P.J. O'Rourke on Somalis

A portrait of the future Minnesotans in their native state.

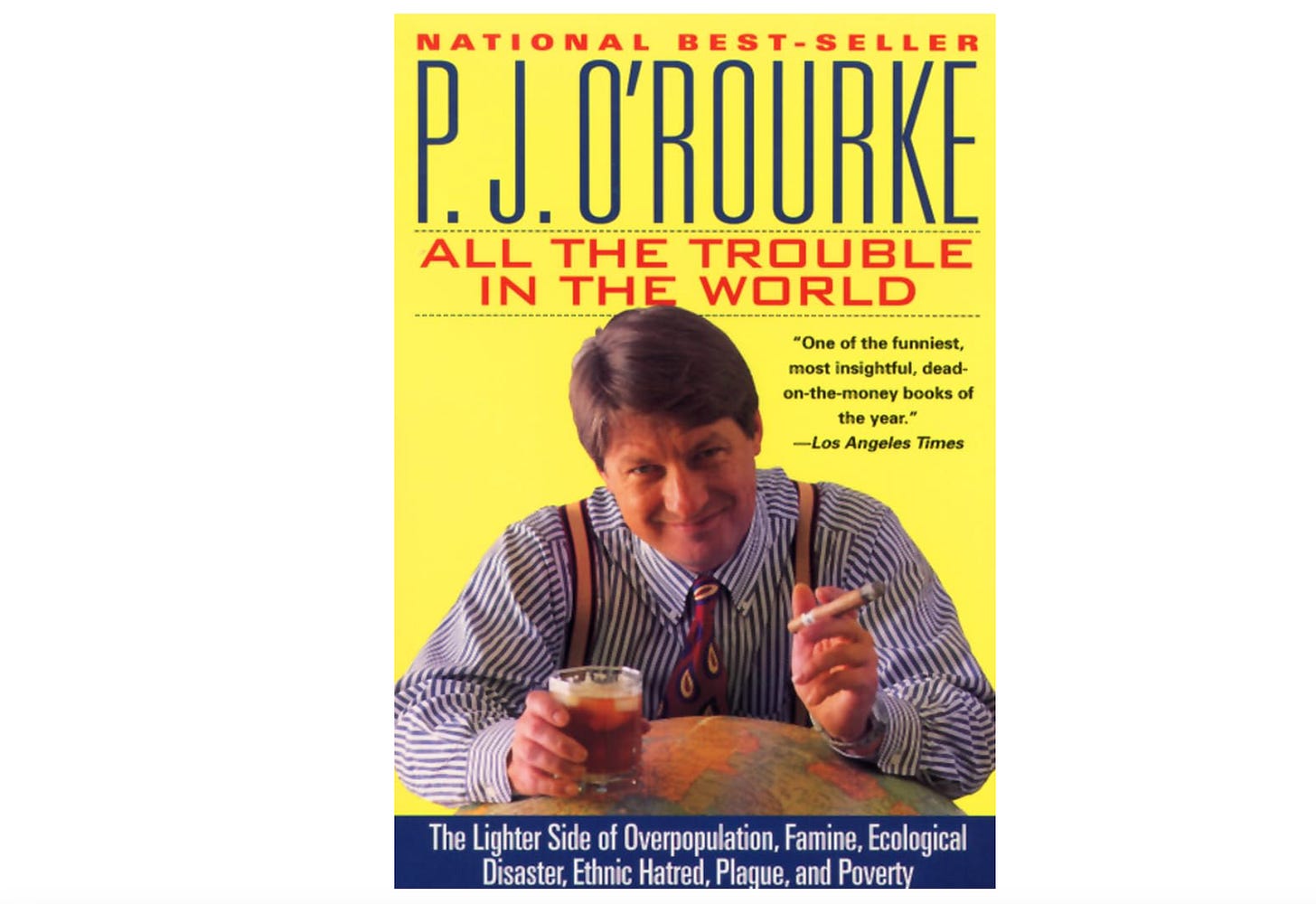

With Somalis much in the news, I recall that satirist P.J. O’Rourke visited Somalia in December 1992 when the U.S. military brought food relief and wound up fighting the Black Hawk Down incident with a clan chief who had wanted to be on our side. Here are excerpts from the late P.J.’s essay in his book All The Trouble in the World:

FAMINE

All Guns, No Butter

I went there in December 1992, shortly after U.S. troops had landed in Mogadishu.

