Raymond Chandler

Suggestions for my upcoming podcast requested.

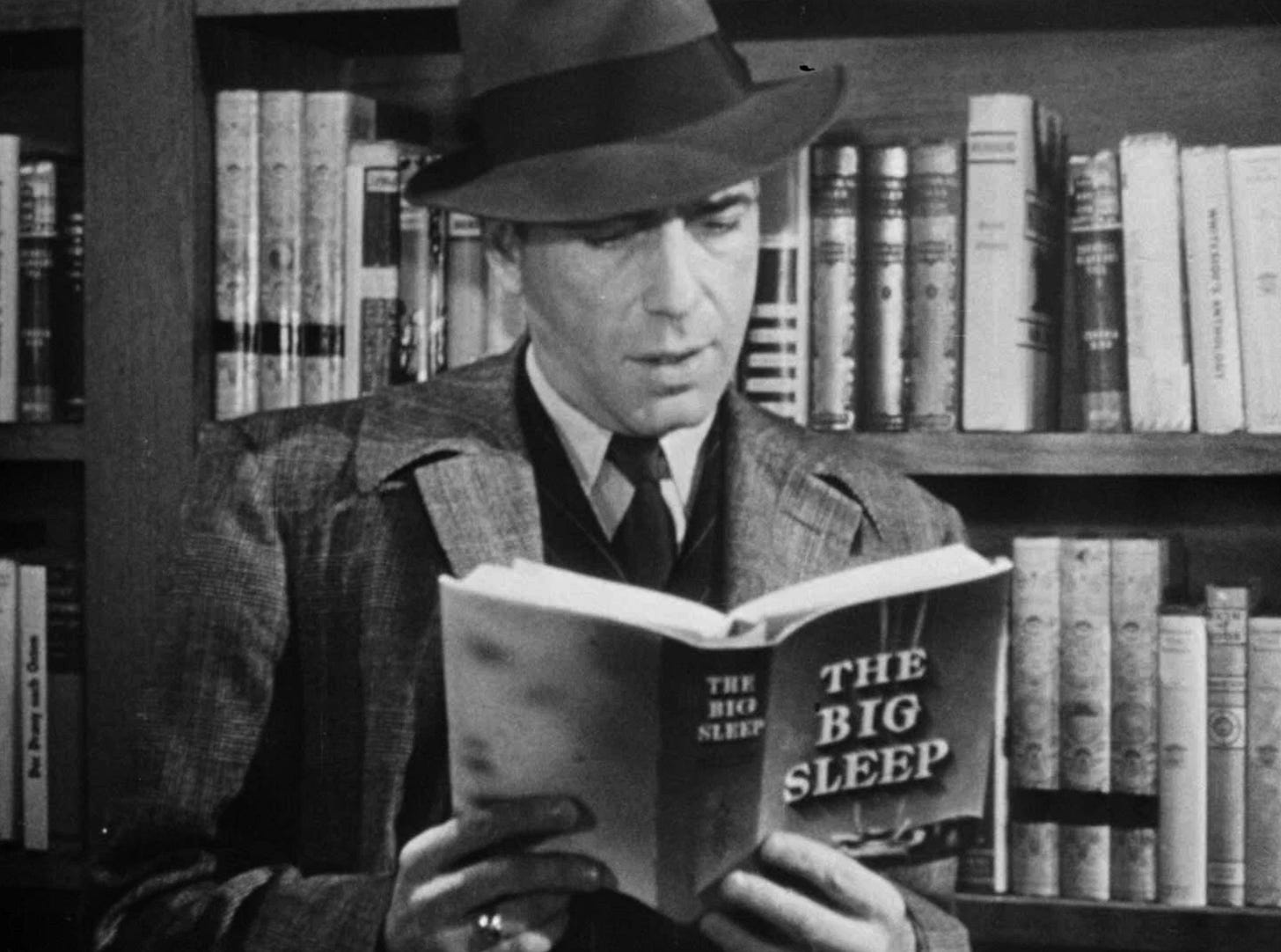

I’m doing a podcast this week in which I’m supposed to offer literary insights on the oeuvre of Raymond Chandler, author of the Philip Marlowe Los Angeles noir detective novels.

What are some topics I ought to bring up?

Offhand, I can think of:

Marlowe’s Englishness.

World War I.

His real life relationship with the plot of There Will Be Blood.

Black and white noir vs. color noir movies?

How carefully should novelists hoping to sell their works to Hollywood describe their heroes’s physiognomy?

Marlow, Hammett, and Cain.

What was Los Angeles like in 1940?

The big change in Marlowe’s style between The Big Sleep and Farewell My Lovely vs. The Long Goodbye.

What else is interesting about Raymond Chandler?

