Do Famous Novels Make Famous Films?

Gore Vidal, Shelby Foote, and other discriminating judges ranked the 100 best novels of the 1900s. How good were the movie adaptations of their Top 100 novels?

People love to argue over whether the book is better than the movie or vice-versa. I got interested instead in asking about examples of where both the book and the movie were really good (e.g., The Maltese Falcon, Gone With the Wind, Lord of the Rings, and A Clockwork Orange).

I decided to look into the question of whether a great novel makes for a great film systematically by comparing a list of acclaimed novels to the ratings of their cinematic adaptations.

For the top 100 novels of 20th Century fiction in English, I used one of the more Dead White Maleish lists, the 1998 Modern Library Top 100 Novels ranking. This was a Y2K project with the editors of Random House suggesting 400 nominee novels that were then voted on by a distinguished panel of not-dead-yet highbrows: Christopher Cerf, Gore Vidal, Daniel J. Boorstin, Shelby Foote, Vartan Gregorian, A. S. Byatt, Edmund Morris, John Richardson, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and William Styron (most of whom were published by Random House). That’s a pretty impressive set of judges.

Not surprisingly, 59 of the top 100 novels had been published by Random House. Styron made the list for Sophie’s Choice, but Byatt didn’t for Possession nor did Vidal (I’m guessing Lincoln is his best novel.)

I’m sounding cynical, but despite the corporate promotional aspect, it’s a highly respectable list.

Anyway, as I’ve often pointed out, when you do this kind of list analysis, it’s not crucial that you start with the perfect list. It’s just important that the list is not too biased on the question you are investigating. In this case, I want to know if famous novels make for famous films.

For example, a list of great novels that made great movies would be no good for my purposes because it would bias the answer, as would a list of great books that made bad movies.

In contrast, this Modern Library ranking of top novels was not chosen with their movie adaptations in mind. There might well be some subconscious bias, but if there is, it’s not obvious in which direction it is, other than perhaps in picking a great novelist’s book to recognize, they tend to recognize one that made a great movie.

In general, the Modern Library list is, if anything, biased toward famous novels that might have been filmed. For instance, the list is weighted toward the modernist classics from between the Wars, giving a lot of time for a movie to be made by now.

Not surprisingly, the judges voted James Joyce’s Ulysses as number one (with also The Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man and Finnegans Wake in the top 100). They also chose four books by Joseph Conrad, and three each by William Faulkner, Henry James, D. H. Lawrence, E. M. Forster, and Evelyn Waugh.

Only a few late 20th Century novels made the list. For instance, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest did not.

There are few children’s or young adult novels other than Jack London’s The Call of the Wild and, perhaps, Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, George Orwell’s Animal Farm, Richard Hughes’ A High Wind in Jamaica, and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. (But are those really kids’ novels?) F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, which came in second, is constantly assigned in schools, but it’s not an easy book. J. R. R. Tolkien, Roald Dahl, and Dr. Seuss didn’t make the list.

It’s also light on genre fiction, with little sci-fi other than the three classic English dystopian novels Brave New World, 1984, and A Clockwork Orange, plus Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughter-House Five.

Comic genre genius P. G. Wodehouse didn’t make the list, perhaps because it would be hard to choose among his dozen best books.

Of the big three of pre-War American noir genre fiction, Dashiell Hammett and James M. Cain had one book each, but Raymond Chandler did not.

On the other hand, the list is fairly light on experimental fiction after the stream of consciousness innovations of Joyce, Faulkner, and Virginia Woolf. E.g., Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow didn’t make it.

Only nine books by female authors and two by black authors (Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison) made the top 100. Three novels were by South Asians (two by V. S. Naipaul and one by Salman Rushdie). Standard choices of 21st Century lists such as Beloved by Tony Morrison and Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe are missing.

Overall, I’d call the list highly respectable upper middlebrow literature. So, the list ought to be pretty skewed toward being made into films by white male moviemakers with good taste and three digit IQs (i.e., most filmmakers until the Great Awokening).

And indeed 74 of the 100 have been filmed at least once.

