Was Oliver Sacks a Scientist or a Self-Help Guru?

A New Yorker article documents how much of "Awakenings" and "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat" were made up.

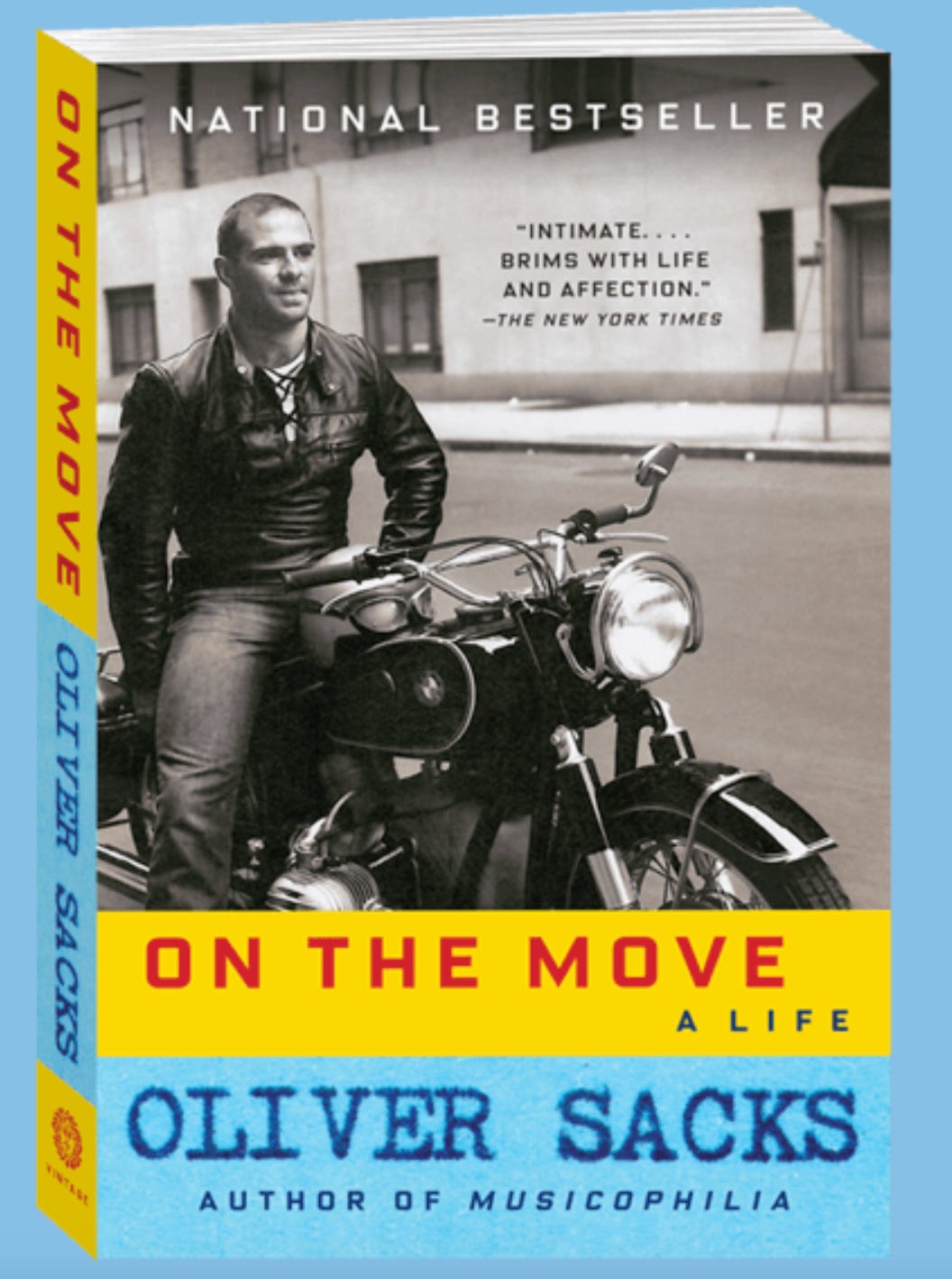

Oliver Sacks (1933-2015), a literary prodigy turned neurologist turned literary prodigy who wrote best-selling case studies of various brain syndromes, was a big deal in the 1970s-1980s.

