The Decline of the Adventuress

Real life is still full of gossip-worthy adventuresses sleeping their way to the top, but novels and TV shows? Not so much anymore.

There has been much speculation over the reasons for the decline of the significance of the novel in our culture.

One reason is of course simply because we are richer and more technologically advanced, so we might as well watch stories told in film or TV versions rather than do the work of making up the picture in our heads.

For example, I recently picked up William Styron’s acclaimed novel Sophie’s Choice. It was quite good, but after 100 pages or so, I put it down rather than spend another ten or twenty hours finishing it. If I was that fascinated with the story, I’d be better off spending three hours watching the equally acclaimed movie version, with its famous acting performances by Meryl Streep and Kevin Kline. After all, Streep and Kline are better at reciting Styron’s dialogue on camera than I am at imagining the line readings in my own head.

Another reason is the growing feminization of fiction as males lose interest in reading stories about other guys, when they could be the hero of their own shoot-em-up video games.

Finally, ever-increasing segments of humanity have managed to get themselves increasingly off-limits for being portrayed without appropriate reverence in fiction or even TV commercials.

For example, consider the decline of that once popular character: the adventuress, such as Becky Sharp in Vanity Fair, Scarlett O’Hara in Gone With the Wind, or the real-life Lola Montez.

Nowadays, the mere word “adventuress” is considered in “dated” poor taste.

Spellcheckers now seldom recognize the plural “adventuresses” and try to change it to “adventurous:” e.g. Amelia Earhart or Sally Ride are considered appropriate roles models, and are taking over the word “adventuress,” but Wallis Simpson or Pamela Harriman are best forgotten.

If you are wondering, an “adventuress” would be the main female character of a story primarily aimed at women, while a “femme fatale” is in a story with a male protagonist. Hollywood movies used to abound in memorable femme fatales from Double Indemnity up through 1994’s The Last Seduction. But lately, 2014’s Gone Girl is a rare example.

One reason is because you aren’t supposed to tell fictional stories these days about members of Official Victim Groups, like women, doing bad things. (You can still spread gossip, of course, about real adventuresses, but don’t expect to get too much institutional backing for your novel or movie about one.)

This doesn’t mean that adventuresses have disappeared from real life. For example, for years I’ve been following in the gossip columns the further adventures of one of the all-time greats.

All this came to mind from reading the following book review in the Washington Post, which sounds like a remarkably boring version of a roman a clef about the actual world-class old-fashioned adventuress whose identity I will reveal and whose story I will tell after the paywall.

But this new novel is less about the Asian immigrant’s machinations to climb the social ladder in America than about rich white people’s racist and sexist microaggressions toward her.

Kathy Wang’s novel is an antidote for our global dissatisfaction

“The Satisfaction Café” is an upper crust satire about a woman who wonders if there could be a way to create more happiness in life.

June 20, 2025

Review by Ron Charles

On the first page of “The Satisfaction Café,” Kathy Wang writes, “Joan had not thought she would stab her husband.”

I’ve just met Joan, but I already like her spontaneous style. And it turns out, she’s not really such a menace to civil society — or even to husbands. But don’t push her too far.

Joan, the heroine of Wang’s winsome third novel, is a Chinese graduate student at Stanford in the 1970s. Although she ranked at the top of her Taiwanese high school, her parents had no intention of sending her abroad — until her three brothers flamed out. Now, on weekly long-distance phone calls, her miserable mother and philandering father hound her to start making money.

A less-dutiful daughter studying in America might just stop calling home, but “Joan was grateful, as she was a girl and thus not entitled to anything.” At first, she brings that same sense of compliance into her marriage with a handsome Chinese architecture student. …

Watching others grasp the depth of Joan’s resolve is one of the many pleasures of “The Satisfaction Café,” which follows this determined woman decades into the future.

