Latest Rationalization: Race Doesn't Exist, But Subraces Do

It's tough being a human scientist trying to not get cancelled for knowing that races do exist, so be kind.

Most every field of study, whether scientific or humanistic, witnesses disputes between lumpers and splitters, a distinction that traces back to a letter written by Charles Darwin in 1857: “

Those who make many species are the ‘splitters’ and those who make few are the “lumpers.”

Who is right, lumpers or splitters?

I dunno.

In general, both tendencies can be useful under different circumstances.

For example, are you against building hydroelectric dams?

Then, splitting out the small snail darter fish as a separate species protected by the Endangered Species Act, as a natural history professor and opponent of the construction of the Tellico Dam did in the 1970s, is good.

On the other hand, a Yale lumper academic recently disputed that distinction.

One of the more subtly amusing intellectual trends in the current era is human scientists, such as geneticists and forensic anthropologists, who are of the splitter tendency regarding racial categories are lately exploiting the lowbrow Race Does Not Exist conventional wisdom to denounce as racists their colleagues of the lumper tendency who find the federal Office of Management & Budget’s lumpy categories (e.g., black, white, Asian, American Indian, etc.) to be good enough for government work.

It’s pretty strange to see splitter race scientists going all Hakan Rotmwrt on the race deniers by agreeing and amplifying: Right, just as you say, continental scale races like “Asians” are unscientific, therefore we need instead to officially break out precise populations like “Japanese” and “Hmong!”

But it’s weirder to see race deniers agreeing: Uh, yeah, Asians aren’t a Thing, but Hmongs are a Thing. The Science has spoken!

Splitting has its advantages … but it also shows how confused everybody is over race and how easy it is to fool true believers in the conventional wisdom.

For example, from Science in 2021:

Forensic anthropologists can try to identify a person’s race from a skull. Should they?

Debate over “ancestry estimation” has exploded in forensic anthropology

18 Oct 2021 3:35 PM ET By Lizzie Wade

As they work to identify human remains, some forensic anthropologists are wondering whether they should continue to use racial categories.

When an unidentified body arrives in the laboratory of Allysha Winburn, a forensic anthropologist at the University of West Florida, it’s her job to study the bones to help figure out who the person was when they were alive—to give the biological remains a social identity. “We have this vast population of possible missing persons the [remains] could match, and we need to narrow down that universe,” she says.

Forensic anthropology, a branch of physical or biological anthropology, helps humanity by identifying dead bodies and assisting in bringing murderers to justice. It was fashionable earlier in this century with all those CSI shows.

In the long run, scientists who measure bones and skulls to get preliminary estimates of which missing persons to rule out by being the wrong height, age, sex, and race (reducing the number of possible matches is is a huge help to detectives), might eventually be displaced by geneticists trained in the advanced techniques of ancient DNA researchers like Nobelist Svante Paabo and David Reich.

But, contamination by outside DNA is a huge concern, and it’s more likely in crime investigation than in digging up ancient graveyards.

Say that construction workers accidentally start digging in what turns out to be an ancient cemetery. They dig up one skeleton and get their DNA all over it trying to figure out whether it was an animal or a human before deciding the latter and dutifully calling the authorities.

If it turns out that it’s just the first of 100 skeletons in this Bronze Age graveyard or whatever, well, 99% of the bodies are still buried and uncontaminated. Grad students can then carefully dig the rest up using all the latest expensive anti-contamination techniques.

But if it’s a lone murder victim, then 100% of the bodies of interest have already been contaminated with outside DNA.

So, bone and skull measuring is likely to remain a major tool in crime scene investigations.

