Paul Rudolph and the Fundamental Problem with Architects

What's wrong with architecture?

Paul Rudolph, once-celebrated architect of the leaky 1970 Tentacle Porn Brutalist Orange County (N.Y.) Government Center, was a hilariously awful real-life example of what happens when Ayn Rand’s Howard Roark is given free rein.

His career is worth being remembered as a cautionary tale of how elite taste can go very wrong. Rudolph’s now being given a retrospective at the Met. From the New York Times:

Paul Rudolph Was an Architectural Star. Now He’s a Cautionary Tale.

His Brutalist buildings, praised during the Kennedy era, are now being demolished. A new exhibition in Manhattan looks at the limits of genius.

By Michael Kimmelman

Oct. 16, 2024, 5:05 a.m. ET

American architecture’s bright, shining light of the Kennedy era, Paul Rudolph was scrounging for commissions less than a decade later. He may now be best remembered — to the extent his name rings bells — for the heroic, bush-hammered concrete Camelot he designed during the early 1960s to house the architecture school at Yale.

When it opened, it prompted rapturous reviews akin to what, many years later, greeted Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao. But the building soon became a piñata for everything wrong with modern architecture.

And Rudolph, who died at 78 in 1997, dropped down the memory chute. …

He was the jet age version of Ayn Rand’s Howard Roark. An epic bundle of contradictions, he cooked up phenomenal, visionary drawings and flamboyant, muscular buildings for occupants he made miserable by caring too little about how the buildings actually functioned.

Not everything Rudolph dreamed up got built:

… he repurposed Robert Moses’s lunatic plan to demolish a whole swath of downtown Manhattan and drive an elevated expressway through it. Commissioned in 1967 by the Ford Foundation, Rudolph’s conceptual drawings of the Lower Manhattan Expressway project plowed through the Lower East Side and SoHo to make room for a megastructure two miles long — an eye-popping concrete mountain range, stacking apartment pods, trains, people movers, garages and lanes of traffic between the Holland Tunnel and the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges.

That plan, amazing and appalling, never came to pass, thankfully, but in 1970 Rudolph took on a federally funded urban renewal project in New Haven, Conn., called Oriental Masonic Gardens. If America could land Apollo 11 on the moon, housing officials in the Nixon administration claimed, it could also solve the country’s housing crisis.

Rudolph’s fix involved plywood and prefab units, akin to shipping containers, organized across a 12-acre site in L-shaped configurations around shared courtyards. Vaulted roofs suggested the rippling silhouette of a hillside village.

The project looked pleasing on paper. Residents found it no better than a trailer park. Buildings leaked. Oriental Masonic Gardens closed a decade after it opened.

I don’t think it will come as a big surprise that Hollywood has staged various dystopian sci-fi films and scenes of family dysfunction in Rudolph buildings. The exhibition includes clips from “Brainstorm,” the ’80s horror-fantasy, showing Christopher Walken roaming Rudolph’s headquarters for Burroughs Wellcome, the pharmaceutical company in North Carolina.

Brainstorm is one of the more forgettable movies I’ve ever seen. All I can remember about it in 1983 is that it occurred to me while watching it that it should instead be a fake documentary. (And then right around then, you started seeing fake documentaries like Zelig and Spinal Tap, plus increased use of documentary-like elements in conventional feature films like Goodfellas. A good trend.)

From Wes Anderson’s movie “The Royal Tenenbaums,” we get the scene in Rudolph’s Beekman Place apartment where Ben Stiller’s anxious character stages a late-night fire drill to see how quickly his sleeping children can leap from their beds and navigate all of the apartment’s treacherous Escher-like Plexiglas and Mylar levels and stairs.

Not quickly enough, it turns out.