,,, And in Somalia the good intentions that professional worriers forever profess were being combined with—how rare this mixture is—good deeds. Food was being shipped to the country and international peacekeepers were being sent to deliver the food.

“Feed the hungry” is one of the first principles of morality. Here it was in operation. So where were the starving children of Mogadishu? …

What I met with instead were guns. Arrayed around the landing strip were U.S. guns, UN guns, guns from around the world. Trucks full of Somalis with guns came to get the luggage. These were my guns, hired to protect me from the other Somalis with guns, and they all had them. And I thought I might get a gun of my own besides, since none of these gunmen—local, foreign, or supranational—looked like they’d mind shooting me.

Everything that guns can accomplish had been achieved in Mogadishu. For two years the residents had been joining, dividing, subdividing, and rejoining in a pixilation of clan feuds and alliances. Previously Somalia had been held together by the loathsome but stable twenty-two-year reign of dictator Siad Barre. But Barre gained loathsomeness and lost stability, and when he took a walkout powder in January 1991, all and sundry began fighting each other with rifles, machine guns, mortars, cannons, and—to judge by the look of the town—wads of filth.

No building was untouched, and plenty were demolished. It was a rare wall that wasn’t stippled with bullet holes and a peculiar acre that lacked shell damage. Hardly a pane of glass was left in the city. There was no potable water and no electricity. At night the only illumination was from tracer bullets. Mogadishu’s modern downtown was gone, the steel and concrete architecture bombarded into collapse. …

It’s easier to advertise our compassion for innocents in misery than it is to face up to what happened in a place like Somalia. What happened was not just famine but the complete breakdown of everything decent and worthwhile. I spent two weeks in Somalia and never saw a starving child, not because they didn’t exist but because they were off somewhere dying, pushed into marginal spaces and territories by people with guns. Going to Somalia was like visiting the scene of a crime and finding that the murderer was still there but the body had fled.

… Nonetheless, for someone who has been to Somalia, Mr. Cohen’s views sail precariously close to Romantic primitivism. Mogadishu is no place to argue in favor of Rousseau’s ideas about “natural man.” Attribute superior virtues to simple natives, if you will, but the Somalis are about as untainted by civilization as they could be, and no one who’s met the Somalis is calling them noble savages.

III

In order to go to Somalia, I took a job as a radio reporter for ABC news. It wasn’t someplace I could go by myself. News organizations had to create fortresses for themselves in Mogadishu and man those forts with armies.

ABC sent in its most experienced fixers, men known in the news business (and not without respect) as “combat accountants.” The accountants hired forty gunmen and found a large walled house that used to belong to an Arab ambassador. The house was almost intact and close to the ruins of the American embassy, which—the accountants hoped—would soon be occupied by U.S. Marines.

Satellite dishes, telephone uplinks, editing equipment, half a dozen generators, fuel, food, water, beer, toilet paper, soap, sheets, towels, and mattresses all had to be flown in on charter planes from Nairobi. For some reason we wound up with five hundred boxes of a Kenyan chocolate chip cookie that tasted like bunion pads. Cooks, cleaning people, and laundry men were employed, as well as translators—dazed-looking academic types from the long-destroyed Somali National University.

Some thirty of us—journalists, camera crews, editors, producers, money men, and technicians—were housed in this compound, bedded down in shifts on the floor of the old audience hall while our mercenaries camped in the courtyard.

It was impossible to go outside our walls without “security” (“security” being what the Somali gunmen—gunboys, really—liked to be called). Even with the gunmen along, there were always people mobbing up to importune or gape. Hands tugging at wallet pockets. Fingers nipping at wristwatch bands. No foreigner could make a move without setting off a bee’s nest of attention—demanding, grasping, pushing crowds of cursing, whining, sneering people with more and worse Somalis skulking on the fringes of the pack.

One of the first things I saw, besides guns, when I arrived in Mogadishu was a pack of thieves creeping through the wreckage of the airport, sizing up our charter cargo. And the last thing I saw as I left was the self-appointed Somali “ground crew” running beside our taxiing plane, jamming their hands through the window hatch, trying to grab money from the pilot.