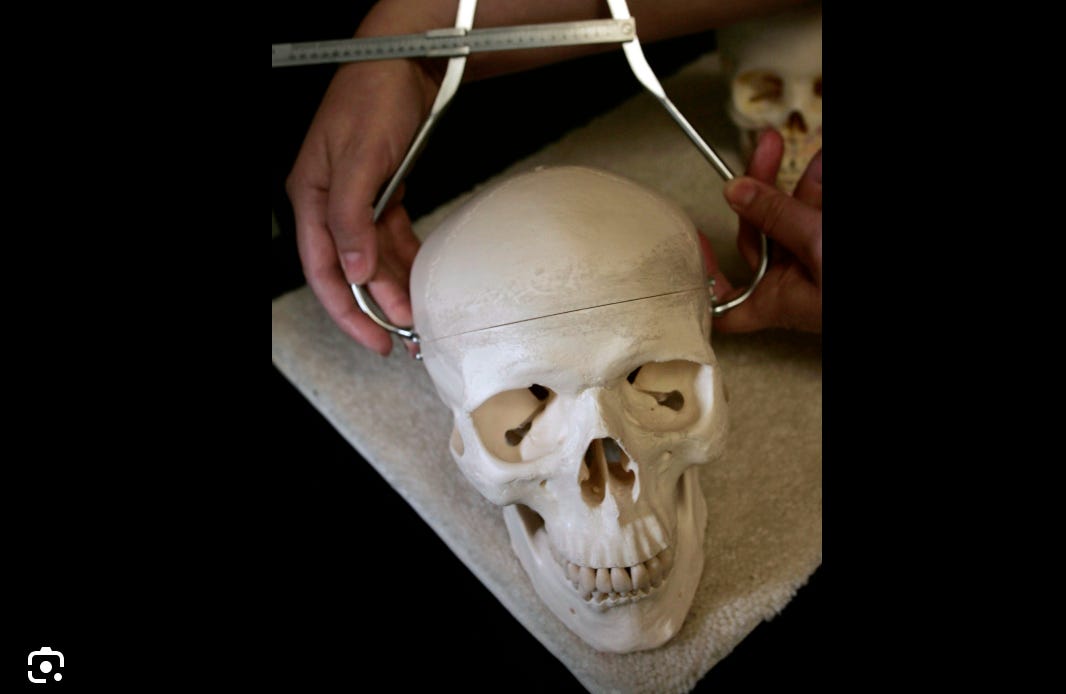

She measures the length of the limb bones to estimate height and examines the bones’ development to estimate age at death. She studies the shape of the pelvis for clues to the person’s likely sex. And, until recently, Winburn measured features of the skull, such as its overall length and the width of the nasal opening, to do what forensic anthropologists call ancestry estimation. By statistically comparing the measurements with those from skulls with known identities, she could predict the continental ancestry—and the commonly used racial categories that may correspond to it—that a person likely identified as when alive. In other words, she could predict whether they identified as Black, white, Hispanic, Asian, or Native American.

Unfortunately, forensic anthropology’s main tool has always been the calipers, currently the world’s most uncool scientific instrument. As everybody just knows these days, calipers are tools of racist pseudoscience. Skulls can’t possibly differ statistically by race. After all, The Science has spoken.

Not surprisingly, forensic anthropology scientists have been scared for their jobs during the Racial Reckoning.

But Winburn, who is white, is now questioning whether she should continue to do so. And she’s not the only one: Over the past year, debate about ancestry estimation has exploded in U.S. forensic anthropology, with a flurry of papers examining its accuracy, interrogating its methods, and questioning its assumptions. A committee of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences’s standards board is now hammering out a new standard that would, if adopted, direct professionals away from racial categories and toward more specific social and biological populations, such as Japanese or Hmong instead of Asian.

Okaaaaay …

To you and me, obviously, when a crime scene investigator reports that a skeleton is Asian, he’s more likely to be right than when he reports that it is Japanese. But to a remarkable number of fairly influential people, that isn’t second nature to think like that at all.

They have a very different assumption about what “scientific” means, which I will get to after the paywall.

Paywall here.