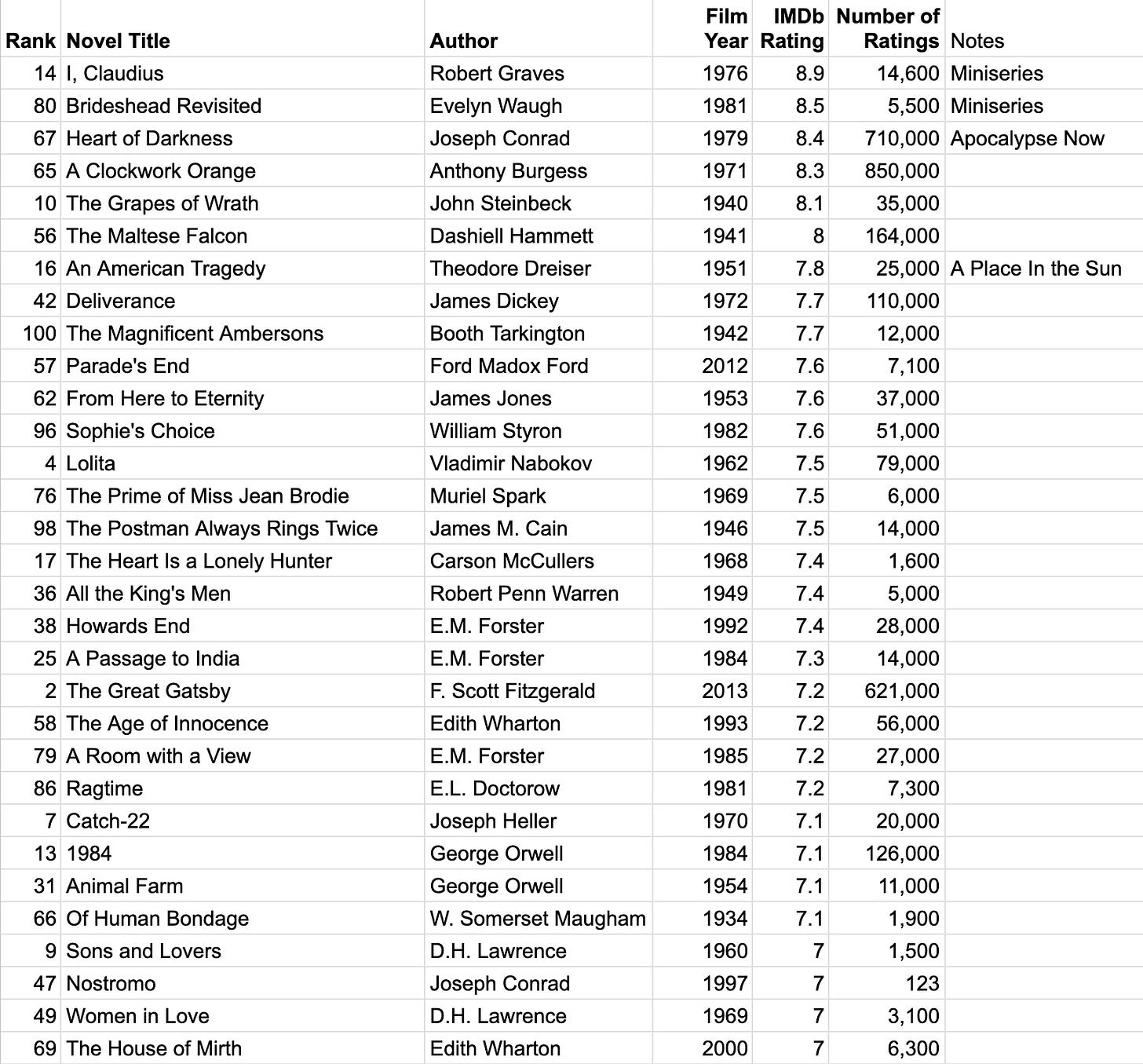

Below, I will list the 74 top novels that have been made into films as rated by Internet Movie DataBase enthusiasts. If the book has been filmed more than once, I used the version that got the most IMDB ratings (e.g., Leonardo DiCaprio’s Gatsby rather than Robert Redford’s).

One big advantage of IMDB ratings are giant sample sizes, up to 3 million ratings for The Dark Knight and The Shawshank Redemption. One disadvantage is that the pool of raters is strongly biased toward young men who really like The Dark Knight and The Shawshank Redemption.

The latter, which is based on a Stephen King novel (King did not make the Modern Library list) is the highest rated film in IMDB with a 9.3 on a 1 to 10 scale.

