as Ibram X. Kendi. But, now, Darwin’s cousin Galton was Darwin’s Evil Twin. Or something.

Roberts stands openly on the side of Buffon, rather than his “profoundly prejudiced” rival. He’s frustrated that human society and its scientific enterprise ignored the better ideas — and the better man. And he’s equally frustrated that after all this time we’ve yet to fully acknowledge Buffon’s contributions to our understanding. As time has proved him right, certainly on issues of race and evolution, Roberts asks, why are Linnaeus and his worldviews still so much better known — and better accepted by far too many?

The obvious reason Buffon isn’t more venerated in America is because of Buffon’s theory of American Degeneracy. There is no mention in the review of Thomas Jefferson’s ire at Buffon’s popular theory that New World species were degenerate, weak, and stunted in size compared to the more flourishing Old World series. From American Scientist:

In his ninth volume, published in 1761, Buffon compared mammalian species and noted examples in which the same species lived on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. He claimed the New-World versions were always smaller and weaker. European livestock exported to America were always stunted. Species indigenous to the New World were always smaller than comparable species in the Old World (the largest American mammal was the tapir, nowhere near the size of an elephant). Of American Indians, he wrote, "the organs of generation (of the savage) are small and feeble. He has no hair, no beard, no ardour for the female. Though nimbler than the European, his strength is not so great. His sensations are less acute; and yet he is more timid and cowardly." And so on.

