The Hyperborea of the Last Woolly Mammoths

What caused so many species of Ice Age megafauna, such as the woolly mammoth, to go extinct? Occam’s razor would suggest that the arrival of humans, especially of tough Siberian hunters, was often the decisive factor in spectacular extinctions in the Old World and especially in the New.

The scientific establishment, however, tends to consider that explanation unsubtle and distasteful — after all, Siberian hunters weren’t white, so they don’t fit conveniently into anti-colonialist narratives of white guilt — so more nuance is preferred when possible. The Science thus tends to be sympathetic toward less on-the-nose theories, such as climate change or in-breeding (although the evidence is so strong for the Hunters Ate Them hypothesis that it’s hard to rule it out in all cases).

From the New York Times science section:

The Last Stand of the Woolly Mammoths

The species survived on an island north of Siberia for thousands of years, scientists reported, but were most likely plagued by genetic abnormalities.

By Carl Zimmer

June 27, 2024

For millions of years, mammoths lumbered across Europe, Asia and North America. Starting roughly 15,000 years ago, the giant animals began to vanish from their vast range until they survived on only a few islands.

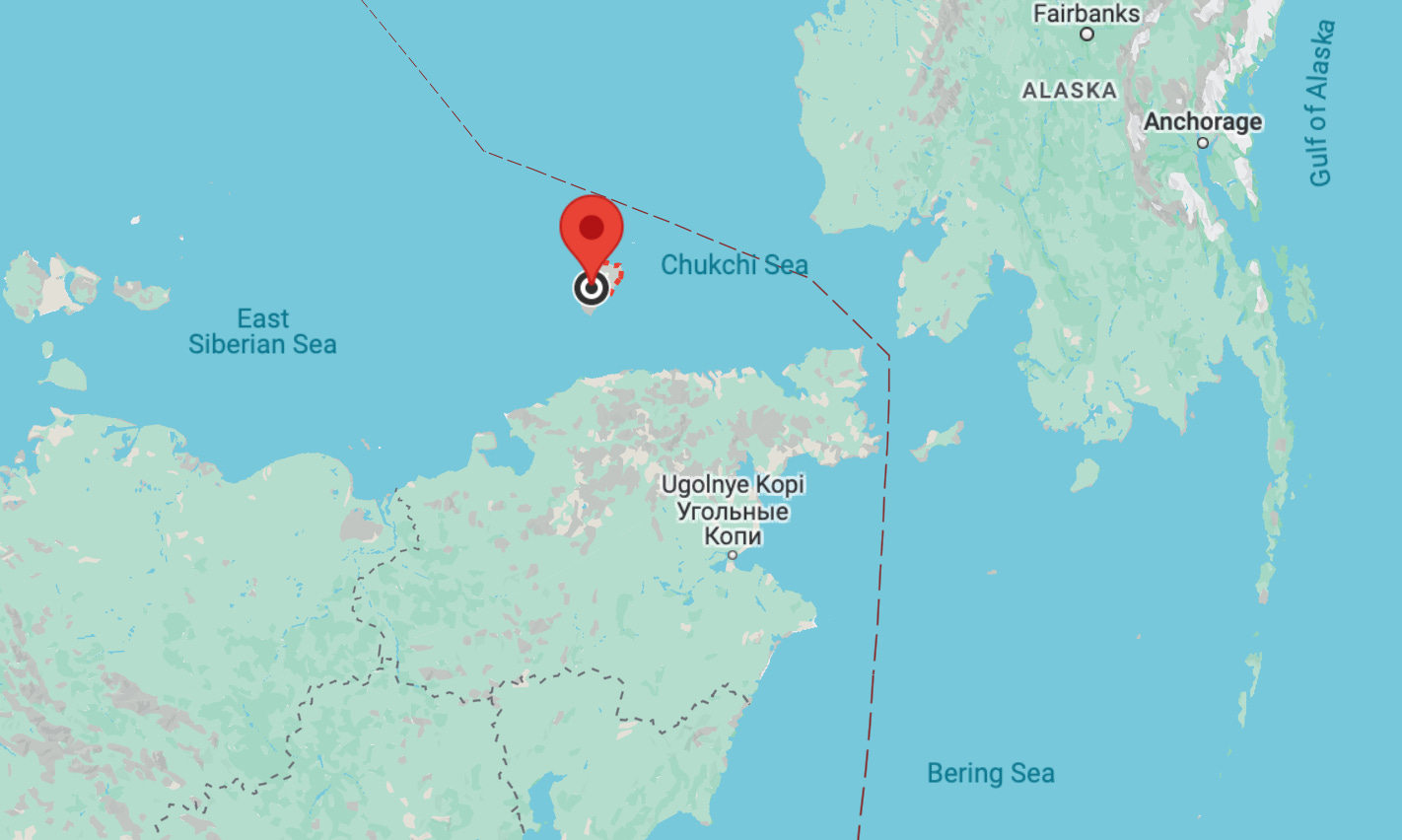

Eventually they disappeared from those refuges, too, with one exception: Wrangel Island, a land mass the size of Delaware over 80 miles north of the coast of Siberia. …

When the Wrangel Island mammoths disappeared 4,000 years ago, mammoths became extinct for good.

For two decades, Love Dalén, a geneticist at Stockholm University, and his colleagues have been extracting bits of DNA from fossils on Wrangel Island. In recent years, they have gathered entire mammoth genomes. …

The scientists concluded that the island’s population was founded about 10,000 years ago by a tiny herd made up of fewer than 10 animals. The colony survived for 6,000 years, but the mammoths suffered from a host of genetic disorders.

Oliver Ryder, the director of conservation genetics at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, said that the study held important lessons for trying to save species from extinction today. It shows that inbreeding could cause long-term harm. …

Dr. Dalén and his colleagues examined the genomes of 14 mammoths that lived on Wrangel Island from 9,210 years to 4,333 years ago. The researchers compared the DNA from the Wrangel Island mammoths with seven genomes from mammoths that lived on the Siberian mainland up to 12,158 years ago….

Dr. Dalen and his colleagues concluded that the island was founded by a remarkably tiny population of mammoths.

Before about 10,000 years ago, Wrangel Island was a mountainous region on the mainland of Siberia. Few mammoths spent time there, preferring lower regions where more abundant plants grew.

