NYT: Calipers Are Cool Again!

Measuring skulls to do skull science is respectable as long as you are into Canine Biodiversity rather than Human Biodiversity.

One of the common obsessions of the 21st Century is an aversion to scientists measuring skulls. Calipers are the single most denounced scientific instrument of our age. The fact that lots of scientific institutions have skull collections drives modern media insane:

For example, from The Argument:

How the racist study of skulls gripped Victorian Britain’s scientists

Published: August 21, 2025 8:09am EDT

Elise Smith

Associate Professor in the History of Medicine, University of Warwick

The recent publication of the University of Edinburgh’s Review of Race and History has drawn attention to its “skull room”: a collection of 1,500 human craniums procured for study in the 19th century.

Craniometry, the study of skull measurements, was widely taught in medical schools across Britain, Europe, and the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, the harmful and racist foundations of craniometry have been discredited. It’s long been proven that the size and shape of the head have no bearing on mental and behavioural traits in either individuals or groups.

In the 19th and early 20th century, however, thousands of skulls were amassed to enable research and instruction in scientific racism. Edinburgh’s skull room is by no means unique.

Unlike phrenology, a popular theory which linked personality traits to bumps on the head, craniometry enjoyed widespread scientific support in the 19th century because it revolved around data collection and statistics.

Craniometrists measured skulls and averaged the results for different population groups. This data was used to classify people into races based on the size and shape of the head. Craniometrical evidence was used to explain why some peoples were supposedly more civilised and evolved than others.

The vast accumulation of data drawn from skulls appealed to Victorian scientists who believed in the objectivity of numbers. It equally helped to validate racial prejudice by suggesting that differences among peoples were innate and biologically determined.

The study of skulls was central to the development of 19th-century anthropology.

And developing a science is Bad, for reasons.

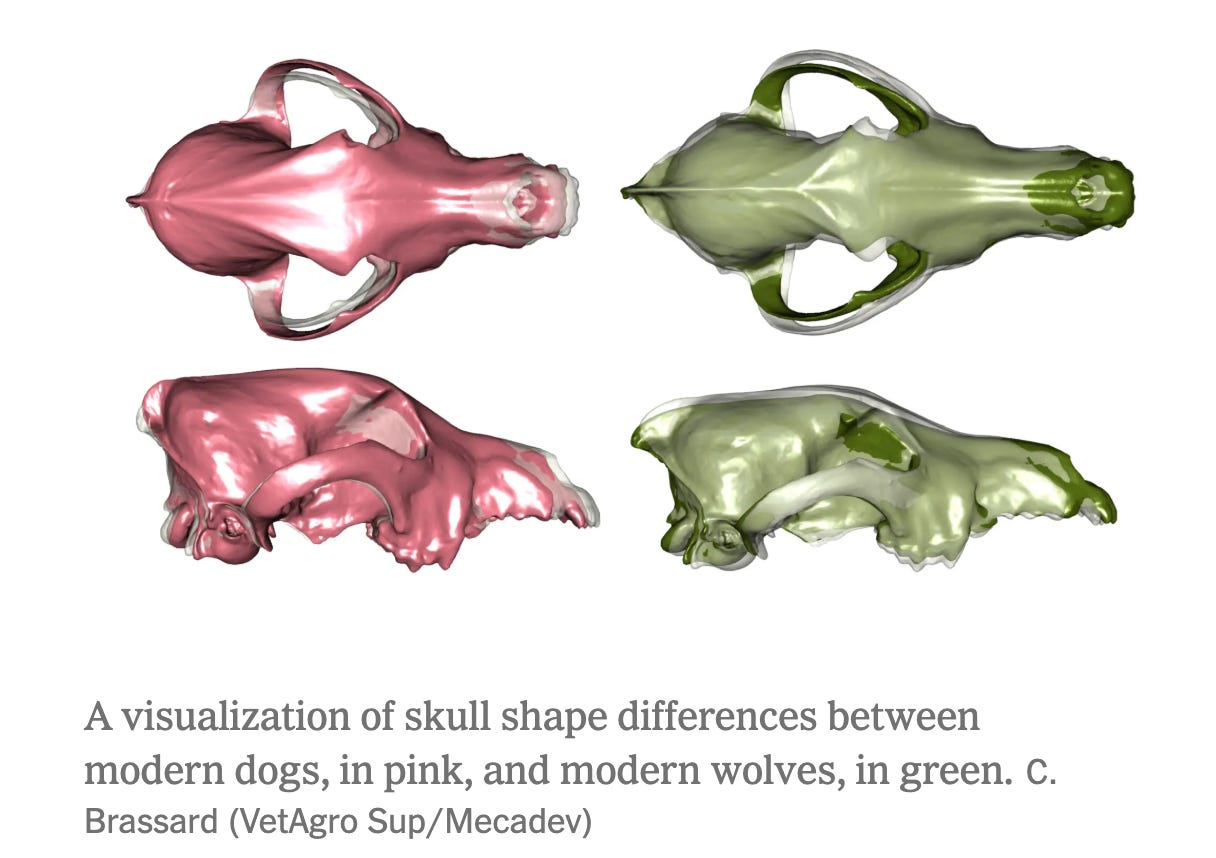

On the other hand, measuring canid skulls as opposed to human skulls is obviously Good Science. Thus, from the New York Times Science section:

The Dogs of 8,000 B.C. Were Amazingly Diverse

The staggering array of modern dog breeds is typically traced to the Victorian era. But half of all canine variation was in place roughly 10,000 years ago, a new study suggests.

The history of selective breeding is confusing because you can only see a broad, steady takeoff beginning in 18th Century England with pioneers like Robert Bakewell (1725-1795).

On the other hand, you can also see prodigious feats of selective breeding with individual life forms in the more distant past like the huge increases in the size of ears of corn in Mexico over the last 6,000 years. But despite individual triumphs, nobody seemed to learn much of general utility about breeding. Gwern wrote an essay about why scientific agriculture never really kicked into gear until the 1700s despite the huge interest in selective breeding.

By Emily Anthes

Nov. 13, 2025, 3:15 p.m. ET

As a species, dogs are mind-bogglingly diverse, encompassing animals as different as the Shih Tzu, the Shar Pei and the Shetland sheepdog.

This explosion of canine forms has typically been traced back to the Victorian era, when dog fanciers created a wide range of standardized breeds and began churning out canines that met such varied physical standards.

It’s striking how dog breed progress appears to have slowed down in recent generations.

Paywall here.