Where Are Baseball Players Born?

How do Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Japan, and U.S. differ at developing MLB baseball players?

Baseball is not a truly global team sport like soccer or basketball, but it still ranks up there with, say, cricket. It’s mainly played in three parts of the world: North America (U.S. and Canada), the northern half of Latin America down through Venezuela and Colombia, and northeast Asia (Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan).

Apparently, American baseball spread outward around the Caribbean from Cuba, the culturally dominant Spanish colony. Baseball is tied into Cuban nationalism (e.g., it’s widely believed that Fidel Castro almost made the major leagues as a pitcher, although in truth he was a better high school basketball player), so there are multiple narratives.

One, popular in the U.S., is that baseball became hugely popular after it was introduced by American soldiers who defeated Cuba’s Spanish colonial overlords in 1898. Another, popular in Cuba, is that it was already a massively popular game because it had been adopted by the Cuban independence movement from the 1860s onward as a rebuke to the bullfighting of Cuba’s colonial master, Spain.

I’m sympathetic to the latter story, but the details seems a little off because most early Cuban cultural contacts with the U.S. were through the Gulf Coast, where baseball was not terribly popular until the late 19th Century. For example, the first great baseball player from the Deep South was Ty Cobb, the Georgia Peach, who reached the major leagues in 1905.

Before the Civil War, baseball had been a northern sport, played with various rules in New York, Massachusetts, and other northern locales. During the Civil War, Union soldiers had a lot of time on their hands to play each other on the baseball diamond (or baseball square in the Massachusetts Game), but they needed to agree on the rules. Eventually, the New York Game, the best organized of the variants, won the loyalty of Northern soldiers and became the National Pastime when the North won the war.

But that meant baseball was not very popular in the South for a generation or so after the war.

Also, was bullfighting ever really truly supposed to be a sport for the Cuban masses? Bullfighting is amazing, but it’s more of an art form than a sport. Thus, bullfighting correspondents are less like sportswriters than art critics. As a sport for the masses, it sounds kind of like grand opera would be.

“Well, Little Jose, you have today off from school. What are you going to do?”

“Me, Pedro, Juan, Diego, and the rest of the kids are going to get together and put on The Barber of Seville!”

“Have fun!”

So, I dunno what the precise story is with the origins of Latin American baseball.

But Cuba’s role is undeniably important in the spread of Latin baseball.