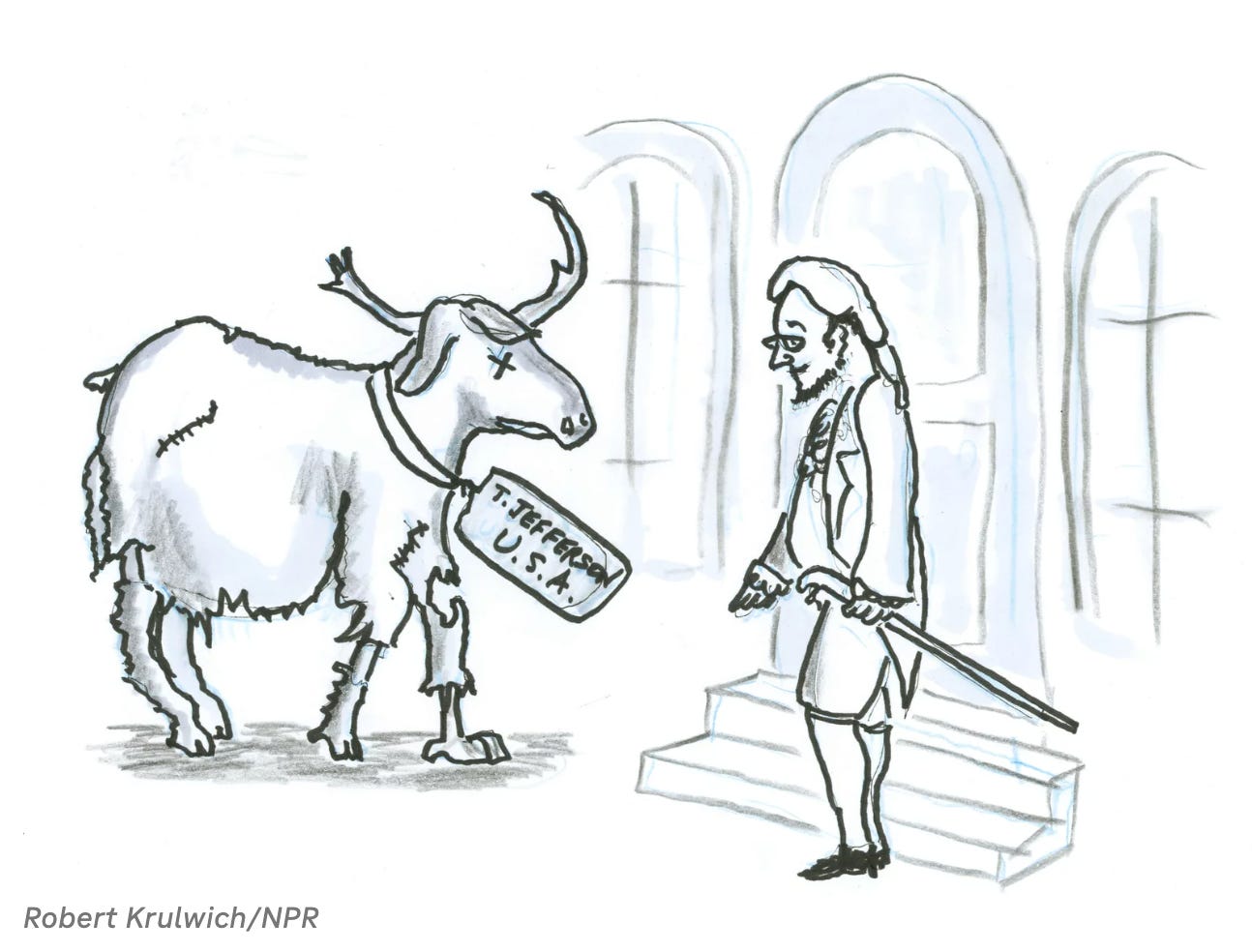

Jefferson refuted Buffon's claims, citing for example the American (black) bear at 412 pounds and the European bear at 153, the American beaver at 45 pounds and the European at 18. Jefferson's data do not bear close scrutiny (he listed the cow in America at 2,500 pounds and at 763 in Europe), but he had two trumps. The first was the North American moose, under the belly of which, he claimed (quite erroneously), a European reindeer could walk. …

Jefferson also thought he had the advantage with the example of the mastodon, which he claimed to be bigger by half than either the living elephants or the extinct Siberian mammoth. This might seem something of a cheat, but he genuinely believed that it was not extinct.

The woolly mammoth survived until 4,000 years ago on Baffin Island in the Canadian arctic. Today’s scientists blame its demise at that point on, you guessed it, climate change. Whatever did them in, it could not possibly have been the the fault of First Nations hunters.

As for Buffon's evidence of the degeneracy of American Indians, Jefferson refuted it in two ways. First, he used an eloquent speech by the "Shawanee" Chief Logan as an example of their civilization. This speech was later reproduced widely in Europe and very much admired. With respect to hair and sexual ardour (a subject that Europeans found titillating), Jefferson coolly pointed out that ". . . with them it is disgraceful to be hairy on the body. They therefore pluck the hair as fast as it appears." If Indians had smaller families than Europeans, it was through economic necessity. When Indian women married white men and were treated well, they produced large families, although it was true that women had a low place in Indian society. They were subjected to ". . . unjust drudgery. This I believe is the case in every barbarous people." …

A particularly delicate issue in the discussion of "degeneracy" concerned Europeans emigrating to North America. Buffon stopped short of saying that they also became inferior on American soil, but Abbé Raynal had no reservation claiming exactly that.

Buffon did, however, denigrate the intellectual achievements of Americans. This dismissal incensed Jefferson, who quite reasonably noted that in two hundred years, "in war we have produced a Washington . . . in physics we have produced a Franklin, than whom no one of the present age has made more important discoveries . . . “

Benjamin Franklin's own response to the issue of American degeneracy was typically pragmatic. At a dinner party in Paris where a number of Americans were present (and who, he noted, were quite tall) he asked them to rise, followed by the French, over whom they towered…. Franklin graciously noted that he himself was not so very tall.

… In Paris, Franklin had held many scientific discussions with Buffon and was the partial cause of the latter's change of mind. The conversation that had so profound an effect had been about population growth. In this area, Franklin's insights preceded those of Thomas Robert Malthus by 30 years. Buffon wrote, "because we know from the celebrated Franklin, that in twenty-eight years the population of Philadelphia (without immigration) doubled . . .

One chapter in my anthology Noticing is about what an enormous impact Franklin’s discovery that the American colonies were doubling in population every 20 or 25 years just from natural increase rather than from immigration made on European intellectuals, who had assumed that humanity tends to degenerate over time (like photocopies on a Xerox machine). That was a key fact in inspiring Darwin’s theory of natural selection.

in a country where the Europeans multiply so promptly, where the life of the natives is longer than previously, it is not possible that humans degenerate."…

So Jefferson decided to show him a full-grown American moose. He wrote to General John Sullivan, president (governor) of New Hampshire, for help in getting a large specimen, instructing him that the bones of the head and legs should be left in the skin so that it could be mounted in a life-like manner. Eventually a "seven-foot tall" moose was collected in Vermont and shipped to Paris.

The stuffed moose was in bad shape when it arrived in Paris, but so was Buffon who died probably before Jefferson got a chance to show it to him.

How long can the Pulitzers keep any reputation? The Time won the award in the 1930s for their lies about the Holdomor, won it in 2018 for their lies about the Russian collusion hoax and then won another prize for the moronic yet dangerous 1619 project.

I would be embarrassed to get a Pulitzer. Ar this point, I think the Stalin prize would be more prestigious.

No vibe shift at the Met Gala, which is honoring an exhibit called Superfine: Tailoring Black Style. Obviously this means the distinguished black guests have been displaying their penchant for restrained and elegant clothing with broad appeal…OK, I kid, it’s stereotypically garish and when it comes to the men it’s frankly pretty gay. It has literally no applicability to everyday wear unless we are talking about Billy Porter. LeBron begged off appearing because of injury, but I would honestly not be surprised if it’s because his advisors presented some designs from clothiers that wanted to dress him and it’s simply not masculine and would look especially ridiculous on his large frame. Naturally he is being criticized for his absence.