Not long after stabbing and divorcing her husband, Joan marries Bill, a wealthy White man twice her age, which is both a blessing and a challenge. Their unlikely relationship works surprisingly well even while inspiring some of the novel’s finest comedy. …

How does a 25-year-old former grad student adjust to managing a large house of her own? As with everything Joan does, she makes a concerted effort to get along with Bill’s siblings and adult children, but they see nothing but that gulf between him and his young Chinese wife. Regarding her as a threat to the family’s financial security and its genetic purity, they whisper racist jokes and cast her as a gold digger. Bill’s friends don’t hesitate to remind her how much they liked his previous wife.

The presumptuousness of rich people “convinced they were uniquely important” continually flummoxes Joan — and clearly amuses Wang, who also lives in the Bay Area. She has a perfect ear for the whiplash offenses and confidences of this gilded set. After treating her coldly, Bill’s sister suddenly “spoke to Joan as if they’d experienced something significant together, like high school or a stressful cruise.”

Wang mines these tense relationships for the novel’s sharpest critique of wealthy people who have faith “that things will always be such a way.” This sort of upper-crust satire could feel stale if not for the fresh way Joan reacts to their micro- and macro-aggressions: She has a scientist’s curiosity about these spoiled folks. “She was interested in snobs,” Wang writes. How do they inhabit the world? What do they eat? Where do they travel to? She finds it incredible that “luck could be distributed not only so randomly but also exponentially.” The privileged life that Bill’s family members consider an expression of their wisdom, hard work and value, Joan knows is just as accidental as her own position.

With increasing concern, she wonders if there could be a way to create more happiness in life. …

Aside from Joan’s opening assault on her first husband — carried out with a caliper! — the plot of “The Satisfaction Café” is relatively muted as it leaps through the decades of Joan’s life. In any case, the real attraction of this novel isn’t its plot but its voice. Ironic but rarely biting, Wang’s narration moves nimbly just above Joan’s perplexed perspective while catching the notes of absurdity and hypocrisy around her. That’s perfect because Joan is always within and without — participating in the culture of wealthy White people but also subjected to it, living in luxury but caught in an undercurrent of condescending comments, glances and expectations.

I wonder if in one of the dramatic highlights of this novel, a white person … touches her hair!

So, who is this Chinese woman who marries into a famously rich and cutting white family based upon? I would guess: a certain Chinese adventuress much less boring than the heroine of the novel, namely …

Paywall here.

The Satisfaction Café sounds like an intentionally tedious roman a clef about the gold-digging adventuress Wendi Deng Murdoch, the Chinese volleyball player who stole her first white American husband from his wife, but then dumped him to become Rupert Murdoch’s third wife, and who has since been linked in the press with Tony Blair and even Vladimir Putin.

Ms. Deng Murdoch would make a potentially fascinating heroine if you let her be the villainess of her fabulous story. But this book sounds dull because it appears to restrict itself largely to the acceptable target of satirizing white people rather than a nonwhite woman.

From Wikipedia

Wendi Deng was born in Jinan, Shandong, and raised in Xuzhou, Jiangsu. Her birth name was Wen'ge Deng, (邓文革), meaning "Cultural Revolution". She has two older sisters, and a brother, and both of her parents were engineers. When she was a teen she changed her given name to "Wendi". … She became a competitive volleyball player. …

In 1988, she left medical school and went to the United States on a study permit. She enrolled at California State University, Northridge, where she studied economics and was among the top scoring students. She obtained a BA in Economics from California State University at Northridge and an MBA from Yale University.

Jake and Joyce Cherry hosted Deng in their home during her studies in the United States. Later, Jake Cherry left his wife, and married Deng in 1990. While married to Cherry, Wendi obtained a green card. They divorced after 2 years and 7 months of marriage. Jake later said that they stayed together for only four to five months when he learned that Deng was spending time with David Wolf, a man closer to her age.

In 1997, she met media mogul Rupert Murdoch, who is 37 years her senior, while working as an executive at the Murdoch-owned Star TV in Hong Kong. They married in 1999 on board his yacht Morning Glory, less than three weeks after the finalization of his divorce from his second wife, Anna Murdoch (née Torv). The couple had two daughters: Grace (born 2001) and Chloe (born 2003). Tony Blair is Grace Murdoch's godfather. In June 2013, Rupert Murdoch filed for divorce from Deng, citing irreconcilable differences.