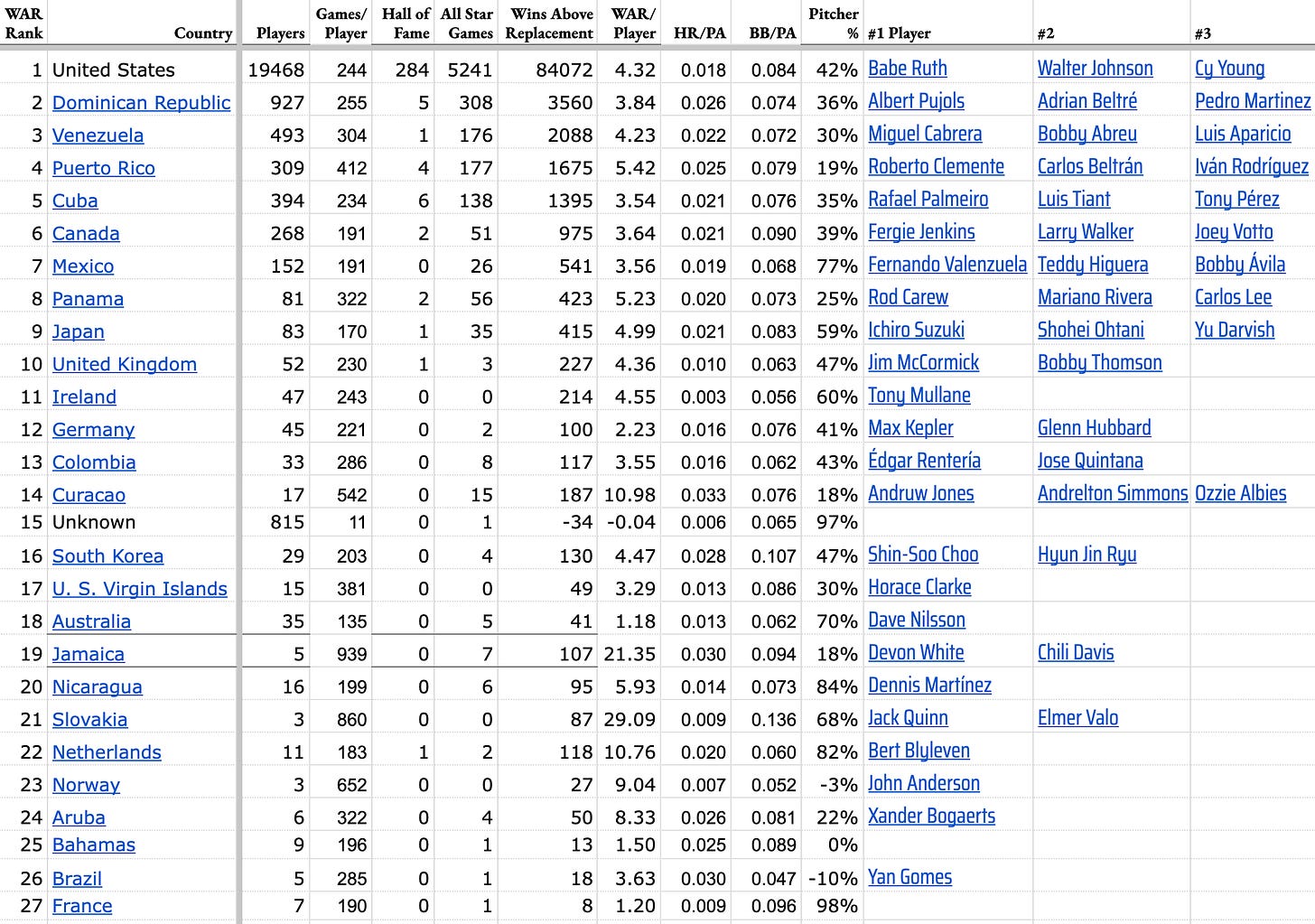

Baseball Reference tabulates major league players by country of birth. So I’ve ranked country of birth in order by today’s usual all-around metric of Wins Above Replacement *

Paywall Here. After it, I’ll explain what I see from this table.

Not surprisingly, the United States is the native country of big leaguers who account for about 85% of WAR going back to the final third of the 19th Century.

In 2025, 73% of opening day rosters were American-born, followed by 10.5% Dominicans. Baseball teams carry more relief pitchers lately, who tend to be more white American than other positions, so the long term trend toward more foreign-born players hasn’t been all that steep lately. Still, Dominicans per capital are about four times as likely per person as Americans to make the majors. In contrast, Mexicans are only about 1/24th as likely to to make MLB rosters as Americans and about 1/100th as likely as Dominicans.

Second in terms of all time WAR is the Dominican Republic, followed by Venezuela, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Canada, Mexico, Panama, and Japan.

Per capita, Puerto Rican big leaguers tend to be even better than Dominicans (as measured in WAR per player, not per person in the overall population). This seems to be because Puerto Rican prospects are treated as Americans contractually, and must come through the amateur draft, so they are more expensive on average than Dominicans and thus more carefully selected. In contrast, big league teams are allowed to sign hordes of cheap 16 year old Dominicans and enroll them in “baseball academies” the teams have constructed in the DR. So, there are more marginal Dominicans in the big leagues than Puerto Ricans.

Cuba and Japan would rank higher if their authorities (the government in Cuba, the baseball leagues in Japan) hadn’t made it hard for their stars to leave. A number of Cuban big leaguers got here on rafts, while there was only one Japanese player let play in the U.S. before 1995. Similarly, the American leagues and Mexican leagues have squabbled at various times, and since 2018 it’s been harder for Mexican stars to sign with MLB teams.

Northeast Asians have been getting taller and baseball favors height.

American baseball had its notorious color line until 1947, which slowed recruiting from the Caribbean, but seven Dominicans played in the the MLB before WWII. A tiny number of Cuban players before WWII would probably have been ruled out for being kind of black if they’d been born in America. Cuban Dolph Luque, who pitched from 1914-1935 and went 27-8 and 1.93 in 1923 for the Reds, is usually considered the first Latin American-born star.

The difference between Dominicans and Mexicans is striking. The all time best Mexican-born big leaguer is Dodger pitcher Fernando Valenzuela, but 18 Dominicans have higher career WAR totals than Fernando.

