Sir Tom Stoppard, RIP

Did the great playwright, author of "Arcadia," ever have anything to do with Jeffrey Epstein? And much else about Sir Tom ...

Sir Tom Stoppard, the leading English-language playwright of the last third of the 20th Century and the most dedicated anti-Communist among the great creative writers in the Anglo-American world during the Cold War, has died at 88.

The whole world, or at least its higher brow segments, have been rushing to praise Stoppard, my favorite playwright.

So out of sheer bloodymindedness, I’ve decided to look into whether there was any connection between Stoppard and Jeffrey Epstein. I’ll provide the answer way below.

I’ve written a lot about Stoppard over the years, so below are three essays about him for Taki’s Magazine, along with some new material as I think of it on subjects like Stoppard’s decade and a half on staff as a script doctor for Steven Spielberg.

Here’s my review of his biography and last (?) play in Taki’s Magazine:

April 07, 2021

The English stage’s second Elizabethan Age might not compare to its first, but it’s been nothing to be ashamed of. And Sir Tom Stoppard has been the closest to its Shakespeare. Strikingly, of all the major English-language authors of the later 20th century, Stoppard was the most dedicated anti-Communist.

While many top writers born in the 1930s, such as Tom Wolfe and John Updike, were conservatives of one sort or another, Stoppard, who was born in Czechoslovakia in 1937, wrote as many works against Soviet tyranny as perhaps all the other big names combined.

Philip Roth, a liberal Democrat, was perhaps the second best friend of dissident writers behind the Iron Curtain. While Stoppard introduced the West to Vaclav Havel, Roth introduced us to Milan Kundera.

With the publication of Hermione Lee’s authorized biography Tom Stoppard: A Life and the announced resumption in London this June of Stoppard’s 2020 play Leopoldstadt, a fictionalized family album of his ancestors, it’s timely to consider whether Stoppard’s extraordinary lack of awareness of his Jewish ancestry until he got in touch with a cousin from the Old Country in 1993 was relevant to his anti-Marxism.

His family fled Czechoslovakia during the Nazi invasion in March 1939 to Singapore. Then his doctor father died at the hands of the Japanese invaders in 1942. But after he and his widowed mother arrived in England in 1946 with her new husband, who had been a major in the British Army, Stoppard enjoyed a life of near-constant achievement, admiration, and honors. Hence, his biography, while immensely informative, is lacking in dramatic tension.

After an early childhood as a refugee in Asia, England, even in 1946, seemed like paradise to young Tom. By nature a loyalist, he instantly became an unabashed English patriot. As Leonard Chamberlain, Stoppard’s autobiographical stand-in in Leopoldstadt, declares:

to what’s left of his once huge Jewish extended family in Vienna who have survived unimaginable horrors during the Holocaust while he, personally, was off in England growing up to be Bertie Wooster (or, at least, P.G. Wodehouse) and damn glad of it:

I’m proud to be British, to belong to a nation which is looked up to for…you know…fair play, and parliament, and freedom of everything, asylum for exiles and refugees, the Royal Navy, the royal family…. Oh, I forgot Shakespeare.

After a modestly expensive boarding school education, Stopped skipped university to become a newspaper reporter in his hometown of Bristol. This might seem like a provincial dead end, but the Bristol Old Vic theater was headlined by a pre–Lawrence of Arabia Peter O’Toole (who stole the heart of the woman Stoppard adored).

Soon, Stoppard was off for London, with beginner plays running here or there. By 1967, his Hamlet–meets–Waiting for Godot metaplay Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead was a historic sensation. His anti-left philosophic comedy Jumpers was a hit in 1972 and Travesties a smash in 1974. In response to criticism that his plays were longer on intellect than emotion, he premiered the accessible romantic drama The Real Thing in 1982.

When his spy thriller about quantum mechanics, Hapgood, proved incomprehensible to audiences in the late 1980s, he doubled down on the science in his chaos-theory-themed Arcadia of 1993, which was first inspired, implausibly enough, by James Gleick’s obituary for physicist Richard Feynman. It proved a thing of beauty, perhaps the greatest play in English since Long Day’s Journey Into Night.