For example, his 1973 book Awakenings about how he’d given a new drug to dozens of encephalitis patients who’d been close to comatose for decades with initially miraculous results, was made into a movie with Robin Williams as the Sacks character and Robert De Niro as his most spectacularly responsive patient:

Personally, I’d have preferred the more obvious casting: De Niro as the mensch doctor and Williams as the twitchy patient. Sacks was a massive, energetic bear who’d set some sort of weightlifting record in his youth and went swimming in the East River every day late in life. De Niro could impersonate that physicality better than Williams.

But the more I had read dazzling, mind-blowing case studies by Sacks, the less he appeared scientifically trustworthy.

Over time, though, after the 1980s, his books got progressively more realistic, but also duller. So I stopped reading them even though I believed them more.

Now in The New Yorker, a writer given access to Sacks’ journals documents - although it shouldn’t have come as a surprise — that he made a lot of stuff up.

Oliver Sacks Put Himself Into His Case Studies. What Was the Cost?

The scientist was famous for linking healing with storytelling. Sometimes that meant reshaping patients’ reality.

By Rachel Aviv

December 8, 2025

… again and again, his psychic conflicts were displaced onto the lives of his patients. He gave them “some of my own powers, and some of my phantasies too,” he wrote in his journal. “I write out symbolic versions of myself.”

Aviv blames Sacks’s various self-obsessions on the homophobia of 1970s Greenwich Village:

… Sacks, who was closeted until he was eighty …

Well, no, he’d been a black leather Santa Monica Muscle Beach weightlifter and motorcyclist. After moving to New York, he was part of poet W. H. Auden’s coterie. I recall writing a term paper about Auden in high school fifty years ago and his homosexuality had been well-known for decades by then. Evelyn Waugh’s 1942 novel Put Out More Flags parodies Auden and Isherwood as the gay poets Parsnip and Pimpernell who flee to New York the moment bombs start falling on London.

Sacks’ macho, misogynistic varietal of gayness, like Charles Kinbote’s in Nabokov’s Pale Fire, was hilariously obvious to close readers of his book about his tendency toward psychosomatic illnesses, A Leg to Stand On.

At some point in mid-life, however, Sacks decided to be celibate for yet another of the various eccentric reasons he came up with for doing whatever he felt like doing at the time.

Were his most famous books honest?

But, in his journal, Sacks wrote that “a sense of hideous criminality remains (psychologically) attached” to his work: he had given his patients “powers (starting with powers of speech) which they do not have.” Some details, he recognized, were “pure fabrications.” … Sacks had “misstepped in this regard, many many times, in ‘Awakenings,’ ” he wrote in another journal entry, describing it as a “source of severe, long-lasting, self-recrimination.” …

But as Aviv points out, Sacks’ patients didn’t complain all that much that he tended to add 50 points to their IQs in his books. They appreciated that this brilliant, kind, endlessly energetic man had been concerned about them. If he wanted to depict them as versions of one or another aspect of himself, well, they were flattered.

… Sacks spoke of “animating” his patients, as if lending them some of his narrative energy. After living in the forgotten wards of hospitals, in a kind of narrative void, perhaps his patients felt that some inaccuracies were part of the exchange. Or maybe they thought, That’s just what writers do. Sacks established empathy as a quality every good doctor should possess, enshrining the ideal through his stories. But his case studies, and the genre they helped inspire, were never clear about what they exposed: the ease with which empathy can slide into something too creative, or invasive, or possessive. Therapists—and writers—inevitably see their subjects through the lens of their own lives, in ways that can be both generative and misleading.

An important question is whether some people, such as titanic Oliver Sacks, are more interesting than other people, such as his defective patients?

On the other hand …

After “Awakenings,” Sacks intended his next book to be about his work with young people [boys, I presume] in a psychiatric ward at Bronx State Hospital who had been institutionalized since they were children. The environment reminded Sacks of a boarding school where he had been sent, between the ages of six and nine, during the Second World War. He was one of four hundred thousand children evacuated from London without their parents, and he felt abandoned. He was beaten by the headmaster and bullied by the other boys. The ward at Bronx State “exerted a sort of spell on me,” Sacks wrote in his journal, in 1974. “I lost my footing of proper sympathy and got sucked, so to speak, into an improper ‘perilous condition’ of identification to the patients.”

He was especially invested in two young men on the ward whom he thought he was curing. “The miracle-of-recovery started to occur in and through their relation to me (our relation and feelings to each other, of course),” he wrote in his journal. “We had to meet in a passionate subjectivity, a sort of collaboration or communication which transcended the Socratic relation of teacher-and-pupil.”

Uh …

Paywall here.