Why? One reason is that big league Dominicans tend to be quite black (probably blacker than Dominicans on average), while Mexicans tend to be mestizos. The Dodger scout who discovered Fernando said the reason he didn’t find more Fernandos in Mexico was that Mexicans tend to be too short-legged to become baseball stars.

The greatest Mexican-American player was slugger Ted Williams, whose mother was slightly mestizo-looking. But Ted was 6’3”. Since Ted, many American-born Mexican-American stars like Evan Longoria have been half-white.

In contrast, the greatest American-born Dominican, Alex Rodriguez, was more mulatto than black.

This Nature reason in turn leads to Nurture differences: baseball is now wildly popular in the DR.

Countries differ in how many of their stars are pitchers of position players. Down through history, 42% of the WAR earned by Americans has been earned by pitchers rather than position players. The Dominican Republic is fairly similar at 36% (e.g., crafty hurlers like Juan Marichal and Pedro Martinez).

In contrast, while African Americans used to be outstanding pitchers (Satchel Paige, Don Newcombe, Bob Gibson) and catchers (Josh Gibson and Ray Campanella), in recent decades as the NFL and NBA have won the hearts of African-Americans, the few American black ballplayers tend to get funneled toward centerfield or shortstop (for fast blacks) or first base (for slow, strong blacks) because integrated baseball youth teams have lots of whites to pitch, catch, or play third. In contrast, the unintegrated DR produces more well-rounded squads, so it has lots of fine pitchers and catchers.

Puerto Rico is only 19% pitcher WAR, while Mexico is 77% pitcher WAR (largely Fernando Valenzuela and Teddy Higuera Valenzuela, both portly 1980s lefty screwballers, although the latest reports is that they weren’t close kin). Japan is also pitching-centric. E.g., the rich Los Angeles Dodgers have recently signed pitchers Roki Sasaki and Yoshinobu Yamamoto and unique slugger/pitcher Shohei Ohtani who is scheduled to pitch an inning today as part of his pitching comeback from injury.

Australia is 70% pitcher WAR without having yet developed a really fine pitcher.

Baseball and cricket are largely culturally antagonistic. If your country plays one, it doesn’t play the other. Only five Jamaicans have made the major leagues, but they tended to be pretty good. Australia has been producing some tall relief pitchers lately.

Dutch-colonized Curacao and Aruba have been producing some stars over the last generation.

Free-swinging Latin American batters used to draw fewer walks than Americans, but the gap seems to have closed in this century. The Caribbean motto was, “You can’t walk off the island” — i.e., American scouts wanted to see you hit the ball hard.

But Caribbean players have become much more powerful in recent decades, thus scaring pitchers into not throwing the ball down the middle of the plate. Is this because of better nutrition or because you can legally buy steroids without a prescription at Dominican drug stores?

European-born big leaguers tend to be either old-timers who immigrated with their families when young or U.S. servicemen’s kids. Hall of Fame pitcher Bert Blyleven was a rare post-WWII immigrant from the Netherlands.

For example, most Irish-born players came during the Dead Ball era before Babe Ruth, so the Irish natives hit few home runs but stole a lot of bases. However, this reflects the tendencies of baseball more than a century ago rather than the Irish being innately fast and small.

Max Kepler of the Twins is a rare major leaguer who learned to play baseball playing in German-language leagues. His American-born mother and Polish-born father are professional ballet dancers who made their careers in Berlin.

Baseball tends to be a warm weather sport because it needs dry infield dirt. For example, Toronto fans support a major league team, the Blue Jays. But not that many Canadian natives get to the big leagues.

815 players are listed as of “Unknown” nativity, but virtually all are, say, a guy with a name like John Smith who had a cup of coffee in the big time in 1904. The Unknowns average -0.04 Wins Above Replacement, so they were replaced.

Ed Porray, who played in three games in 1914 for the Buffalo Buffeds of the short-lived Federal League and was credited/demerited with -0.4 WAR, is the only major leaguer listed as having been born “At Sea.”

You can’t say baseball isn’t fanatical about its statistics.

* Note: What is WAR? A typical regular is worth about two additional wins per season for his team over a generic replacement player that can be picked up from Triple A minors or off the waiver wire, while a superstar is worth six or eight incremental wins per season, with a Judge or Ohtani approaching ten WAR).