A trip from our compound to Mogadishu’s main market required two kids with AK-47s plus a driver and a translator who were usually armed as well. The market was walking distance but you wanted a car or truck to show your status. That there was a market at all in Mogadishu was testimony to something in the human spirit, though not necessarily something nice, since what was for sale was mostly food that had been donated to Somalia’s famine victims, CONTRIBUÉ PAR LES ENFANTS DE FRANCE said the stenciled letters on all the rice sacks. (Every French school child had been urged to bring to class a kilo of rice for Somalia.)

Meat was also available, though not immediately recognizable as such. A side of beef looked like fifty pounds of flies on a hook. And milk, being carried around in wooden jugs in the hundred-degree heat, had a smell that was worse than the look of the meat. But all of life’s staples, in some more or less awful form, were there in the market. If you had the money to get them. That is, if you had a gun to get the money. And a whole section of the market was devoted to retailing guns.

I wanted to buy a basket or something, just to see how the ordinary aspects of life worked in Somalia in the midst of total anarchy and also, frankly, to see if having my own gunmen was any help in price haggling. I was thinking I could get used to a pair of guys with AKs, one clearing a path for me and one covering my back. I’d be less worried about crime in the States, not to mention asking for a raise. And, if I happened to decide to go to a shrink, I’ll bet it would be remarkable how fast my emotions would mature, how quickly my insights would grow, how soon I’d be declared absolutely cured with two glowering Somali teens and their automatic weapons beside me on the couch.

They were, however, useless at bargaining for baskets. Nobody gets the best of a Somali market woman. Not only did the basket weaver soak me, but fifteen minutes after the deal had been concluded she chased me halfway across the marketplace screaming that she’d changed her mind. My bodyguards cringed and I gave up another three dollars—a sort of Third World adjustable basket mortgage.

She was a frightening lady. Ugly, too, though this was an exception. Somali women are mainly beautiful: tall, fine-featured, and thin even in fatter times than these. They are not overbothered with Muslim prudery. Their bright-colored scarves are used only for shade and not to cover elaborate cornrows and amazing smiles. Loud cotton print sarongs are worn with one shoulder bare and wrapped with purposeful imperfection of concealment. There is an Iman doppelgänger carrying every milk jug.

The model Iman is the widow of David Bowie, who died ten years ago this month.

You could do terrific business with modeling agencies hiring these girls by the pound in Somalia and renting them by the yard in New York.

The men, perhaps because I am one, are another matter. They’re cleaver-faced and jumpy and given to mirthless grins decorated with the dribble from endless chewing of qat leaves. Some wear the traditional tobe kilt. Others dress in Mork and Mindy–era American leisure wear. The old clothes that you give to charity are sold in bulk to dealers and wind up mostly in Africa. If you want to do something for the dignity of the people in sub–Saharan countries, you can quit donating bell-bottom pants to Goodwill.

When we emerged from the market our driver was standing next to the car with a look on his face like you or I might have if we’d gotten a parking ticket just seconds before we made it to the meter with the dime. Shards of glass were all over the front seat. The driver had been sitting behind the wheel when a spent bullet had come out of somewhere and shattered the window beside his head.

Mogadishu is almost on the equator. The sun sets at six, prompt. After that, unless we wanted to mount a reconnaissance in force, we were stuck inside our walls. We ate well. We had our canned goods from Kenya, and the Somalis baked us fresh bread (made from famine-relief flour, no doubt) and served us a hot meal every night—fresh vegetables, stuffed peppers, pasta, lobsters caught in the Mogadishu harbor and local beef. I tried not to think about the beef. Only a few of us got sick. We had a little bit of whiskey, lots of cigarettes, and the pain pills from the medical kits. We sat out on the flat tile roof of the big stucco house and listened to the intermittent artillery and small-arms fire.

Down in the courtyard our gunmen and drivers were chewing qat. The plant looks like watercress and tastes like a handful of something pulled at random from the flower garden. You have to chew a lot of it, a bundle the size of a whisk broom, and you have to chew it for a long time. It made my mouth numb and gave me a little bit of a stomachache, that’s all. Maybe qat is very subtle. I remember thinking cocaine was subtle, too, until I noticed I’d been awake for three weeks and didn’t know any of the naked people passed out around me. The Somalis seemed to get off. They start chewing before lunch but the high didn’t kick in until about three in the afternoon. Suddenly our drivers would start to drive straight into potholes at full speed. Straight into pedestrians and livestock, too. We called it “the qat hour.” The gunmen would all begin talking at once, and the chatter would increase in speed, volume, and intensity until, by dusk, frantic arguments and violent gesticulations had broken out all over the compound. That was when one of the combat accountants would have to go outside and give everybody his daily pay in big stacks of dirty Somali shilling notes worth four thousand to the dollar. Then the yelling really started.

