Why are AP tests being made easier?

Beginning in 2022, the College Board has been grade-inflating scoring of its Advanced Placement exams.

The Advanced Placement (or AP) test is probably the best college admission test that isn’t used for college admissions. If you are going to test prep in the modern mode, while you are being Tiger Mothered, you might as well learn some chemistry or European history.

Still, the AP is used for other sensible things like getting out of a final semester or a year of expensive college tuition.

So, while the AP test appears to be not broken, the College Board appears intent on breaking it.

America has endless self-created problems over the existence of racial gaps. For example, you might not be shocked to learn from the College Board’s report “Understanding Racial/Ethnic Gaps in AP® Exam Performance” that:

Like other measures, student performance on AP® Exams also reveals gaps by race and ethnicity. Average scores (on the 1-5 AP scale) across all 2022 AP Exams, for example, are lower among Black (2.1) and Hispanic students (2.4) than among White students (3.0) and Asian students (3.4).

In the U.S., high schools students take millions of Advanced Placement tests each May. These are scored from one to five with a five representing an A on an introductory course at a routine college, a 4 a B, a 3 a C, a 2 a D, and a 1 an F.

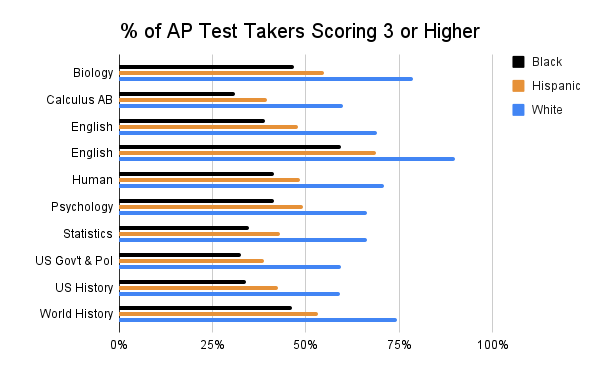

Here’s a graph I made from data in that 2023 College Board report of what percentage of each race score at least a 3 on the top 10 most AP test:

Paywall here:

It’s striking how little variation there is from one subject to the next. On all ten tests, Hispanics outscore blacks, but always by less than 50% of how much whites outscore blacks.

It would be interesting to see Asians graphed as well, but who cares about them?

Why are scores on English Lit so much higher? Because English Lit in 2022 pioneered inflating AP test scores as part of the College Boards plan to boost AP scores. That didn’t close The Gap, but it did mean that over 50% of blacks scored a passing 3 or higher in English Lit these days, unlike in any of the other top ten most popular AP tests in 2022.

What can be done to close The Gap?

Realistically, probably nothing.

It’s usually assumed that nobody has ever thought of Closing The Gap before, so All We Have To Do is, obviously, x, y, or z, or whatever panacea the latest exponent of the conventional wisdom comes up with off the top of his head, which, no doubt, he assumes, nobody has ever thought of trying before.

My recollection from the 1972-1973 high school debate season (Topic: funding public schools), however, is that Closing The Gap had been of obsessive interest to the well-funded since the mid-1960s.