Another issue is that the colossal sample sizes are mostly for color movies made in recent decades. 1930s classics will tend to have under 100,000 ratings. For example, John Ford’s 1940 black and white The Grapes of Wrath with Henry Fonda has 35,000 ratings (8.1), the 1935 A Tale of Two Cities with 6,600 ratings (7.8), and George Stevens’ 1939’s Gunga Din with Cary Grant has 13,000 (7.2, that seems kind of low, perhaps due to increasing South Asian bias).

But those are still huge sample sizes.

IMDB raters tend to overrate recent movies, but the ones who rate old movies are quite knowledgeable, so a 7.5 is almost certainly better than a 6.5.

So, the ratings mostly are plausible, other than some of the more fanboyish ones.

For example, IMDB’s second highest rated movie at 9.2 is 1972’s The Godfather. Is The Godfather one of the two best movies of all time? Probably not, but it’s also about as reasonable a nominee as you can come up with. (It’s like I said when Willie Mays died: Was Willie the greatest baseball player ever? Probably not, but he’s also just about the least crazy choice you could put forward.)

In general, on the IMDB list, 9s are stratospheric (only 7 at present), 8s are all time greats (there appear to be several hundred 8s), 7s are quite good movies, 6s are pretty goods to not bads, and 5s are mediocre.