After numerous flops as a hired-gun screenwriter (the best being Brazil for Terry Gilliam and Empire of the Sun for Steven Spielberg), he wrote the hit movie Shakespeare in Love, which beat his frequent employer Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan for Best Picture.

Stoppard explained that he took on so much outside work because it took him about a year to write each one of his plays, but he only came up with an idea worth spending a year writing a play about every three or four years.

So, in the meantime he’d do things like hire translators to translate plays from German and Czech by once famous older writers who’d fallen out of fashion in the English-speaking world like Arthur Schnitzler or living playwrights behind the Iron Curtain like Vaclav Havel, and then punch up the translations for West End audiences.

Stoppard had a hand in a huge number of commercial movie screenplays, but only got his name on a fraction of them (perhaps for the good of is reputation).

Terry Gilliam’s Brazil is slightly overstuffed with brilliant ideas from multiple writers, but I’m guessing that Stoppard supplied its core notion: What if 1984 had been written not by disillusioned leftist George Orwell but by Orwell’s reactionary doppelganger Evelyn Waugh? Back in the 1980s, Stoppard had declared that his three favorite writers were Waugh, Iron Curtain exile Vladimir Nabokov, and the ultra-British Thomas Babington Macaulay.

Lee’s biography makes clear that Stoppard was paid a retainer by Spielberg for about 15 years from the 1980s into the 1990s to be an uncredited staff script doctor for Spielberg, and that he had something to do with every Spielberg movie during that stretch.

Stoppard had his least involvement with Spielberg’s masterful Schindler’s List. He provided only two services to that film. As when Ben Hecht was hired to write a fourth screenplay of Gone With the Wind, but told David O. Selznick and Victor Fleming that the first attempt by Sidney Howard, who had since died, was as perfect as a mortal human could do at condensing that huge novel into a single comprehensible movie, Stoppard’s main service to Schindler’s List was turning down Spielberg’s invitation to rewrite Steven Zaillian’s first draft because, Stoppard told Spielberg, Zaillian’s script was great.

But then, during filming, a catastrophic flaw in the plot was discovered that would seemingly require halting production to rewrite most of the screenplay and junking much of the footage already shot. In desperation, the film crew resolved to call Sir Tom, a famously clever chap, to see if he could think of anything to do in the crisis. Stoppard called back the next morning and pointed out that if they refilmed a single shot with one line of dialogue changed from Zaillian’s words to the alternative line he’d invented overnight, everything would be fine and they could carry on.

Not every Spielberg movie that Stoppard did uncredited work upon was as good as Schindler’s List. For instance, Stoppard wrote much of Spielberg’s 1989 movie Always with Richard Dreyfuss, Holly Hunter, and John Goodman as pilots of water bombers fighting forest fires. I quite liked it, but Always is about as forgotten as a Spielberg movie can get.

Stoppard got his name on Empire of the Sun, which has always been one of my favorite Spielberg movies, in part because Spielberg made it a visual tribute to some of Stoppard’s early obsessions in the theater, such as in After Magritte presenting the audience with seemingly surrealist incomprehensible tableaus that a baffled police inspector tries to figure out.

Similarly, Empire of the Sun features stunning scenes in a Japanese interment camp for British civilians in Hong Kong during WWII that initially baffle the audience until they figure out that incredible-looking things like this really did happen in 1945.

Stoppard said that he didn’t write the most whiplash sequence in Empire of the Sun — the one that begins with young Christian Bale saluting the three Japanese pilots — but that Spielberg came up with it:

Still, Stoppard was a lot better playwright than screenwriter. He really wasn’t that interested in movies.

For example, he only directed one film, his 1990 adaptation of his Rosencrantz & Guildenstern, which turned out like Bill & Ted’s Bogus Tragedie.