Rudolph was born in 1918 in Kentucky and, like Frank Lloyd Wright, was the son of an itinerant preacher. …

For Rudolph, “the age-old human needs” for “monumentality, symbolism, decoration and so on,” he wrote, “are among the architectural challenges that modern theory has brushed aside.”…

By the mid-60s, he was on the covers of Progressive Architecture and The New York Times Magazine, and posing for Vogue atop his behemoth Temple Street Parking Garage in New Haven. With its carved concrete vaults, stretching across two city blocks, the garage did for the automobile, Rudolph boasted, what the Roman Colosseum had done for chariots. Architects made pilgrimages to New Haven to see the future.

And of course to see Rudolph’s Art and Architecture Building at Yale, where he had become chairman of the architecture school.

A general rule of college campuses is that the ugliest structure on campus is the Art and Architecture Building, with Rudolph’s at Yale as perhaps the most famous example. Here’s part of Yale’s old campus:

And here’s Rudolph’s contribution to the ensemble:

The building’s corduroy facade arranged shadows and planes, solids and voids in a composition as dynamic as a Boccioni and as poised as a Mondrian. Inside was an atrium, with 37 levels subdividing seven stories.

“You couldn’t go to the men’s room without having a spatial experience,” was how the architect Joseph Esherick described the layout.

What I’ve always from the men’s room. I’m booking my ticket now!

Students found it impractical to the point of seeming sadistic. They protested. The building became a totem of ’60s unrest. Walls were defaced by graffiti. A fire, whose cause remains uncertain, ruined parts of the interior. …

But Rudolph catered to a niche audience, above all himself, and a wide public has never come around to his Brutalist aesthetics. A number of his buildings have suffered the wrecking ball in recent years, the Burroughs Wellcome headquarters among them. Also, his striking civic complex in Orange County, N.Y.,

It looks like it’s still there, more or less.

a housing development in Buffalo and a high school in Florida.

These losses have rightly alarmed preservationists. Buildings are not sculptures; they need to function for the people who use them. But the most ambitious of these buildings, over time, become society’s heritage and responsibility. It’s worth remembering that the bulk of Rudolph’s work is now as old as McKim, Mead & White’s Penn Station was when it was destroyed, giving rise to our modern landmark laws.

Vietnam, the failures of urban renewal and other upheavals of the ’60s precipitated Rudolph’s reversal of fortunes. His Great White Man vision of architecture came to represent The Establishment. Figures like Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown were touting the virtues of billboards, suburbia and the Las Vegas Strip. A new generation, looking to rebrand architecture, was devising winking historical pastiches. Rudolph’s super-serious megastructures seemed like dinosaurs.