… Two biological and forensic anthropologists ignited the latest round of debate in the summer of 2020,

After all, every idea put forward with passion in the summer of 2020 was pure science.

in a letter to the Journal of Forensic Sciences. Jonathan Bethard of the University of South Florida and Elizabeth DiGangi of Binghamton University argued that ancestry estimation remains dangerously tangled up in its racist roots. Many of today’s forensic anthropologists were trained to identify race using the same techniques earlier generations of scientists employed to argue for biological differences and hierarchies among races in the “race science” of the 19th and 20th centuries. Today’s anthropologists now know those scientists were wrong both biologically and ethically.

If they were wrong biologically, why does their invention work pretty well today?

But translating skeletal data into race, a socially determined category, still reifies the erroneous notion that race is biological, Bethard and DiGangi argue.

If the techniques of biological anthropology work pretty well to identify the racial ancestry of a skull, then, evidently, racial ancestry must be somewhat biological.

But that’s because the skull has forgotten it’s Stephen Jay Gould, who wrote a quadrillion words of sonorous prose about how reifying race is, a priori, wrong. So if serious professionals are using race as a factor in helping them give closure to people wanting to know what happened to their loved ones, well, then, those grieving relatives are just going to have to tough it out because to use biological science to help people find out the truth about their relations is just going to have to take a backseat to the upholding the infallibility of Stephen Jay Gould and his believers.

Or something.

“Ancestry estimation is race science, pure and simple,” says DiGangi, who is Black and biracial.

How can she tell?

The pair also wrote that the criminal justice system might give less attention to remains when they are classified as members of marginalized groups. [“We can’t] assume that our work is not harmful,” says Bethard, who is white. The pair urged forensic anthropologists to stop performing ancestry estimates and study whether the practice results in discrimination.

More likely, ruling out a lot of the possible Missing Persons by race elicits more attention from the cops to any particular case since their task now seems less hopeless.

The letter triggered an explosion of debate. “It took a lot of courage for them to put that letter out,” says Kyra Stull, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Nevada, Reno. “It’s been a catalyst for a lot of positive change.”

But Stull disagrees with Bethard and DiGangi, co-authoring a response to the article that argues ancestry estimates are important tools. “Right now, the reality is that social race is part of how people identify in the United States, and that follows them [in death],” says Stull, who is white.

I suspect the journalist was starting to get in on the joke by this point.

Race is included in missing persons reports, police case files, and in almost every other description of a person. “That has to change for [ancestry estimation] not to be useful.”

Uh, yeah…

That’s how missing person reports are categorized: Asian, black, white, etc.

Also, lots of times witnesses make reports using general racial categories: e.g., “I saw two white men forcing an Asian woman into an SUV.”