Qat is grown in Kenya. “The Somalis can chew twenty planes a day!” said a woman who worked in the Nairobi airport. According to the Kenyan charter pilots some twenty loads of qat are indeed flown into Mogadishu each morning. Payloads are normally about a ton per flight. Qat is sold by the bunch, called a maduf, which retails for $3.75 and weighs about half a pound. Thus $300,000 worth of qat arrives in Somalia every day. But it takes U.S. Marines to deliver a sack of wheat. …

… Where did this strange nation come from? The Somalis have a joke: God was bored. So He created the universe. But that was boring, too. So God created Adam and Eve. But He was still bored. So God created the rest of the human race. And even then He was bored. So God created the Somalis. He hasn’t stopped laughing since.

As with all nomads, Somalis come basically from nowhere. Roving, quarreling, pillaging bands of Somalis show up in the Horn of Africa—the biblical land of Punt—about the same time that roving, quarreling, pillaging bands of Normans show up for the Battle of Hastings. The Somalis are, and seemingly always have been, divided into clan families. There are six of these: Dir, Isaaq, Hawiye, Darod, Digil, and Rahanweyn. They hate each other. Not that those are their only hatreds. The two worst Somali warlords extant at the time of my visit, Mohammed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Muhammad, were both Hawiye. Each clan family is divided into numerous subclans. They hate each other, too. And each subclan is likewise split and irked. The first Europeans, visiting Mogadishu in the sixteenth century, found the then-tiny city already riven into warring clan sectors.

Back when one culture could say what it thought of another without risking a massive Donna Shalala explosion, the 1911 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (the only reference work I really trust) opined, “The Somali are a fighting race and all go armed. … They are great talkers, keenly sensitive to ridicule, and quick tempered … love display … are inordinately vain and avaricious. …” And, said Britannica, “The Somali have very little political or social cohesion.” In fact, the basic unit of Somali society is something called the “diyapaying group,” diya being the Arabic word for blood money.

Besides the members of the six clan families, there are other nonclan Somalis known as sab, or “low.” These are hunters, barbers, leather-workers, metalsmiths, and other productive citizens much looked down upon by nomads. Noble camel thieves think sab vocations are degrading. The six clans themselves are divided in prestige according to degree of idleness. The Dir, Isaaq, Hawiye, and Darod call themselves “Samale,” from whence comes the name of the country. The Samale clans consider themselves to be strictly nomads—fighters and herdsmen. They call the Digil and the Rahanweyn “Sab clans,” and Rahanweyn, in Somali, means merely “large crowd.” The Sab are farmers, and nomads regard farms with the same violent distaste I have for law offices.

The gunmen who are currently destroying Somalia, who are wrecking the livelihoods of innocent Somalis and robbing them of their sustenance, are largely Samale. And many of the people who are starving are Sab. It is one of Somalia’s plentiful supply of grim ironies that the victims of its famine are the people who grow its food.

Of course the nomad clansmen doing the wrecking and robbing aren’t traditional nomads any more than a Toyota pickup truck with a machine gun mounted in its bed is a traditional element of a caravan. But the Samale don’t need to go on any Robert Bly wildman weekends to get in touch with their inner warrior. Somali became a written language only in 1972. Just a few miles from the main towns you see itinerant families of Darod and Dir who could pass for Mary and Joseph on their flight into Egypt. Here all the men are dressed in tobe kilts, with sword-length daggers in the waistbands, and the women are wrapped in homespun instead of Kenyan chintz. The camel bridles, donkey blankets, pannier baskets, and milk jugs have been made by hand. The nomad life is possessed of almost as much honest, natural, rough-hewn folksiness as a New England crafts fair. Only the occasional flash of a bright yellow plastic wash bucket tells you what millennium you’re in.