In February 2014, The Daily Telegraph and Vanity Fair alleged that Deng might have had an affair with former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair.

An article in The Economist claimed that as a result of Rupert Murdoch's suspicion that Blair had an affair with his wife, he ended his long-standing association with Blair in 2014.

In early 2018, The Wall Street Journal published a story suggesting that Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump, longtime friends of Deng, were warned by US intelligence agencies that she may be using her relationship with them to further the goals of the Chinese government. Michael Wolff, author of Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House, posited that the article was an attempt by Rupert Murdoch, owner of The Wall Street Journal, to spread the idea that "Wendi is a Chinese spy" in the aftermath of their acrimonious divorce.

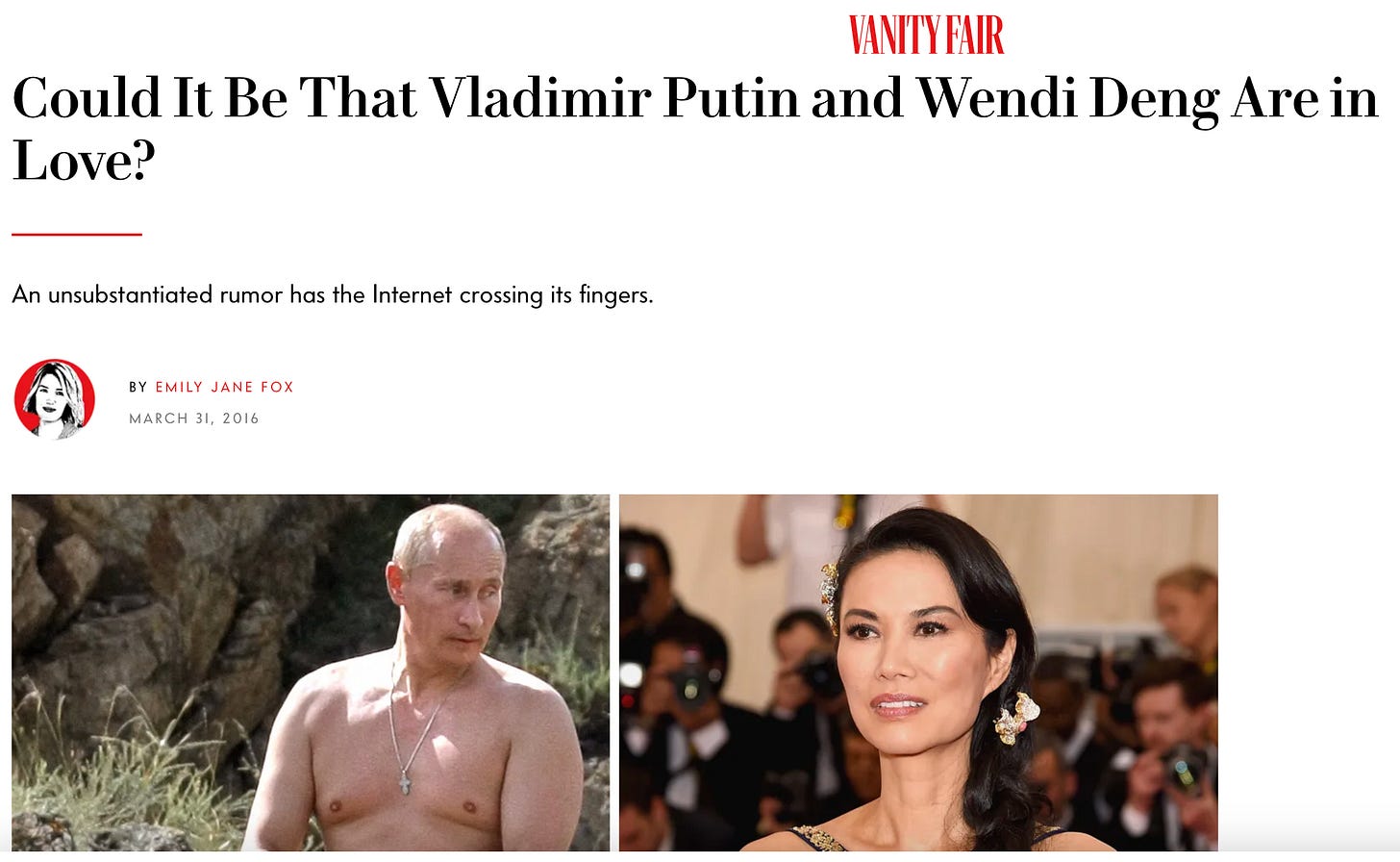

The Putin rumor seems more like wishful thinking on the part of gossip fans for a fitting can-you-top-this climax to Wendi’s odyssey. Vanity Fair snarked in 2016:

Could It Be That Vladimir Putin and Wendi Deng Are in Love?

An unsubstantiated rumor has the Internet crossing its fingers.

By Emily Jane Fox

March 31, 2016

When Rupert Murdoch filed for divorce from his then wife Wendi Deng in 2013 after 14 years and two daughters together, everyone wondered what this would mean for the 40-something mother of two who moved to America for a man 38 years her senior. Where does a woman go to find love after devoting more than a decade to a billionaire News Corp. chief, who professed his love so sweetly aboard his yacht on their wedding day before sailing off into the sunset? He was a man, after all, who plucked her out of her internship at a News Corp.-owned television station in Hong Kong, who moved downtown from his preferred Upper East Side to please her, who even suffered through grueling six A.M. sessions at the gym and downed soy-protein concoctions at her behest. Finding that kind of love—that kind of life—is a lightning strike. Rarely does it strike twice.

In 2014, Vanity Fair reproduced a purported hand-written note by Wendi to herself regarding Google CEO Eric Schmidt:

"Lisa [Schmidt’s girlfriend] will never have my style, grace … I achieved my purpose of Eric saw me looking so gorgeous and so fantastic and so young, so cool, so chic, so stylish, so funny and he cannot have me. I'm not ever feel sad about losing Eric … Plus he is really ugly … I'm soooo happy I'm not with him."