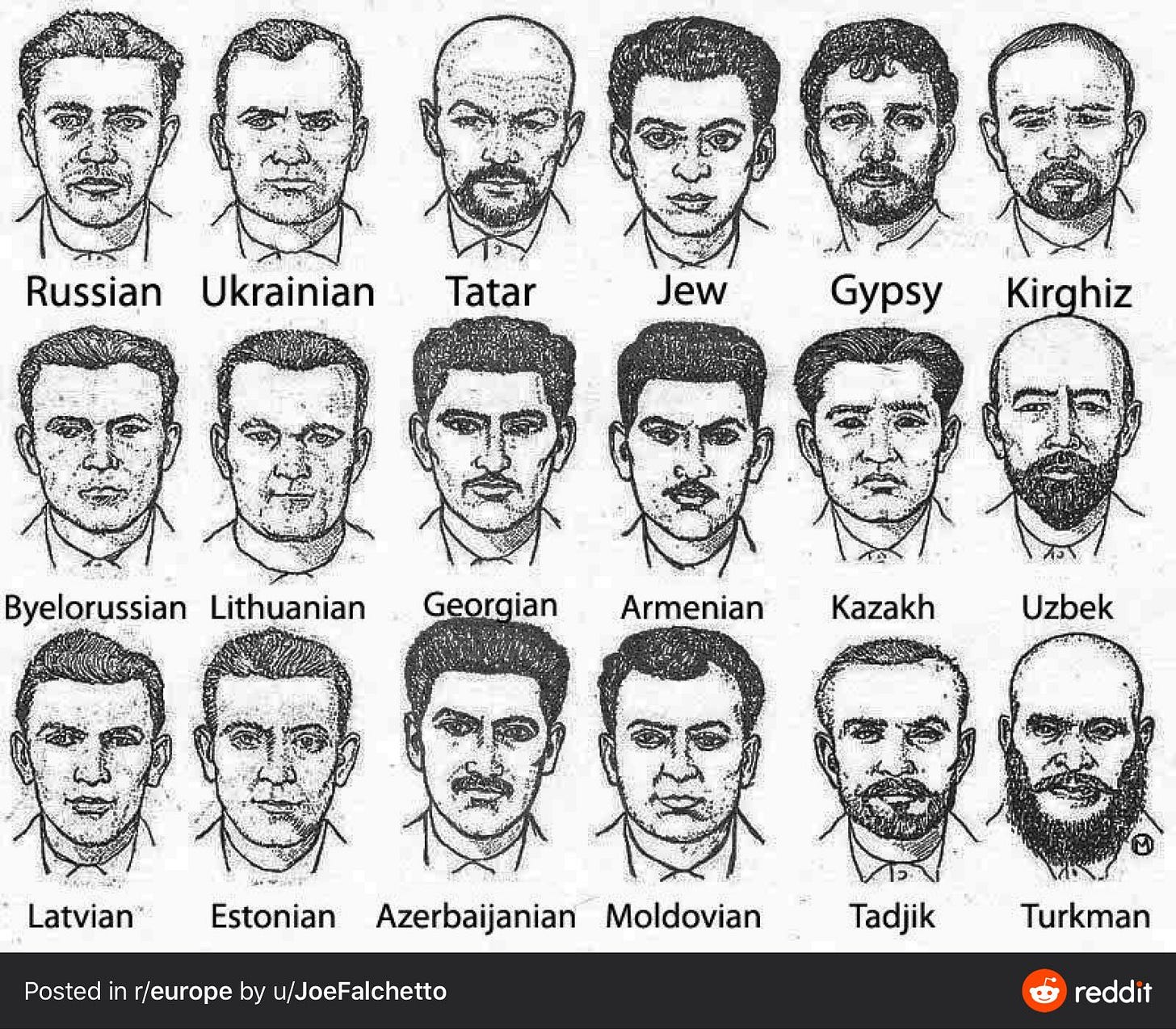

It would of course be more helpful if witnesses would accurately state, “I saw a Byelorussian man and a Latvian youth forcing a Samoyed woman into a ZiL,” but the 99% of white Americans who don’t play EthnoGuessr mostly are vague on such now politically incorrect categories.

“Many of the unknown individuals that come to us are from disenfranchised populations,” adds Williams, who is Black. “When you take off the table a parameter that could help somebody get home to their family … then it’s not the greater good.”

Right.

Personally, I’m in favor of using science to help families with missing loved ones find out the truth.

But then I’m a notorious Bad Person.

At this point, good old Agustin Fuentes can’t resist jumping in:

The fact that ancestry estimation sometimes works “does not in any way, shape, or form mean that [races] are biological categories,” stresses Agustín Fuentes, an anthropologist at Princeton University who is Hispanic and white.

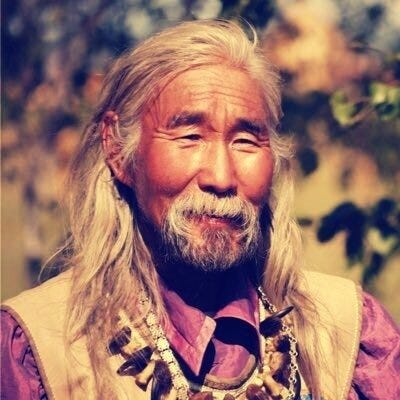

Fuentes, whose father is from Spain and whose mother is from New York, could be played in a movie by Daniel Day-Lewis, whose father was the Poet Laureate of England:

There’s no checklist of skeletal, physical, or genetic traits shared by all people of a certain race; in fact, there’s far more variation within racial categories than between them.