Stoppard got terrific performances out of Richard Dreyfuss, Tim Roth, and, especially, Gary Oldman as, in effect, Keanu Reeves wandering in from Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. (Keanu and Alex Winter are currently appearing in Waiting for Godot, the other play Stoppard spoofs in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.)

His movie’s set design for Elsinore Castle reflected Stoppard’s turn toward science in the later 1980s: it looks like Tycho Brahe’s astronomical observatory. Rosenkrantz and Gyldenstierne were real life cousins of Tycho, who had visited London in 1589. And astronomy is indeed one of the vast number of subjects that Hamlet touches upon: “O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.”

On the other hand, Stoppard’s shortcomings as a movie director were immediately visible upon screening the dailies after the first day of shooting. Sir Tom was quite pleased with his first-ever footage, but his financial backers were alarmed that Stoppard had placed his camera in the equivalent of the best seat in the house, say, 6th row center, and just left it there all day long while Oldman and Roth flipped coins.

The producers politely brought to the great man’s attention that, unlike in theater, it is customary in cinema to move the camera around. Stoppard eventually agreed to let his cameraman from then on do all that boring motion picture stuff involving pointing the camera and deciding when to have a close-up, while he concentrated on the interesting work involving the actors’ line readings.

But these numerous high points of his career haven’t exactly been dramatic comebacks because he’s never been down-and-out. He’s always been in much demand by the talented and well funded.

Lee’s biography makes clear how much work it is to be a great playwright. Whenever Sir Tom meets the Queen, she asks him her all-purpose greeting: “Busy as ever?” In Stoppard’s case, his “Yes” is always true. The only thing that appears to have slowed down Stoppard’s career was the end of transatlantic Concorde flights.

Stoppard has always been recognized as a superior example of a human being. He’s superbly thoughtful, benevolent, and well-mannered. Even when he’s cut corners—most notably in swiping Arcadia’s central plot device of slightly pathetic 20th-century publish-or-perish academics trying to research great-souled 19th-century figures from A.S. Byatt’s fine 1990 novel Possession—nobody much minds.

This has helped Stoppard survive and thrive in a profession that is deeply suspicious of his conservative political instincts.

In an era when everybody else was obsessing over the long-gone threat of Nazi Germany, Stoppard was speaking up against the Warsaw Pact. Stoppard’s anti-Soviet plays include:

—Travesties, 1974, in which Lenin is the heavy.

—Every Good Boy Deserves Favor, 1977, in which a dissident is incarcerated in a Soviet mental hospital along with a genuine lunatic who, like the audience, hears a symphony orchestra at all times.

—Professional Foul, 1977, in which English moral philosophers visiting Prague for a conference must decide whether it’s moral to refuse to sneak out a banished grad student’s dissertation.

—Dogg’s Hamlet, Cahoot’s Macbeth, 1979, in which, among much else, Czech dissenters canceled from their theater jobs put on Shakespeare in a living room.

—Squaring the Circle, 1984, in which the history of Solidarity in Poland is recounted.

—Rock ‘n’ Roll, 2006, which is inspired by Stoppard’s alter ego, the playwright, prisoner of conscience, and president of the Czech Republic, Vaclav Havel.

In 1999, Stoppard published an article entitled “On Turning Out to Be Jewish” in Tina Brown’s short-lived Talk magazine. He explained that his mother, out of regard for her second husband’s feelings, had never wanted to talk about her first husband, and that she had brushed off her sons’ question of “Are we Jewish?” with talk of how nobody in her family cared about religion. (Stoppard himself is a praying man.)

So he grew up thinking he was a little Jewish, but not all that much, and generally not thinking much about his ancestors at all. Finally, in 1993, a cousin informed him to his surprise that all four of his grandparents had died in Nazi camps.