There are countless amusing stories like this about Deng Murdoch in the gossip columns. But novels and TV shows, have been strikingly hesitant to do anything juicy about the notorious man-eater.

For instance, in the Emmy-winning TV series Succession, a fictionalized version of the battle for control of the Murdoch media dynasty, Wendi Deng Murdoch gets transformed into the vaguely Middle Eastern Marcia Roy. This sets up some dramatic tension: Is she white and thus Bad, or not white and thus Good?

The character in Succession sounds, in the modern manner, much less entertaining than the original:

From the Succession Fandom site:

Marcia Roy is the third and final wife of Logan Roy. She is portrayed by Hiam Abbass.

Marcia Roy is a woman of sophistication and intelligence, is a deeply loyal partner to Logan, and loves him despite his myriad flaws. She is not afraid to be aggressive towards those who challenge Logan, including his children. Despite her efforts, Logan still betrays her repeatedly by having affairs with other businesswomen, but Marcia is willing to use these incidents to her advantage.

Little is revealed of Marcia's history throughout the series. Shiv has a background check done on her in "Lifeboats", which revealed: Marcia first appeared in Paris at 31 years old, working as a publishing assistant. She married a Lebanese businessman and has two children. She threw many parties with her husband, attended by artists and politicians, as well as a lot of "shitbags and slimeballs." However, nothing shows of her history before Paris. Shiv infers that it must have been intentionally erased.

The last paragraph seems promising, but the series is now over, and apparently nothing much was done with her character.

If you go by the account of her ex-husband, Bill Stevenson, Jill Biden was a bit of an adventuress.

> males lose interest in reading stories about other guys, when they could be the hero of their own shoot-em-up video games.

I don't think this is the reason. Warhammer slop novels still sell. I had video games growing up but would take a break to read about slaying dragons, with occasional dips into Hemingway or Cormac McCarthy

They just don't give guys publishing contracts and promote the books. The bookish man still exists, he just reads classics instead of modern novels.