At the same time, “We’re all a product of our environment, evolution, and history,” says Ann Ross, a forensic anthropologist at North Carolina State University. People who share both deep evolutionary history and more recent social contexts, such as an industrial lifestyle or a history of discrimination, tend to also share some biological traits, including similar cranial measurements. She and some other anthropologists wonder whether current ancestry estimates are accurate enough to be helpful.

So now we are getting from Race Does Not Exist Biologically science deniers to the splitters who say that Race Does Not Exist Biologically Because Subrace Exists Biologically.

Winburn and a colleague did a study to try to find out. Among about 250 resolved cases in which forensic anthropologists offered an ancestry estimate, they correctly identified a person’s social race about 90% of the time, the team reported in April in the Journal of Forensic Sciences. But when anthropologists identified someone’s ancestry as “mixed” or “other,” they were wrong 80% of the time. Thirteen percent of unidentified people in the United States are listed as likely belonging to “multiple races”; another 21% are classified as “uncertain.” Based on her research, most of them are likely to be people of color, Winburn says. “Who are we serving and who are we failing with these continental ancestry estimates?” she asks.

It appears that forensic scientists are quite accurate when they do report a race, but they are also cautious and don’t want to get race wrong, so they don’t guess definitively when they aren’t very certain, even though it usually turns out that the ambiguous murder victims are black or Hispanic.

Some forensic anthropologists who want to jettison the five commonly used racial categories say skeletal features could let them make more specific and useful distinctions. For example, cranial measurements can distinguish between Maya groups from Guatemala and Mexico and differentiate each from non-Maya people, according to a February study in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Such specificity could help identify people who die crossing the U.S.-Mexico border, the study argued.

Yeah, it definitely would.

But ultra-precise estimates like this also increase the chance of getting it wrong, with unfortunate consequences. Imagine:

“Ma’am, this is Detective Smith with the Tucson Police Department. I see you filed a missing person report for your brother, Jose Gonzalez, age 35, 5’4”. I’m sorry to say that a dead body, male, 5’3”, age 30 to 40, has been found in the desert. By any chance, is your brother of Guatemalan Mayan descent?”

“A Guatemalan Mayan? Of course not! We Gonzalezes are 100% Mexican Mayan.”

“My apologies, Ma’am. We won’t be bothering you again.”

And see what I mean about going all Hakan Rotmwrt as an end-run around the Race Does Not Exist fad?

The United States’s traditional racial categories don’t reveal such potentially informative variation—they obscure it, Ross says. People from any population in Mexico, Guatemala, and the rest of Latin America—as well as many populations in the United States—are all classified as “Hispanic,” a label Ross, who is from Panama, calls “biologically meaningless.”

“Hispanic” is supposed to be an ethnicity, not a race, as several Census forms I’ve filled out have stated. We would be less confused if we used Spanish terms for Latin American racial realities such as “mestizo” and “mulatto.” But Americans think those are racist.

The proposed standard, which Ross is helping draft, will reflect that concern, promoting the use of “population affinity estimates” that refer to more specific social and biological groups.

In the meantime, Winburn won’t provide ancestry estimates until and unless she can take a population approach that doesn’t focus on reductive racial categories. She no longer wants to risk using a tool that she thinks may do more harm than good.

This has baffled me for a long time, but now I think I grasp what is going on: A lot of people assume that “scientific” is a synonym for “precise.” Thus, to much of the public, it’s not scientific to say: “This skeleton appears to be Asian.” But it is scientific to say: “This skeleton is Hmong.”