I have a friend, Carlos Mavroleon, who works as a freelance TV reporter for ABC and who has spent a lot of time among nomads in the Muslim world. Carlos found a very good translator and went off with a minimum of security and baggage to the far parts of the Somali desert to talk to the real Samale. They were shy of strangers—given current events in Somalia, they’d be crazy if they weren’t—and it took Carlos several days of lolling around making gifts of tea and tobacco before the nomads would chat. Finally they invited him into their camp, and, when a suitable length of pleasantries had been exchanged, Carlos asked the nomads, “How has this war affected you?”

“Oh, the war is terrible!” they replied. And they told Carlos that just last week some goats had been stolen and a month before a valuable camel was lost. It was a very horrible war indeed. More goats might be lost at any time and only a couple of years ago a wife had been carried away.

Carlos said he didn’t realize for a while that the war the nomads were talking about was the war they had been conducting, time out of mind, with the next subclan down the wadi. “No, no, no,” said Carlos, “I mean the big war in Mogadishu.”

“Oh, that war,” said the nomads, and there were shrugs all around.

Carlos liked the Somalis. “Men in skirts killing each other over matters of clan,” he said. “People call it barbaric savagery. Add bagpipes and a golf course, and they call it Scotland.”

And, like good Scots Presbyterians, the Somalis can be religious fanatics when they feel like it. Sayyid Muhammad ’Abdille Hassan, known as the “Mad Mullah,” fought the British Empire to a standstill in northern Somalia

This is the part that wants to be independent Somaliland.

in the Dervish Wars of 1900 to 1920. The British were forced to withdraw to coastal garrisons, causing famine among the Somali clans who were not allied with the Mullah. An estimated one-third of the population of British Somaliland died during the Dervish Wars, a period that Somalis call “The Time of Eating Filth.”

The British never intended to rule Somalia but found themselves continually forced to intervene in Somali affairs to ensure the supply line to their strategic outpost at Aden. In the words of I. M. Lewis in his A History of Modern Somalia, “The problem of the future status of these areas was complicated; no one friendly or fully acceptable … seemed to want them.” And they still don’t. Various internationalist schemes were attempted, which is where Italian Somaliland came from. The Mad Mullah was unimpressed. During World War I he wrote a letter to the British Commissioner at Berbera:

You … have joined with all the peoples of the world, with wastrels, and with slaves, because you are so weak. But if you were strong you would have stood by yourself as we do, independent and free. It is a sign of your weakness, this alliance of yours with Somali, menials, and Arabs, and Sudanese, and Kaffirs, and Perverts, and Yemenis, and Nubians, and Indians, and Russians, and Americans, and Italians, and Serbians, and Portuguese, and Japanese, and Greeks, and cannibals, and Sikhs, and Banyans, and Moors, and Afgans, and Egyptians … it is because of your weakness that you have to solicit as does a prostitute.

Seventy-five years before the fact, Sayyid Muhammad was able to accurately predict the composition, effectiveness, and moral stature of today’s UN.

The Mullah is still revered in Somalia. And the day I arrived in Mogadishu a flyer was being distributed in the local mosques showing a servile Somali rolling out a carpet for a pair of armed men mounted tandem on a horse. One man was marked with a cross and the other with a Star of David. Two fighting men on one horse was the seal of the Knights Templars, a Christian military order formed in the twelfth century to fight Muslims in the crusades. Sense may be short in these parts, but memories are long.

VI

So here we were on another crusade, this time one of compassion (though Richard the Lionhearted thought his cause was compassionate too). Enormous stores of food aid were arriving in Mogadishu, food donated by international governments and by private charities. Armed convoys were being formed to deliver that food. It takes a lot of weapons to do good works (as Richard the Lionhearted could have told us). …

Much uglier jokes were available. About food, for instance. It was all over the place. In fourteen hours of travel the previous day, we’d never been out of sight of the stuff. The American sergeant yelling at the Somalis for trying to grocery-shop in a famine was wrong. Just as I’d been wrong about parched sands when I’d seen our bivouac area. The Shebeli river valley is wet and fecund and contains the richest farmland in Somalia. The road from Mogadishu traversed miles of corn and sorghum, the fields marked out with animal skulls set on stakes. (Scarecrows, maybe, or scarepeoples. I saw a human skeleton beside the pavement.) Even in the drier areas, away from the river, there were herds of cows and goats. We’d been carrying thousands of pounds of food relief through thousands of acres of food. …