It's Long Goodbye, not Last Goodbye. After that there is Playback, which he finished, and Poodle Springs, which he did not.

One interesting thing is how uninterested in plot he was. Chandler himself said, I think in a letter, that he didn't care about plot; the only reason to write, the only thing enduring about any writing, is style. His letters are awesome by the way.

The only one of his novels that really has a good plot is Farewell My Lovely because of the twist ending (the same twist is reused in Long Goodbye). There is a famous story of Howard Hawks shooting Big Sleep and halfway through he realizes that they don't know who killed the chauffer and he can't find the reveal in the script, so he has someone reread the book and they can't find the answer either, so he telegrams Chandler who is travelling, WHO KILLED CHAUFFER? to which Chandler responds HAVE NO IDEA. Or something like that.

You could compare Marlowe to Sam Spade. Spade consistently gets the better of everyone whereas Marlowe is always getting ambushed and beaten up. Hammett said that Spade was not based on a real detective; he is a composite of the self-image of the awesome tough guy that all the real detectives Hammett worked with at Pinkerton's thought they were and/or wanted to be. Sensitive, intellectual, loner, chess-playing Marlowe is clearly Chandler himself.

The contrast between Chandler and Hammet is also interesting. Hammett's books are kind of out there, borderline fantastic at times. Chandler's are much more grounded, more realistic. They also move more slowly.

Chandler really invented LA noir, which is a genre that is still going. The main reason was simply because he lived there, but he came to love the contrast between the sunny exterior and the (supposedly) sordid interior.

You could also mention his much older wife (18 years) and how she misled him about her age, and then when he figured it out, he misled everyone else. He started to spiral after she died.

You could mention his screenwriting, of which the best was Double Indemnity. He never wrote the screenplays of his own books but wrote or contributed to others. There is another story, I think about Blue Dahlia but I might be off, that he had a horrible case of writer's block and couldn't finish and they were way behind schedule and losing money, and so he proposed to the producer or director that he finish it drunk. Approval secured, he did just that.

The Black Dahlia is of course the second-most famous LA murder case of all time, which happened a year after that film and was named for it. It inspired the career of James Ellroy and remains, as far as I know, unsolved. Sort of California's Jack the Ripper case.

Finally, as I am sure you know, "Bay City" is really Santa Monica and was apparently notoriously corrupt back then. The person who first gave me a copy of Chandler around 1994 was a multigeneration Angeleno whose father was LAPD and he said everyone knew Santa Monica was a snake pit then. I'm not sure when it turned around.

Hmm, a lot of comments already captured what I would have to say, but as a lifelong mystery fan, constant mystery reader, and regular patron of Otto Penzler's Mysterious Bookshop, I'd add: Although he's associated with noir, his real contribution to the genre was its romantic side. The toughness came from its early progenitors like Hammett and Carrol John Daly and their imitators, but Chandler made it beautifully tragic rather than ironic and tough. All mystery fans know the Golden Age of crime writing started in 1920 with the first Poirot, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, and ended roughly around the war, so Chandler was late--late in life to publish his first novel, and late to enter the golden age. In that way he was rare in a creative genre, to be a late entrant who revolutionizes it. All of his novels except 2 were based on short stories he'd written for the pulps in the 30s, like Woolrich, who also flourished in the pulps before turning to novels. And also like Woolrich, whose alcoholic, mother-obsessed life mirrored Chandler's in many ways, the 30s pulps were his most creatively fertile period. But once those took a huge economic hit during the war due to men being overseas, paper restrictions, and a crackdown on their material (Fiorello LaGuardia waged a campaign to have the horror pulps removed from newsstands) and with the rise of the paperback, Chandler and Woolrich managed to transition while many pulp authors didn't. How? For Chandler it was, unquestionably, his beautiful prose: the thing that elevates his novels above 99% of other crime fiction past and present, which today still strikes the ear as fresh and clever, completely unique, and something every "tough" writer still tries to imitate. His plotting was a mess--even Faulkner couldn't figure out who killed the chauffeur in the Big Sleep, famously--so if you want the best plotting ever go read Hammett's The Glass Key, the process of which devising literally almost killed him. And if you want toughness go read Spillane. And heartlessness, read Thompson. Even Chandler's characters were nothing special. But his prose! Like the aesthete who comes to write about the battle after the soldiers have bled and died, he came to save the crime genre by transcending it through beauty. Whereas most crime writers had the plain language of Mark, Chandler had the poetry of Luke. No one can write about Los Angeles without either embracing him or consciously running away from him. New York and Chicago had no similar champion to distill their essence the way he did; the way the Romans had. He was an aesthete in a masculine man's genre, and he got it right. "It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window."