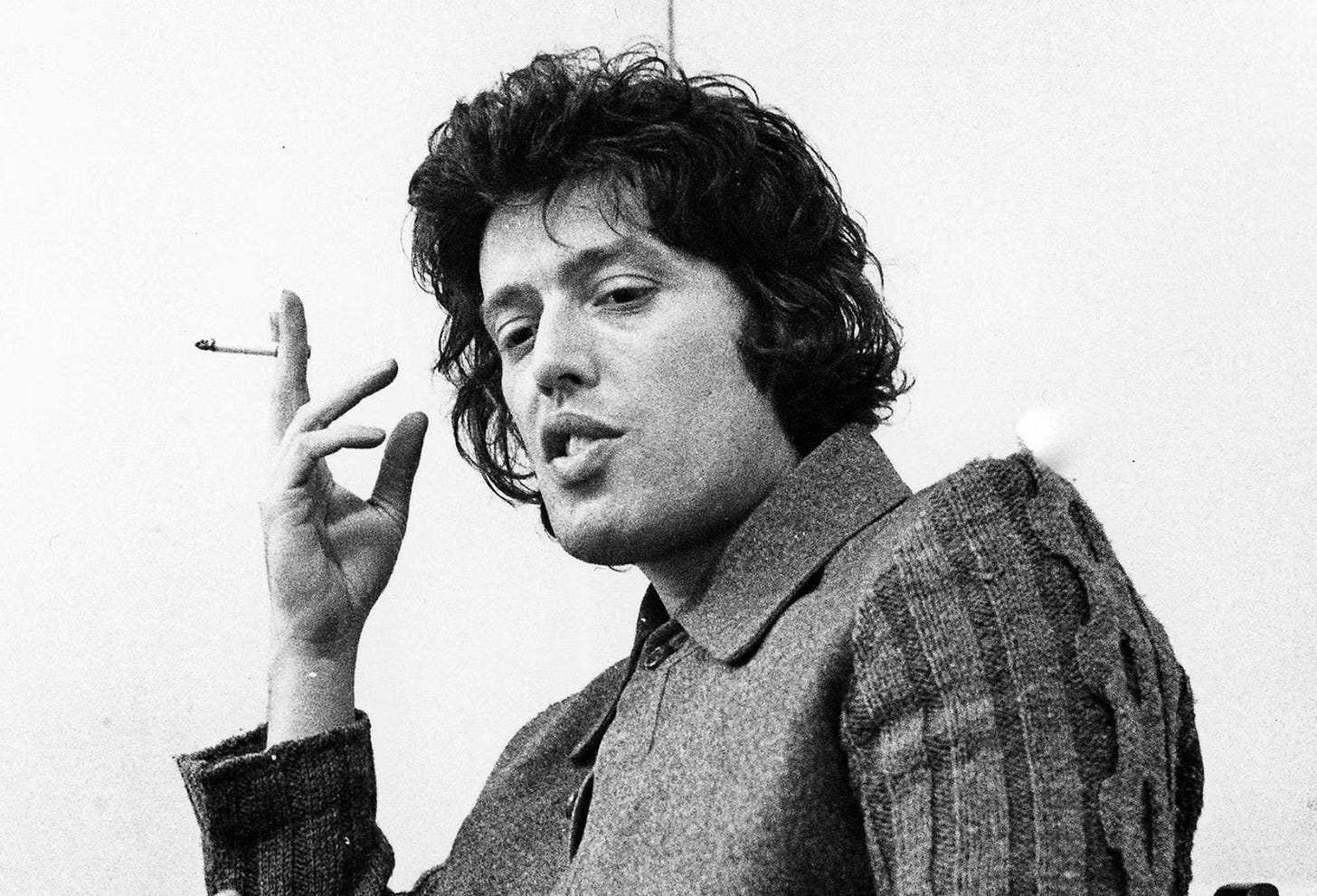

One reason that Stoppard didn’t wonder much about how Jewish he might be is that while he is an unusual-looking man, he’s not particularly Jewish-looking. He looks instead like a Rolling Stone, a cross between his friend Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts.