Similarly, from Nature this week:

COMMENT

24 April 2025

Eugenics is on the rise again: human geneticists must take a stand

Scientists must push back against the threat of rising white nationalism and the dangerous and pseudoscientific ideas of eugenics.

By Genevieve L. Wojcik

… Meanwhile, although Trump stated at his inaugural address that his administration “will forge a society that is colorblind and merit-based”, an executive order he signed in March condemns as “corrosive ideology” the Smithsonian Institution’s promotion in its museums and research centres of the view that race is not a biological reality, but a social construct.

As I’ve pointed out now and then, everybody has a family tree. Your ancestry exists in this weird Platonic sense like triangles exist. But family trees rapidly become enormous. If you go back 40 generations to 800 AD, Europeans almost certainly have Charlemagne in their family tree. But you also have about a trillion slots to fill in your family tree so nobody has all that ideal of a rule of thumb for how to summarize the contents of your trillion slots.

Different cultures socially construct different rules of thumb for summarizing family trees. Some go with paternal line ancestry, while Jews for the last 2000 years have gone with maternal line ancestry (although ancient Hebrews in the Bible were very much into their male lines of descent, as in the New Testament begats). Others go with the bulk of their ancestry.

… But the latest wave of white nationalism is happening after decades of two interlinked concepts gaining attention and acceptance in the scientific community.

On the one hand, there is broad consensus among researchers that social constructs of descent-based identity, such as race and ethnicity, do not align with genetic groupings.

When you say they “do not align with genetic groupings” are you claiming that they don’t correlate at all, 0% … or merely that they correlate less than 100%? I presume that, if challenged, being a genetics professor, you’d fall back to the ho-hum latter, but as an activist you don’t mind that large numbers of people assume The Science has proven the former, which of course you know isn’t true at all, but you’re not going to go out of your way to make that clear.

On the other, there is growing awareness that diversity matters for sound science and effective policy, including in health care. Embraced together, these two concepts have strengthened science and increased benefits to health.

More logically, the two ideas are contradictory.

How can you tell if your people are sufficiently diverse if you can’t ask people to check a box attesting to their race?

Race as a social construct

Decades of sociological data demonstrate that racial and ethnic identities, whether self-identified or otherwise, are constructs that are defined and deployed in specific sociopolitical contexts.

Take the degree to which racial and ethnic categories have been altered over the past two and a half centuries in the US Census, in response to political needs and social changes.

This article is more intellectually sophisticated than most. It doesn’t assert that today’s racial categories are due to fallacious “folk wisdom,” but vaguely acknowledges instead that they are the result of post-Civil Rights politics within the federal government.

The term Hispanic, which is now used to refer to people with heritage from Spanish-speaking countries, was first brought in for the 1970 census, in response to lobbying from Latino advocacy groups.

And for decades, Census forms made clear that Hispanic was an ethnicity rather than a race. You could pick any race you wanted and still pick the Hispanic ethnicity.

After all, over the last half century, Democrats have run the Office of Management & Budget for 24 years.

My impression is that the Biden Administration junked that for the 2030 Census, but perhaps geneticists should have organized a protest?

In reaction to changing societal norms, the term African American was added to the 2000 census as an alternative to ‘Black’ and ‘Negro’ (with the latter being dropped in 2013, in time for the 2020 census).

This example is particularly unimpressive since those are just different names for the same race. A particularly crucial discovery of 21st Century genetics has been that the distinction between the billion plus sub-Saharan blacks and 7 billion Out-of-Africans is the main genetic division within the human race at present.

Alongside analyses of sociological data, genetic research has repeatedly demonstrated that constructs of descent-based identity, such as race and ethnicity, do not align with discrete biological groupings.

And what does “discrete” mean here?

It has also shown that their use can exclude those who do not fit into a specific category and obscure substructure in populations, with implications for human health.

“Obscure substructure in populations” means having more racial groups.