But at the end of the ice age, melting glaciers submerged the northern margin of Siberia. “There was one small herd of mammoths that happened to be on Wrangel Island when it was cut off from the mainland,” Dr. Dalén said….

But the few mammoths stranded on Wrangel Island enjoyed a tremendous stroke of good luck. The island was free of people and other predators, and they faced no competition from other grazing mammals. What’s more, the climate on Wrangel Island turned it into an ecological time capsule, where the mammoths could still enjoy a diversity of ice age plants.

The notion that mammoths, with their apparently delicate digestions, could only enjoy ice age fodder rather than the more abundant fodder of the milder millennia since the glaciers receded is a curious one.

“Wrangel Island was a golden place to live,” Dr. Dalén said.

“Golden” apparently being defined as a place too horrible for human hunters to get to.

He and his colleagues found that the population on Wrangel Island expanded from fewer than 10 mammoths to about 200. That was probably the maximum number of mammoths the island’s plant life could support.

But life was far from perfect for the Wrangel mammoths. The few animals that founded the island had very little genetic diversity, and Dr. Dalén and his colleagues found that the level stayed low for the next 6,000 years.

“They carried with them the inbreeding that they got in the early days,” he said.

Elephants have generations lengths of 20 or 25 years. Assuming mammoths were the same, that would suggest around 270 generations of mammoths grew up on Wrangel Island. Wouldn’t that be long enough to purge from the bloodline most of the more deleterious inbred genes?

As a result, the mammoths probably suffered a high level of inherited diseases. Dr. Dalén suspects that these sick mammoths managed to survive for hundreds of generations because they had no predators or competitors.

Would 71 degrees north in the Arctic Ocean really be such a utopia that genetic cripples could thrive there? Note that mammoths seldom visited Wrangel back when they could walk to it.

… The new study doesn’t reveal how exactly the Wrangel mammoths met their end. There’s no evidence that humans are to blame; the earliest known visitors to Wrangel Island appear to have set up a summer hunting camp 400 years after the mammoths became extinct.

Alternatively, we’ve so far found evidence of humans being on Wrangell as far back as 90% of the time since they went extinct. Where’s the evidence that humans didn’t get there, say, 101% of that duration ago, but we just haven’t found their campsite remains yet? Is there a lot of construction and excavation going on on Wrangel Island that would inevitably surface all evidence of human visits?

… It’s possible that a tundra fire killed off the Wrangel mammoths, or that the eruption of an Arctic volcano may have done them in.

Sounds like an easy place to die.