Another is that his parents were Czech nationalists who were proud citizens of the new republic that emerged out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after WWI. Stoppard denies any fealty toward the Czech people, but he’s the kind of conservative who can’t help being loyal.

Is Stoppard telling the truth about not realizing how Jewish he was? After all, he is one of the great creative artists of the age, a magician of misdirection. But his older brother, a prosaic accountant who has minded his money for decades, says the same thing.

I think it’s not implausible for boys, even a hyperintelligent one such as Stoppard, to not be alert to family history. For example, when I was 21, my best friend told me he had just been watching TV with his mother (a Katharine Hepburn look-alike), when she said, “That actor looks just like Frank.”

“Who is Frank?”

“Oh…I guess I never mentioned that I was married before.”

My friend then slowly extracted from his mother that she was sitting in a bar in New York in 1946 with her husband, Frank, when “your father,” just back from D-Day, swaggered up and asked her what a classy dame like her was doing with a loser like him.

So I told my mother this scandalous story while we were washing dishes. She replied, “That reminds me, I never told you. I was married before too.”

Her story, however, turned out to be less salacious: She showed me her first husband’s medal, awarded posthumously after he died in combat on Iwo Jima.

But I should have guessed something like that years before, because that finally explained why I had a third set of relatives besides my mother’s family and my father’s family. We went to Big Bear Lake every couple of months with a family whom I addressed as “Uncle Chuck” and “Aunt Betty” but who, my mother had informed me, weren’t exactly my relatives. But I had never been interested enough in family relationships to ask what that meant.

It turned out that they were my mom’s late husband’s extended family, whom my mother had lived with when he had enlisted in the Marines. Yet, up through age 21 I not only hadn’t figured that out, but it hadn’t occurred to me to even ask what exactly was our relationship to our quasi-relatives.

At least in the English-speaking world, family trees are not of intense interest to boys. And Stoppard has been an impressively boyish man throughout his long life.

On the other hand, as they get older, men often take up an interest in genealogy. Hence, Stoppard in his 80s has now finally written a play inspired by his relatives, although the fictional extended family he portrays from 1899 to 1955 is grander than his own, more like the mixed Jewish and Christian Wittgenstein family of Vienna. (As Stoppard has aged, he’s become less exclusively English by culture and more of a Mitteleuropean writer in the mode of Schnitzler and Zweig.)

The Holocaust is probably the most well-documented event in human history, so Leopoldstadt in 2021 is less fresh than his anti-Soviet plays of the 1970s–80s. But it’s a solid Stoppard play, which is a fine thing to be.

Like most of Sir Tom’s works, the first scene is intended to baffle the audience (although this time not with intellectual concepts but with the abundance of relatives on stage), while the rest of the play then rebuilds viewers’ confidence that they can figure out what’s going on, finally leaving them feeling smarter than when they came in.

But, as always with Stoppard, it helps to read the published script before seeing the play. Hence my margin note on the third page of the book reads, “This play needs a family tree.” But Stoppard, of course, had thought that through: Thus on the third-from-last-page of Leopoldstadt, one of the cousins indeed presents to the Stoppard stand-in his family tree.

In the 45 years I’ve been reading Sir Tom’s work, he’s always been a step ahead of me.

Here’s my 2015 review of his play The Hard Problem:

Steve Sailer

December 30, 2015

Tom Stoppard

As a Christmas present, I received the book version of The Hard Problem, the latest play by Sir Tom Stoppard. It’s the great Tory playwright’s first new work for the stage since his Rock ‘n’ Roll in 2006.

Granted, it’s perfectly reasonable to complain that a playwright who is best enjoyed in two stages — first reading the book at home, then watching the play in the theater — is too much work for what is supposed to be a relaxing evening out. Still, Stoppard has been an ornament of our civilization for a half century (his Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead debuted in 1966), and he works awfully hard to make his plays as simple as possible. (But, as Einstein said, no simpler.)