For example, the likelihood of people having haemoglobinopathies (inherited disorders that affect red blood cells) varies substantially depending on where in the world a person lives. In some regions of India, carrier rates for the blood disorder β-thalassaemia are estimated to be higher than 8%, whereas in areas of China, they can be as low as 2.7%4. This heterogeneity would be missed if researchers simply grouped study participants as ‘Asian’, a term that refers to nearly 60% of the global population.

As I may have mentioned once or twice over the decades, lumping together East Asians and South Asians was done during the Carter Administration in order to expand the number of nonwhites getting racial preferences.

Lumping East Asians and South Asians together was convenient due to the then Tyranny of the 8.5” x 11” Piece of Paper. The Office of Management & Budget was highly cognizant of the need to limit categories to squeeze racial checkboxes into a limited size sheet of paper.

As we increasingly go all electronic, it would make sense to separate East Asians and South Asians.

Similarly, using the category ‘Hispanic’ without considering other factors would fail to reveal that the genetic variant associated with Steel syndrome, a rare genetic bone disorder, is more common in people from Puerto Rico than in those from the Dominican Republic or Mexico.

See what I mean about the Revenge of the Splitters?

Many now question the use of race as an appropriate proxy for anything, from hypothesized biological differences to environmental influences. In fact, researchers and health-care providers have been moving away from ‘race-based medicine’, in which perceived biological differences change the estimation of clinical risk and the provision of patient care on the basis of whether people are Black, white, Asian, Hispanic and so on.

Counter the weaponization of genetics research by extremists

In conjunction with the growing acceptance of the idea that social identities related to ancestry don’t align with genetic groupings, multiple studies conducted over the past decade have demonstrated the benefits of including diverse participants in research.

Uh, OK, but how are you going to find “diverse participants” without asking them to check a race box?

Any two human genomes are, on average, more than 99% identical. Yet millions of variants across people’s genomes — including ones that are relevant for health — differ in frequency to varying degrees as a result of demographic processes (both random and non-random) playing out over centuries to millennia.

“Demographic processes” such as evolution on different continents.

Increasing the diversity of participants in studies increases geneticists’ chances of finding variants that are important to health, and lessens their likelihood of drawing spurious conclusions about the genetic or other factors driving disease.

The availability of large-scale multimodal data and advanced statistical and computational tools is making it easier than ever for researchers to stop relying on race or ethnicity as proxies for biology or structural and social determinants of health. Instead, they can interrogate the effects of many well-defined variables, from people’s genetics and geographical location to their diet and income.

Uh, no, testing genetics is expensive and slow, so clinical trials rely on volunteers checking boxes about which race they are, which seems to work good enough.

Consider Moderna’s covid vaccine trial in 2020. In late summer 2020, Moderna, which was subsidized by the first Trump Administration’s Operation Warp Speed, was on track to have announced, at the latest, by Monday November 2, 2020, the day before the election, that Trump’s Operation Warp Speed had achieved vaccine efficacy, probably re-electing Donald Trump. But then the Trump Administration’s FDA insisted that Moderna pause its clinical trial and recruit more patients who checked boxes as racially nonwhite. Thus Moderna only announced its highly successful results 13 days after the election, which Trump could have won by flipping less than one half of one percent of voters.

The Hispanic designation is a rainbow stew united mostly by the ability to speak Spanish. At my church, we have three Hispanic families. One is a divorced white Cuban man whose family were big landowners in Cuba until Castro gave them the boot and expropriated their land. He became a CPA. He speaks perfect English and Spanish. Another is a mestizo Salvadoran man who immigrated during the Civil Wars of the 80s. He drives a trash truck. He speaks perfect English and Spanish. He is recently divorced from his white wife. The last is a family with five children. Both the man and his wife are short, squat and are from El Salvador. Both speak poor English. Both probably are heavily Indian in heritage. He's a handyman for an apartment complex. All are very different Hispanics. But they share a category.

so, the apostrophe makes this pretty funny:

"the skull has forgotten it’s Stephen Jay Gould"