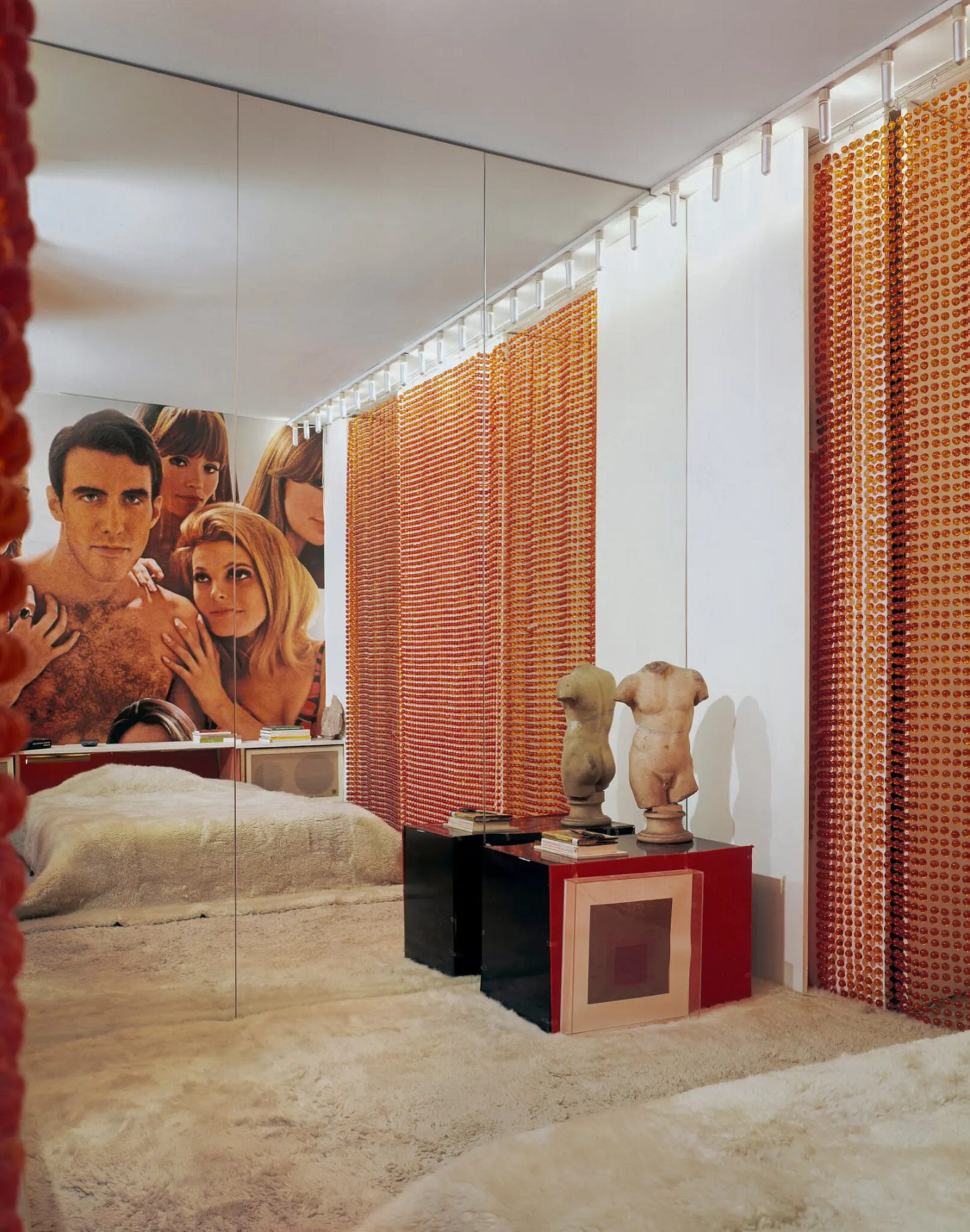

… we catch a glimpse of the louche and sensual Rudolph whose mirrored bedroom, with its furry white bedspread, white shag carpet and billboard-size reproduction of a cologne ad, was famously photographed by Ezra Stoller.

An architect friend of mine worked for Rudolph for a little while many years ago. He did not find it a fulfilling or pleasant experience. Brutalism wasn’t just an aesthetic for Rudolph, it was a lifestyle. My friend said that Rudolph, a gay sadomasochist, enjoyed inflicting psychological torture on his employees almost as much as he enjoyed inflicting physical torture in his off hours.

A basic problem with architecture is that most of its best possible design innovations have already been dreamed up over the last 10,000 years. So, the job demands a fairly humble personality who sees his task as reusing humanity’s immense achievements in architecture in a skillful way.

After all, buildings last, hopefully, a long time. And they are looked at, involuntarily, by huge numbers of people. If you are a fashion designer and design some ugly new clothes, well, they’ll stop being worn pretty quickly. But ugly buildings endure … except in the case of quite a few of Rudolph’s, that tended to have problems that other architects had solved long ago, like leakiness.

So, in architecture, it’s best to lean toward the tried and true.

But, architecture tends to attract megalomaniacal personalities like Rudolph.

Artistic "geniuses" have done a lot of harm. They seem to forget that they're public servants. You're not making a monument to your stupid ego; you're making a product for the public.

For those unfamiliar with New York geography, Orange County is not some backwater; it is literally two counties up the river from NYC, albeit on the west side of the Hudson. It has a population of over 401,000 (the 7th highest in NY outside of NYC) and is home to West Point. One can easily take a train from Tuxedo to Hoboken in 55 minutes.