I’ve been reading Stoppard’s plays for forty years now. Despite the new work’s seemingly foreboding highbrow subject matter — the title refers to the “hard problem of consciousness” formulated by philosopher David Chalmers — this may be the most lucid and serene of all of Stoppard’s works. It’s not as ambitious or as emotionally resonant as Stoppard’s 1993 masterpiece Arcadia, but then what play is? Nonetheless, it offers the most straightforward introduction to Stoppard’s work since his 1982 romantic dramedy The Real Thing, which preceded his turn toward science as subject matter in the late 1980s.

The bickering neurobiologists of The Hard Problem return to the moral philosophy questions — Does God exist? What is virtue? How can free will be reconciled with the study of nature and nurture? Can altruism exist without consciousness? — that were argued with such manic wit by rival academic philosophers in his 1972 farce Jumpers.

That was the play that cemented Stoppard’s reputation for almost inhuman cleverness. It took Stoppard a couple of decades to live down the impression generated by Jumpers and Travesties (an amazing 1974 anti-Marxist comedy with Lenin as the heel) of having more head than heart.

Among the major writers of our time, Stoppard may take criticism more seriously than anybody else (in part because as a playwright he has actors financially dependent upon the popularity of his work; in part because the author, who is perhaps the world’s most reasonable man, can put himself in other people’s shoes so well). Thus, the prodigy’s career has proved remarkably enduring.

Interestingly, Stoppard’s views on God (he thinks He sounds more plausible than the alternatives) and mother love (a virtue, not just an instinct) don’t seem to have changed much since 1972.

As in Arcadia, where his heroine was modeled on Lord Byron’s daughter Ada Lovelace, the legendary 19th-century computer-programming theorist, Stoppard assumes that a lovely ingenue who is also a scientific prodigy is a winsome combination on stage.

I’ve suspected since Arcadia that one of Stoppard’s regrets in life is that he hasn’t had a daughter. On the other hand, he is not the kind of man to dwell on what luck he’s lacked because Stoppard, who was born Tomáš Sträussler in Czechoslovakia in 1937, is grateful for all the good luck he’s enjoyed since his widowed Jewish mother married a British Army major in a refugee camp in Asia. Upon arrival in his stepfather’s homeland after a hellish early childhood during WWII, Stoppard immediately became a patriotic English boy.

A natural loyalist, Stoppard became an enthusiast not only of his adoptive country, but of his Slavic homeland. He was one of the very few English-language literary figures to be actively concerned about Communist rule, writing at least ten original plays protesting the subjugation of Eastern Europe.

Among the things that have changed since Jumpers is that Stoppard’s tone is mellower and his stage tricks are less attention-seeking.

The ideological landscape has altered as well. In Jumpers, the left was dominant, plaguing the hapless protagonist, a traditionalist moral philosopher. In The Hard Problem, set in England in the first decade of the new century, his similarly old-fashioned heroine is beset instead by the self-confidence of her neo-Darwinian colleagues. The left is intellectually nugatory, and all the energy resides with the disciples of the late biologist William D. Hamilton, such as Richard Dawkins and Matt Ridley. Stoppard explains that the play grew out of an argument he started with Dawkins over his 1976 book The Selfish Gene.

Indeed, the two young men the heroine strives to out-argue sound rather like my pals at the classic blog Gene Expression circa 2005. In his “Author’s Note,” Stoppard cites Imperial College evolutionary biologist Armand Marie Leroi, an expert on human genetic variety, as his chief guide to the science. (Here’s Razib’s interview with Dr. Leroi at GNXP ten years ago.)

This surprisingly short play references a remarkable number of concepts utilized by 21st-century right-of-center intellectuals — the story opens, for example, with the heroine’s tutor explaining the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the standard introduction to theories of how altruism could evolve.

Other longtime fascinations of the Edge.org crowd featured in The Hard Problem are the replication crisis in psychology, the larger implications of the financial crisis of 2008, and adoption.

That got me interested in whether Stoppard ever met Jeffrey Epstein, since they were both big fans of science.

Paywall here.