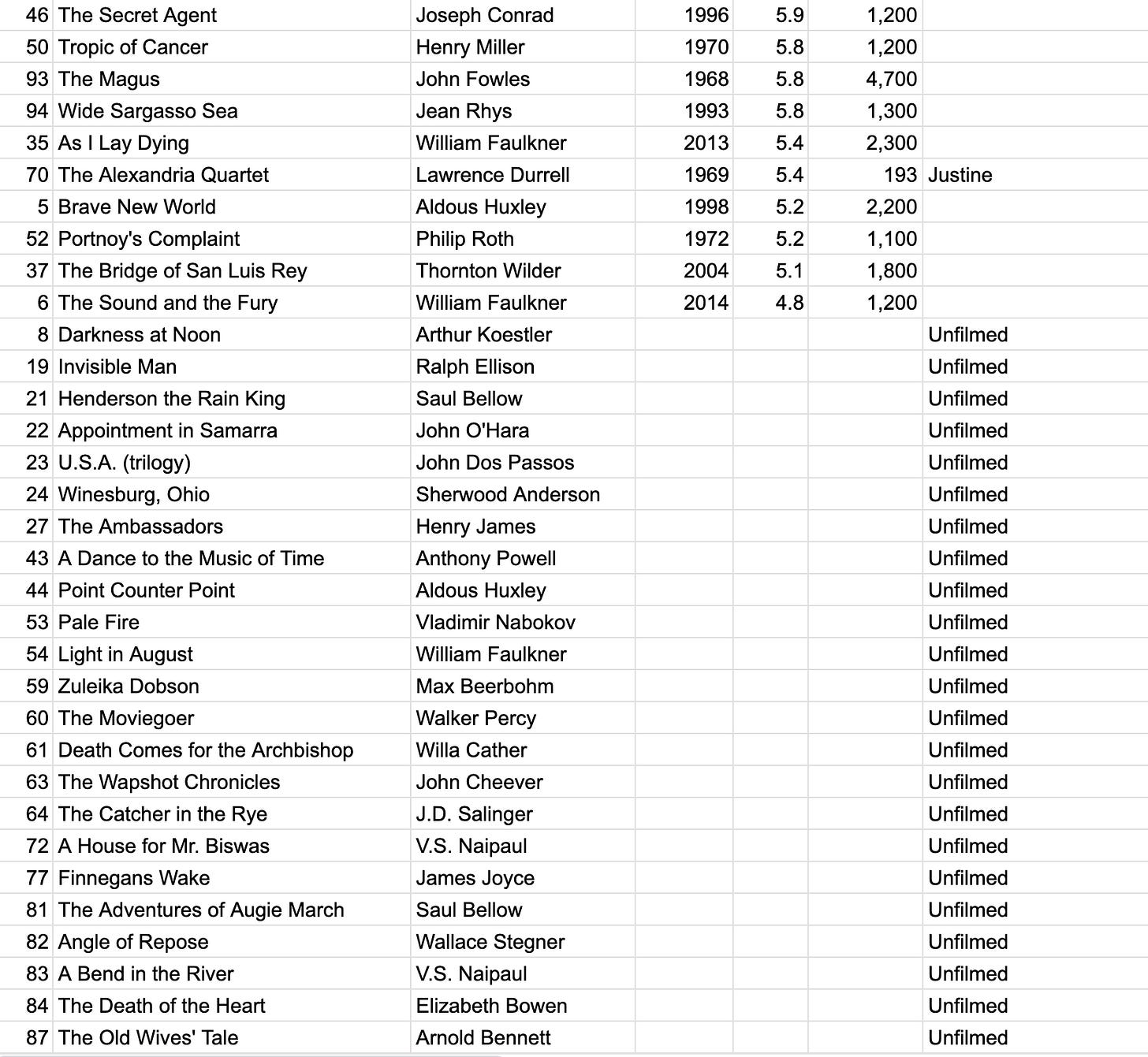

For some reason, Substack doesn’t make it easy to post tables (there are ways, but this old dog doesn’t learn many new tricks), so I’m going to post the top 100 novels list ranked by IMDB rating divided up into four screenshots:

So, after a lot of boring methodological quibbles, I’m finally going to reveal the top 100 novels and their movie adaptation IMDB ratings!

Except … I’ve got to make a living. So, here comes the paywall. After it there are the top 100 rankings plus 1,260 words of text.

The two highest ranked fiction adaptations, Robert Graves’ I, Claudius and Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, are actually television miniseries, as are Parade’s End by Ford Madox Ford (Hueffer) and Nostromo by Conrad. People these days really like Prestige Television. It’s a little slow for my tastes compared to the velocity of telling a complex story in a two hour film. But, then, I get bored easily.

After the top two miniseries, four films based on top 100 novels make the 8s: France Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Stanley Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange, John Ford’s Grapes of Wrath, and John Huston’s Maltese Falcon.

Basically, it looks like a great director has more impact on how great a two hour film can be than a great novelist.

As the movie business joke goes, the blonde actress was so dumb that she slept with the screenwriter. (In contrast, playwrights are The Man due to their contractually having final say over all productions of their plays. Thus, Marilyn Monroe married Arthur Miller.)

Novelists who wrote the screenplay for the adaptation of their Modern Library novel that scored 7.0 on IMDB or above include Anthony Burgess for Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange, James Dickey for John Boorman’s Deliverance, and Vladimir Nabokov for Kubrick’s Lolita (although word is that Nabokov’s unfilmable script was massively rewritten). That’s not a huge list.

The movie adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness was of course Apocalypse Now. Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy was filmed under the title A Place in the Sun.

The Maltese Falcon’s 164,000 ratings is a huge number for a black and white film from the first half of the century. Others with even more ratings include Casablanca, It’s a Wonderful Life, Citizen Kane, The Best Years of Our Lives, and Sunset Boulevard. It’s neck and neck and neck with The Third Man and Double Indemnity for most often rated crime noir films. (So, if you want to sound informed about old time black and white films that are still talked about, those aren’t bad ones to start with.)

I was rereading Styron’s Sophie’s Choice recently, but I stopped after 100 pages because rather than spending 25 hours reading the book or whatever it would take, it would make more sense to spend 2.5 hours watching Meryl Streep and Kevin Kline act out the dialog better than I can hear it in my head.

Now we are getting into the pretty good movies, but in which the film is almost always less famous than the Modern Library ranked book. I’m having a hard time remembering whether or not I saw some these movies, and if I do, I can mostly remember a few scenes.

For example, Ironweed by William Kennedy, who was a big deal writer in the 1980s, was a fine 1987 movie that didn’t quite live up to its cast of Jack Nicholson (12 Oscar nominations) and Meryl Streep (21 Oscar nominations). But I recall being astonished when Streep, who had mostly played dramatic if not tragic characters in the first dozen years of her movie career, suddenly launched into a song and dance number, the first of her hammy but massively entertaining second act of her career.

Likewise, I mostly remember the 1988 version of Waugh’s Handful of Dust for Anjelica Huston’s small role that went in the opposite direction. She was entertainingly playing a satirical role as an American aviatrix, but when tragedy befalls the main character, she’s suddenly extraordinary kind. I can recall thinking that if anything that bad ever happened to me, I hope Anjelica Huston would be hanging around at the time.

Still, these are quality films that were satisfying to see theaters. It’s just hard to remember them three dozen years later.