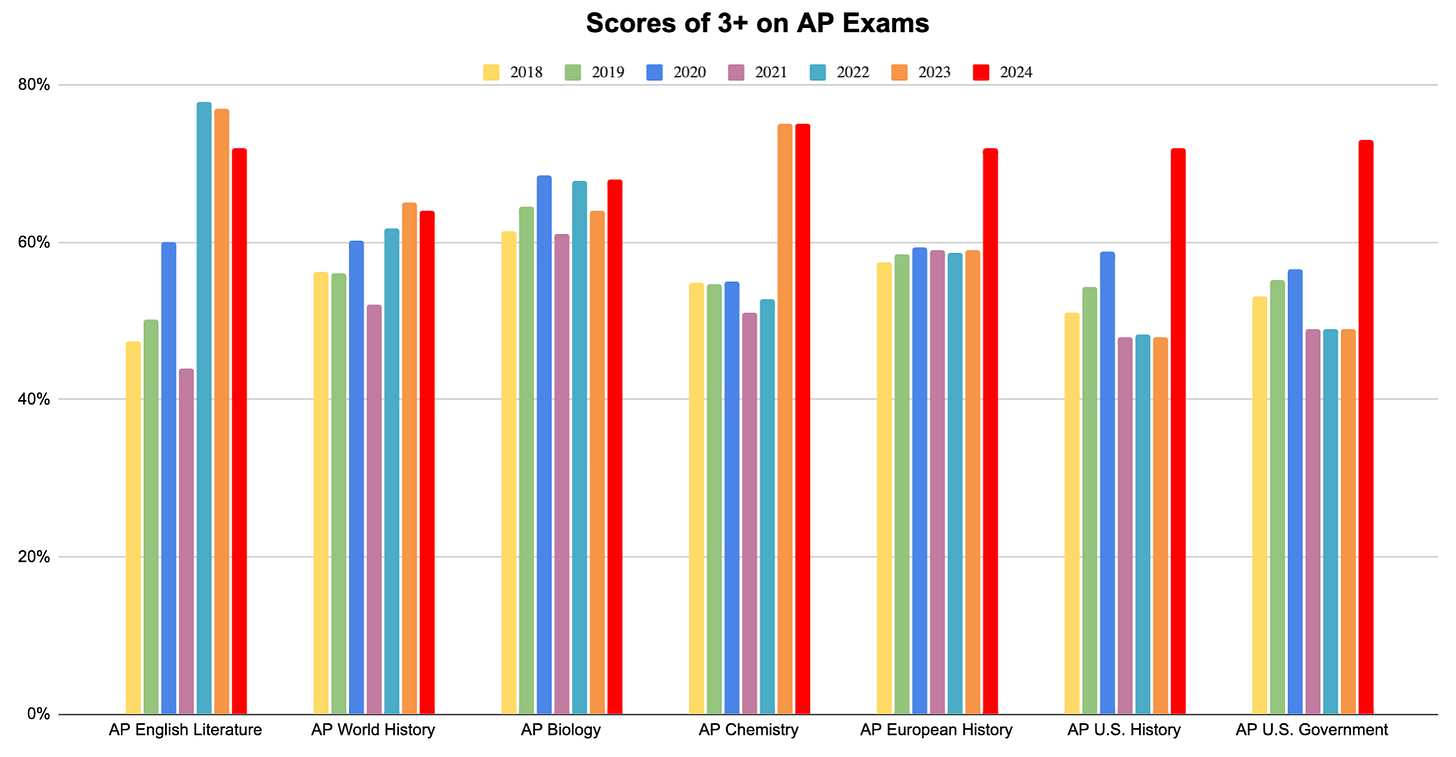

One solution, however, has always been simple: inflate scores, whether GPAs or AP test scores. Not surprisingly, the College Board has been doing just that during the Racial Reckoning, starting with the AP English Literature test in 2022, followed by the formerly brutal AP Chemistry in 2023, and AP European History, AP US History, and AP US Government in 2024.

From MarcoLearning in 2024:

The Great Recalibration of AP Exams

by John Moscatiello

The Advanced Placement program is undergoing a radical transformation. Over the last three years, the College Board has “recalibrated” nine of its most popular AP Exams so that approximately 500,000 more AP exams will earn a 3+ score this year than they would have without recalibration. If this process continues in other exams in the coming years (as we expect it will), approximately 1,000,000 more AP Exams every year will earn a 3+ score.

Why are they doing this?

Besides making it easier for blacks and Hispanics to score high enough to get college credit, the intention is to get more not-so-bright kids to sign up at $99 per test by giving them a more plausible chance of scoring high enough to get college credit. The AP tests are now competing with “dual credit” programs in which high school students can get both high school and college credit simultaneously, and without passing any national standardized tests.

After all, colleges have been severely inflating their own grades, often switching from A to B to C to A to A- to B+, so why not hand out cheap high scores on AP tests too?

Of course, the College Board has been making it harder to analyze its data. Higher Ed Data Stories opined last year:

Changes in AP Scores, 2022 to 2024

July 06, 2024

Used to be, with a little work, you could download very detailed data on AP results from the College Board website: For every state, and for every course, you could see performance by ethnicity. And, if you wanted to dig really deep, you could break out details by private and public schools, and by grade level. I used to publish the data every couple of years.

Those days are gone. The transparency The College Board touts as a value seems to have its limits, and I understand this to some extent: Racists loved to twist the data using single-factor analysis, and that's not good for a company who is trying to make business inroads with under-represented communities as they cloak their pursuit of revenue as an altruistic push toward access.

They still publish data, but as I wrote about in my last post, it's far less detailed; what's more, what is easily accessible is fairly sterile, and what's more detailed seems to be structured in a way that suggests the company doesn't want you digging down into it. …

Should they be getting credit for these results? Do the changes in performance mean that students are more qualified, or that the tests are easier? And in some subjects, does giving credit for some courses actually set students up for failure in subsequent classes?

Is it altruistic to let freshmen squeeze into college 201 classes instead of 101 classes because they got a grade-inflated 3 on their AP exam?

Really?

A large fraction of first semester college students run into massive academic and psychological problems. For example, decades ago a distant kinsman of mine aced his AP tests and hence tested out of his entire U. of Illinois freshman year classes. But the U. of I. is a tough college:

So he then flunked most of his sophomore-level first year courses because he wasn’t mature enough to be thrust into 200 level courses. Now he’s a cop, which isn’t a bad job. But still…

This is problematic because College Board has spent a lot of money lobbying state legislatures to pass laws requiring public universities grant credit for AP exams (usually a 3 or above). The assumption on college campuses is that--despite some mistrust of the College Board and their methods--they have good psychometricians who ensure test design meets rigorous standards that ensure a grade of 4, for instance, means the same thing today as it did five years ago.

But the incentive to enforce that rigor is gone, since states have effectively endorsed the outcomes of these exams as valid and worthy. College Board can now shift to growing market penetration, as they do when they encourage school districts to push AP, and encourage even students who might not be prepared to take AP classes.

It’s almost as if DEI and profit work together…

It seems that aside from the racial incentives, there is general society-wide tendency over the past 3-4 decades to try to redefine reality rather than accept concrete and perhaps disappointing truths. DIE, restorative justice, gender woo, etc. are all efforts to ignore rather obvious realities. To a large extent I chalk this up to cultural and economic decadence as a result of what was essentially an uninterrupted rise in American economic and cultural dominance over the course of 60 years or so. No child should be below average, so let's game the educational system to makes sure even more kids are high achievers on paper.

We are obviously entering a new era, one in which the US's influence on these fronts is under pressure and not what it once was, and could decline even further although we will still be a major player. I wonder if that will concentrate the national mind to some extent and contribute to casting aside some of the fantasies we can no longer afford to indulge in.

I went to Salisbury State College beginning in 1978 even before test scores were vulgarized by the egalitarians of the universities. Salisbury was a cheap place for the Eastern Shore locals and the suburbanites of Baltimore and Washington DC to go to and see whether they were college material. The Freshmen and Sophomore years weeded out the riff-raff, those who shouldn't have gone to college in the first place. I knew plenty of them. The most memorable one was a young man of Polish extraction from the Baltimore industrial suburb of Essex who left college, joined the Navy, left the Navy and became a pot farmer in California and Hells Angel. He ended up spending time in a Michigan state prison for drug smuggling.