VII

On New Year’s Eve I went with another convoy west a hundred miles to Baidoa, this time with U.S. Marines in the lead. …

We began to drink and think big thoughts. What the hell were we doing here? We thought that, for instance. And we thought, well, at least some little bit of good is being done in Somalia. The director of the Baidoa orphanage had told us only one child died in December. Before the marines came, the children were dying like … “Dying like flies” is not a simile you’d use in Somalia. The flies wax prosperous and lead full lives. Before the marines came, the children were dying like children. Would this last? No, we thought. Everything will slip back into chaos as soon as the marines are gone. But to do some good briefly is better than doing no good ever. Or is it always? Somalia was being flooded with food aid. The only way to overcome the problem of theft was to make food too cheap to be worth stealing. Rice was selling for ten cents a pound in Somalia, the cheapest rice in the world. But what, we thought, did that mean to the people with the fields of corn and sorghum and the herds of goats and cattle? Are those now worth nothing, too? Had we come to a Somalia where some people sometimes starved only to leave a Somalia where everybody always would?

We had some more to drink and smoked as many cigars and cigarettes as we could to keep the mosquitoes away—mosquitoes which carry yellow fever, dengue, lymphatic filariasis, and four kinds of malaria, one of which is almost instantly fatal. Was this the worst place we’d ever covered? We thought it was. We had, among the four of us, nearly forty years’ experience of journalism in wretched spots. But Somalia … tiresome discomfort, irritating danger, amazing dirt, prolific disease, humdrum scenery (not counting this night sky), ugly food (especially the MREs we were chewing), rum weather, bum natives, and, everywhere you looked, suffering innocents and thriving swine. True, the women were beautiful, but all their fathers, brothers, uncles, husbands, and, for that matter, male children over twelve were armed.

Still, we thought, this wasn’t the worst New Year’s Eve we’d ever spent. We had a couple more drinks. We certainly weren’t worried about ecological ruin, shrinking white-collar job market, or fear of intimacy. All that “modern era anomie” disappears with a dose of Somalia. Fear cures anxiety. The genuinely alien banishes alienation. It’s hard for existential despair to flourish where actual existence is being snuffed out at every turn. Real Schmerz trumps Weltschmerz. If you have enough to drink.

But what do you do about Somalia? We had even more to drink and reasoned as hard as we could.

Professor Amartya Sen says, “There has never been a famine in any country that’s been a democracy with a relatively free press. I know of no exception. It applies to very poor countries with democratic systems as well as to rich ones.”

And in the New York Times article featuring that quote from Professor Sen, Sylvia Nasar says, “Modern transportation has made it easy to move relief supplies. But far more important are the incentives governments have to save their own people. It’s no accident that the familiar horror stories … occurred in one-party states, dictatorships or colonies: China, British India, Stalin’s Russia.” She notes that India has had no famine since independence even though the country suffered severe food shortages in 1967, 1973, 1979, and 1987.

Says Professor Sen, “My point really is that if famine is about to develop, democracy can guarantee that it won’t.” And he goes on to say that when there is no free press “it’s amazing how ignorant and immune from pressure the government can be.”

Well, for the moment at least, Somalia certainly had a free press. The four of us were so free nobody even knew where we were. But how do you get Somalia one of those democratic systems Amartya Sen is so fond of? How, indeed, do you get it any system at all? Provisional government by clan elders? Permanent international occupation? UN Trusteeship? Neo-colonialism? Sell the place to Microsoft? Or … Or … Or …

We were deep into the second bottle of scotch now, and boozy frustration was rising in our gorges along with the MRE entrées. It’s all well and good to talk about what can be done to end famine in general. But what can be done about famine specifically? About this famine in particular? About a place as screwed-up as Somalia? What the fucking goddamn hell do you do?

There’s one ugly thought that has occurred to almost everyone who’s been to Somalia. I heard a marine private in the Baidoa convoy put it succinctly. He said, “Somalis—give them better arms and training and seal the borders.”

I had a personal interaction with PJ. I asked him to blurb a book, thinking, You're out of your mind. He gets a hundred requests like this every month. I've never seen an author of his stature be so gracious. He was defiant. “I owe the universe a favor,” he said. “People were good to me as a young author, I hope I do them justice.”

That man can sure turn a phrase.