The median rating of the 74 filmed versions is 6.8, which is not at all bad, but not the slam dunk the people who made and greenlighted these movie probably expected.

Various sources say the median or average rating for all movies on IMDB is 6.6, 6.7, 6.9, and 7.0. That seems high. Perhaps that is weighted by rating rather than by movie (i.e., 8s get more ratings than 4s)? There are a lot of misbegotten movies that are forgotten. Making a good movie is hard and a lot can go wrong even if you are starting from a classic novel, as you can see below:

The 5s are pretty bad.

The most famous of the unfilmed books is The Catcher in the Rye, which J. D. Salinger objected to ever having filmed.

Others seem unfilmable, like Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (a madman editor’s hilarious endnotes to a poem).

And other books have never been filmed for … reasons, such as John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces (which didn’t make the Modern Library list), which is so funny it first went into development hell before it was published in 1980, but has never quite made it to the screen. After all is said and done in Hollywood, more is said than done.

Among the 74 film movies, there is no zero correlation between their Modern Library ranking and their IMDB ranking. But that’s not surprising. All the ranked novels are really good in one way or another out of the tens (hundreds?) of thousands of novels published in the 20th Century.

In case you are wondering why Arthur Koestler’s anti-Stalinist Darkness at Noon is listed as an English language novel when it was written in German, that’s because the German original draft was lost in the first days of the Fall of France in 1940, so the book was first published in an English translation by Koestler’s 21-year-old English girlfriend. The German manuscript was finally rediscovered and published in the last decade.

In the future, I will turn this analysis around and look at lists of top movies to see how many were based on famous novels. My guess is that a lot of famous movies were based on obscure novels or true-life books.

The basic problem with adapting great books is that a high quality literary prose style in the narration does not directly translate into a high quality film other than by inspiring high quality cinematic artists to do great work on its adaptation.

For example, I can’t stand Conrad’s prose style in Heart of Darkness (although I quite enjoyed it in Lord Jim), but obviously it enthralled Coppola and John Milius.

Occasionally, great dialogue translates into a great movie. For example, The Maltese Falcon had been twice adapted into lousy movies when Huston had his secretary go buy two copies of the novel and paste each page onto a blank sheet of paper. He just crossed out stuff, had her type it up, and got the go-ahead.

The Maltese Falcon makes the Modern Library list because of its colossal effect on American culture.

Similarly, the Coen Brothers have seldom adapted a work of fiction rather than writing their own pastiche for their own purposes. But when they do, as in Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, Charles Portis’s True Grit, and, most astonishingly, the great wagon train segment in their The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, they just adapt faithfully. Unlike McCarthy and Portis who are clearly great writers, I’d never heard of the author of the 1903 Western short story “The Girl Who Got Rattled,” Stewart Edward White. But the Coens just used his dialogue just word for word.

But, you have to be as sharp as the Coens to anticipate what will translate to the screen.

As a devotee of the Patrick O'Brian Aubrey-Maturin novels, twenty in all, I would like to see more than the O'Brian stew that is the film "Master and Commander", made in about 2003. I wish it was made into a mini-series but it will never happen. Hollywood is more into the fast profit and most people haven't read O'Brian.

Much as I hate them both, Lolita and especially Clockwork Orange do justice to their novels. I'm surprised World According to Garp doesn't make this list. I'm also surprised that a John O'Hara book was made into a film: he is one of the most under-rated novelists of his time, and the novels seem well-suited for adaptation. There are many more surprises on the list: thank you for making it.

Deliverance is the worst film adaptation of a very good book, of the ones I know here. I knew Dickey at the end of his life and planned to write my dissertation about him and Updike, the finest writer of the century, but could find no interested sponsors for a work on white men "like that." Updike happily avoided Hollywood after the unspeakably wretched Witches of Eastwick, but I'd love to see a quality Rabbit miniseries. Dickey was an excellent poet; Deliverance, the book, is a complex rendering of real events -- not the rape -- the fraught relationship between mountain folk, Atlanta's contempt of them, yet rapacious desire for their water. A better movie version would feature the making of the movie itself. Life certainly challenged art. William Redden, the "inbred albino banjo player" is none of these things. Dead Robert Redford would be thrown into Talluha Gorge had he ever returned to Rabun County, where the people are neither stupid nor inbred and deeply resented being characterized that way.