Dr. Dalén can even imagine that a migratory bird brought an influenza virus to Wrangel Island, which then jumped to the mammoths and wiped them out.

Or maybe the Siberian hunters who had previously wiped out most of their kin in the Old World and in the New showed up and ate them?

… Cloning might provide another way to help species recovery. Dr. Ryder and his colleagues have been freezing cells from endangered animals to preserve some of their genetic diversity. In 2021, researchers succeeded in producing a clone of a black-footed ferret from a population that had become extinct in the 1980s.

Without these interventions, an endangered species may struggle to escape a legacy of inbreeding, even after hundreds of generations. “It may still have these time bombs in its genome that don’t bode well for the long term,” Dr. Ryder said.

And cloning is going to solve the inbreeding problem how?

In contrast, here’s an article I wrote for UPI in 2001 that had since disappeared from the Internet:

Highly inbred cattle prove healthy

By STEVE SAILER

UPI National CorrespondentLOS ANGELES, Calif. Jan. 17, 2001 (UPI) -- Although inbreeding is notoriously bad for the health of offspring, a new study in this Thursday's issue of the prestigious British science journal "Nature" suggests that inbreeding can create perfectly healthy new breeds -- in the long run.

A team of British scientists lead by P.M. Visscher of the U. of Edinburgh examined the DNA of the celebrated Chillingham Cattle. Since the year 1240, these fierce white beasts have lived wild within the walls of a forested game preserve at Chillingham Castle in northern England.

Their DNA analysis confirmed that no outside cattle have mated with any of the herd in 300 years. An estimated 67 generations of inbreeding has left the small herd "almost genetically uniform."

Yet, these magnificent brutes remain fecund and healthy.

Because the feral cattle refuse to touch commercial cattle feed, twenty starved to death during the severe winter of 1947. That reduced the herd to only 13 animals. Yet, the population bounced back quickly, and now stands at 49.

And the Chillingham Cattle are notoriously virile. The famous slam-bang battles among males to become the "King Bull" who sires all the herd's calves have frequently been filmed for nature documentaries (although generally from a safe distance). These struggles for dominance were even studied back in the 19th century by the author of the modern theory of evolution, Charles Darwin.

The paper's authors suggest that over the years, Darwinian natural selection has purged from the herd's DNA the dangerous recessive genes that normally make inbreeding risky. Chillingham calves unlucky enough to inherit two copies of a lethal recessive gene generally died before they could pass on their genes. Over time, this merciless process removed the bad genes from the herd.

In contrast, in a herd with frequent out-breeding, individuals would not be very likely to inherit two bad recessive genes. Yet, because the dangers of dying from two bad recessives are lower in a more genetically diverse population, these bad genes would linger longer.

… [He] pointed out that when animal keepers create a new breed of domestic animal, they use inbreeding to reinforce a desired trait. Breeders expect the new inbred strain will suffer major genetic health problems during the first several generations. Yet, according to a common rule of thumb, by the seventh generation the survivors should be as vital and fertile as the original population.

This does not mean that new inbred strains are permanently immune to genetic problems caused by incest or isolation. As the population expands, mutations introduce new dangerous recessive genes. This makes dangerous once again the incest and genetic isolation common at the most unscrupulous puppy mills.

Just as breeders use isolation and inbreeding create new breeds in the barn and kennel, the same processes lead -- albeit more slowly -- to the evolution of new races and species in the wild. Paradoxically, the spectacular genetic biodiversity of the natural world exists because of a lack of genetic diversity within breeds and species. Without physical segregation leading to barriers to random mating, animals would never proliferate into so many fascinating regional variations.

This study also has relevance for preserving endangered species. Government wildlife scientists are concerned that small populations may not be salvageable due to a lack of genetic diversity. Darwinian logic, however, suggests that only wild breeds that have shrunk rapidly in recent generations may be in grave danger of an even more catastrophic collapse due to the accumulation of dangerous recessive genes. In contrast, small populations that have stabilized their numbers in the manner of the Chillingham Cattle may have already passed through the worst danger zone caused by inbreeding.

jared diamond may be crankey, but his thesis on the domesticability of species seems somewhat sound.

This reminds me how the scientific "discourse" also twists itself in knots to avoid the Occam's razor explanation that syphilis was brought from the New World to the Old by Columbus's returning men, because to admit that would somehow diminish the suffering of Native Americans to Old World diseases they had no natural immunity to.