Makes me think of the (probably held here before) discussion of Kenyan and Ethiopian marathon runners. I remember the early debates about what made them so good: training conditions, especially at elevations; escaping poverty; inherited physical differences. The ones I had the pleasure to watch while racing (briefly, as they outpaced us) had miniscule torsos, slightly longer limbs, and no body fat. This was before modern sports medicine, measurement, and training, so hypotheses leaned heavily on the romantic/sociological "escaping poverty" theme. But it seemed to me that many successful far-northern European-origin female runners shared those traits, including having narrow hips.

But some females with wider hips and legs now do well at ultramarathoning.

I wonder if genetic testing would reveal advantages from origin countries of players lumped together as "American." Look at Dwight Gooden (an obsession of mine, but only because I met him a few times, am a generational Mets fan, and he is pretty odd-looking). Tiny torso, long arms and legs, larger than African runners likely due to nurture and genetic mixing, but by my sights, he used his body the way those first-generation African marathoners ran, with discipline but also an utter focus on limb release.

Only my non-scientific observation. But I lived for running and made good spare money in grad school taking part in several experiments related to the then-new computerized sports training sciences and some vitamin/suppliment ones, being at the school muddled in with the CDC. A genetic and national breakdown of baseball players would be interesting.

"The greatest Mexican-American player was slugger Ted Williams, whose mother was slightly mestizo-looking. "

Williams was about 75-80% European. It's a bit mech, since Ted never seriously identified as being Mexican during his lifetime. Perhaps because in his autobiography he seems to harbor some deep seated resentment vs his mother (half Mexican) whose life centered around her participation in the Salvation Army at the expense of taking care of her family (and by extension, not devoting enough time to his upbringing).

In his autobiography, Cuban born Jose Canseco devotes nearly half a chapter to players from various nations. One prominent example he uses is the DR Miguel Tejada, who started out slow with below average stats but within a few years, was putting up stats that were simply amazing. Without directly saying it, Canseco attributes Tejada's sudden rise to PEDS, and in his mind the answer is fairly simple. In the DR and other Caribbean nations, there is abject poverty for most locals, and the one way out of that hard life is thru baseball. He makes the point that if you had one chance in a million to get out of that poor nation, play in MLB where you could potentially make tons of money and thus take care of your family for life, wouldn't you take that chance, even if it meant using PEDS? In Canseco's mind, in order to guarantee a consistently amazing on field performance (and thus score big money contracts) is thru PEDS. As Carribbean nations laws and regulations at the time weren't as strict as the US regarding PEDS, it was fairly easy for local players to obtain them and thus have a better opportunity at reaching the MLB. In Canseco's view, failure wasn't an option for impoverished Caribbean locals playing ball. and thus PEDS in his view was the one guarantor of success (playing in MLB).

"What is WAR? A typical regular is worth about two additional wins per season for his team over a generic replacement player that can be picked up from Triple A minors or off the waiver wire, while a superstar is worth six or eight incremental wins per season, with a Judge or Ohtani approaching ten WAR)."

This is the one Sabermetric based stat that Steve has finally convinced me to endorse (with perhaps some cautious corrolaries, namely, don't completely ignore and neglect starting pitchers who traditionally pitched 30% or more complete games during their careers).

IF Ohtani and Judge are worth 10 WAR, then Babe Ruth would certainly have to be ca. 12-15, and we have a definitive link to demonstrate it.

In Ruth's first five years with NY, the Yankees won the AL Pennant 3 times and finished no lower than 3rd place.

In 1925 due to a still mysterious illness, Ruth was out for most of the season, and the Yankees finished in 7th place, at 69-85. A record they wouldn't finish that low again until 1965, two generations later. By pretty much every metric, Ruth had the worst statistics of his career as an everyday player. During the offseason Ruth worked out, lost weight, dieted and was ready for the following season to return to his usual superstar form.

In 1926 with Babe Ruth back in the lineup healthy, the Yankees went 91-63 and won the AL Pennant. That's a 22 W noticable difference over the previous season. The lineup was basically the same (except for a healthy Ruth. It was also Lazzeri's rookie season and Gehrigs first full season so that certainly helped, so that must be noted as well).

But the main factor remains that Ruth was healthy again and his stats were up to where they had been pre-1925 levels.

If anything, this should demonstrate that of the 22 W's NY gained with Ruth back in the lineup*, that he was directly responsible for at least 15, if not say 16-18 of those additional wins. Going from next to last place to winning the pennant mainly because one of the greatest players to have played in MLB made all the difference to NY's standings.

*(In '26, Ruth played in 152 out of NY's 154 games that season)